What is moving will be still

What is gathered will disperse

What has been built up will collapse

Andrew Bird, “Tin Foil” (Fingerlings 3, 2006)

These lyrics are an adapted quote from Lama Sogyal Rinpoche’s Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. Impermanence (aniccā in Pali) is an important idea in many forms of Buddhism. It is one of the three marks of existence, along with non-existence of self-essence (anattā) and suffering (dukkha). Similar concepts exist in existentialism and related philosophies.

Nietzsche provides an example of why impermanence is also important for western philosophy:

Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of “world history,” but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die. One might invent such a fable, and yet he still would not have adequately illustrated how miserable, how shadowy and transient, how aimless and arbitrary the human intellect looks within nature. There were eternities during which it did not exist. And when it is all over with the human intellect, nothing will have happened. For this intellect has no additional mission which would lead it beyond human life. Rather, it is human, and only its possessor and begetter takes it so solemnly-as though the world’s axis turned within it. But if we could communicate with the gnat, we would learn that he likewise flies through the air with the same solemnity, that he feels the flying center of the universe within himself.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense (1873)

Religious leaders were somewhat right to fear the idea of heliocentrism and the revelations of the true scale of the universe’s size and age. Humans appear worryingly insignificant in the face of countless galaxies, but our minuscule size is at least relatively salient: we can look at the night sky and experience a vague but profound feeling of smallness. On the other hand, the insignificance of the whole of human history (and almost certainly the whole of humanity’s future) relative to the age of the universe is not always so apparent to us. That is not to mention the future of the universe, which could last for hundreds of trillions of years, if not a literal eternity. The actions of a single human may have consequences long after their death, but probably no longer than the lifespan of the sun. To the extent that consequences determine the importance of an event, all human action is ultimately unimportant. At some point in the future, there will no longer be an appreciable difference between a person having done a thing or not having done the thing.

If our existence is contingent and our annihilation is assured, then what really matters and what are we to do with our lives?

Camus labeled this disconnect between our desired importance and our actual importance absurd. It is absurd that humans search for meaning and purpose in our lives when there is no such meaning or purpose to be found. This is the “problem” of existential nihilism.

If in order to elude the anxious question: “What would life be?” one must, like the donkey, feed on the roses of illusion, then the absurd mind, rather than resigning itself to falsehood, prefers to adopt fearlessly Kierkegaard’ s reply: “despair.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942)

Camus implores us not to lie to ourselves about the meaning of life, but the alternative is not always easy. Sartre provides an example of self-deception in action:

Let us consider this waiter in the cafe. His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tight-rope-walker by putting it in a perpetually unstable, perpetually broken equilibrium which he perpetually re-establishes by a light movement of the arm and hand. All his behavior seems to be a game. He applies himself to chaining his movements as they were mechanisms, the one regulating the other; his gestures and even his voice seem to be mechanisms; he gives himself the quickness and pitiless rapidity of things. He is playing, he is amusing himself. But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it. He is playing at being a waiter in a cafe. … [Internally] the waiter in the cafe can not be immediately a cafe waiter in the sense that this inkwell is an inkwell, or the glass is a glass. It is by no means that he can not form reflective judgments or concepts concerning his condition. … [Speaking as the waiter:] What I attempt to realize is a being-in-itself of the cafe waiter, as if it were not just in my power to confer their value and their urgency upon my duties and the rights of my position, as if it were not my free choice to get up each morning at five o’clock or to remain in bed, even though it meant getting fired.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness (1943)

