In Part 1, we looked at the early development of writing, the spread of different scripts, and the historical example of ancient Egyptian. In Part 2, we’ll look at a modern example of written language, some scripts that were invented in unusual ways, and how writing has been used as an art form.

The history of a peculiar modern language

Modern Japanese has one of the most complex writing systems in the world and is widely regarded as one of the most difficult writing systems to learn. The Japanese language itself is part of the Japonic family, a small and isolated language family. Japanese was first written in Chinese characters, despite the fact that the Chinese language is in the Sino-Tibetan family and not closely related to Japanese.

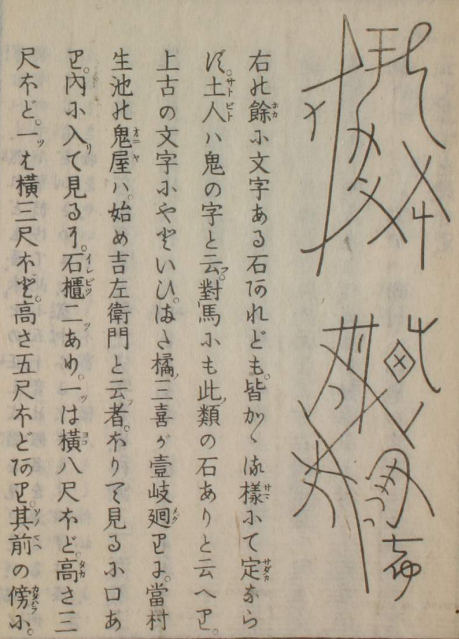

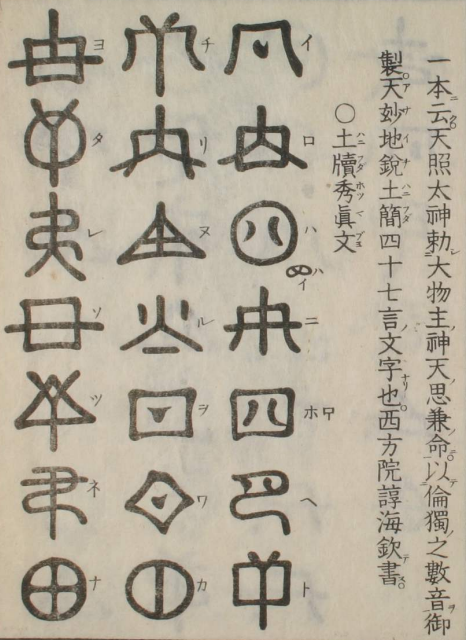

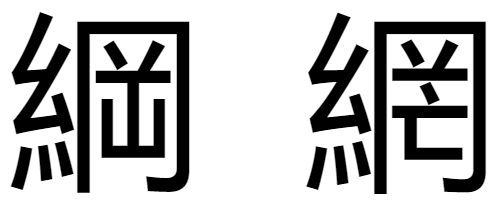

Below are excerpts from the book Shinji Nichibunden (神字日文伝), c. 1819 CE showing various jindai moji or kamiyo moji– “ancient characters” or “spirit script.” These scripts were thought by some to precede the use of Chinese characters, and also thought by some to be created or used by gods or spirits, but all such scripts are thought today to be fabrications. (One) motivation for the creation