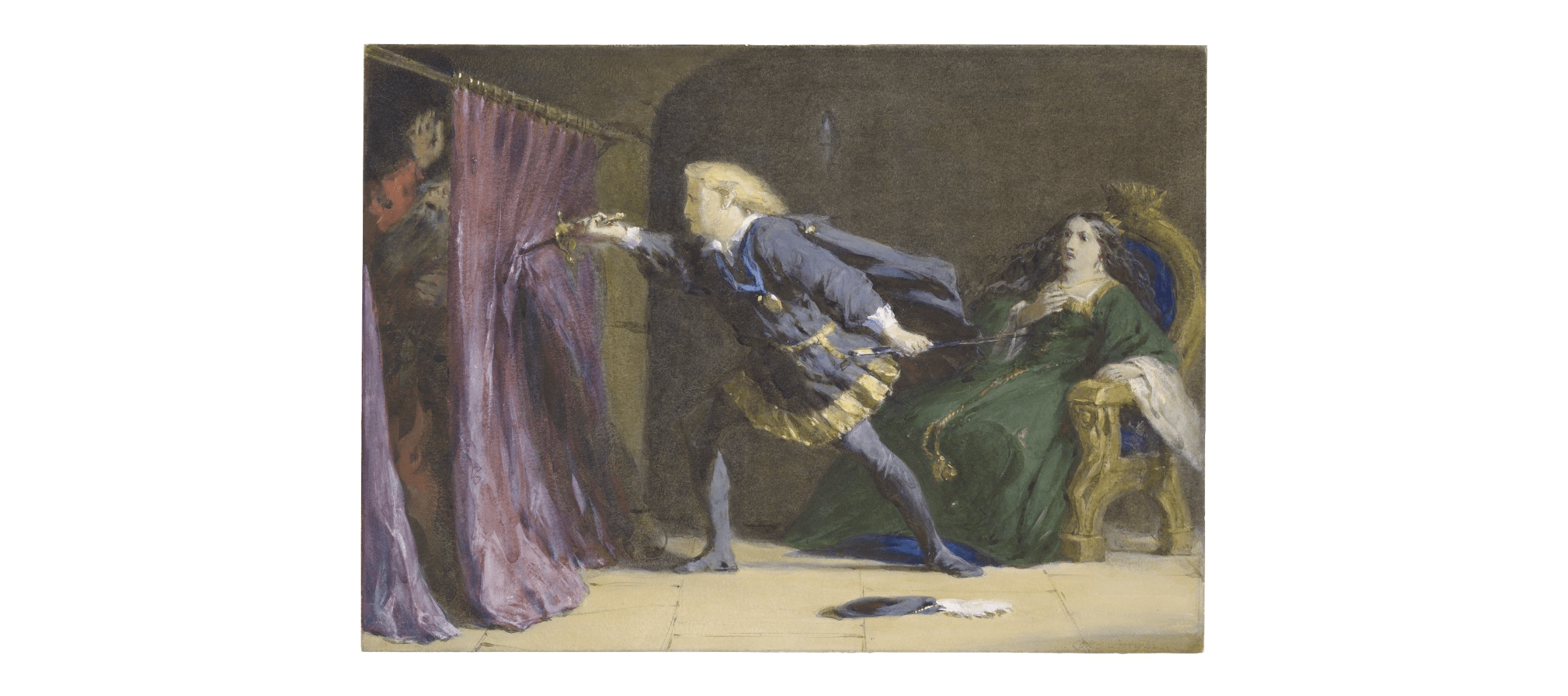

As Sartre says, the waiter is no more a waiter than the actor playing Hamlet is Hamlet. The character of Hamlet has his destiny laid out for him. He must kill Polonius; that is what Hamlet does. That is part of his purpose in the plot. The waiter imagines that his destiny is that of a waiter: he must take orders and deliver food and so on. That is the purpose of the waiter. But the actor is not Hamlet. He may choose to disrupt the play by pulling back the curtain and revealing Polonius instead of killing him. Likewise, the man serving in the cafe is not a waiter. A waiter cannot stay in bed, for he would no longer be a waiter, but the man may choose to do so, since he never really was a waiter– he was only pretending.

Humans are thrown into the world without any purpose defined for us, and this can lead to anguish and despair. In order to cope, we might imagine being something other than ourselves, something that does have a defined purpose. We would think, I am a waiter and I must do what a waiter must do, rather than, I have a job waiting tables and I choose to wait tables. If I am a waiter, my destiny is a waiter’s destiny. If I am myself, my future is uncertain and I am responsible for shaping it myself.

I was raised up believing I was somehow unique

Like a snowflake, distinct among snowflakes, unique in each way you can see

And now after some thinking, I’d say I’d rather be

A functioning cog in some great machinery serving something beyond me

Fleet Foxes, “Helplessness Blues” (Helplessness Blues, 2011)

Most religions are of relatively little help, in the sense that we cannot be rescued from the human condition. Sartre points out that our situation is fundamentally the same as having no God in this regard. We still have to choose to have faith in one religion or another. We still have to choose the meaning of our own lives. Kierkegaard was a Christian and Camus was an atheist, but they both acknowledged the same human condition. While the promise of an eternal afterlife can be reassuring, especially if it involves Judgment that makes choices during life important, our reality is still only the present moment. Here we are, alive and uncertain, with no choice but to make our own choices.

How do we avoid self-deception then?

For Camus, the answer is to embrace the absurd and become the “absurd hero” of our own lives. The act of living a meaningful life in a meaningless universe is an act of rebellion.

The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942)

For Sartre, the answer is living authentically as yourself. This means coming to grips with both our freedom and our responsibility to create our own meaning.

For Nietzsche, the answer is self-overcoming. We must seize existence for ourselves.

We must face reality, and suffering is part of life. It is not to be eliminated, it is to be overcome, leading to growth. We make everything around us so easy, superficial, and bright, unable to face reality. Is this truly freedom? For Nietzsche, this is a simplified and falsified world. So, to delight in life itself, we must confront it at face value – everything evil, terrible, and snakelike in humanity serves just as well as its opposite to enhance the species “humanity”. We are to be grateful for even difficulties.

Eternalised, “Nietzsche on Self-Overcoming” (2020)

We cannot not avoid despair. We must instead fearlessly choose despair.

Life is giving me trash and I’m just going to embrace it, like a raccoon. Bet you didn’t expect that, Life.

Anne the Pancake, “Memes: Language of the absurd” (2023)

Our anxieties will never be assuaged by pretending things are other than they are. The alternative, then, is to shed the false limitations we place on ourselves and live a life of joy and fulfillment while willingly experiencing despair, anguish, anxiety, grief, and anger. Do not live for the nonexistent impact you will (not) have on the universe’s distant future, live for yourself as you are right now. We are each powerfully free to choose our own path.

In his heart every man knows quite well that, being unique, he will be in the world only once and that no imaginable chance will for a second time gather together into a unity so strangely variegated an assortment as he is: he knows it but he hides it like a bad conscience—why? From fear of his neighbor, who demands conventionality and cloaks himself with it.

…No one can construct for you the bridge upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Schopenhauer as Educator (1874)

Life’s a game, life’s a joke

Fuck it

Why not go for broke?

Trade in all your chips

and learn how to be free

Why abstain? Why jump in line?

We’re all living on borrowed time

So do what you like

and they’ll like what you do when you do it

And if they don’t that’s fine

Fuck ’em!

Days N’ Daze, “Fuck It!” (Rogue Taxidermy, 2013)

Recommended further reading: How Buddhism resolves the paradox of self-deception by Katie Javanaud (2019)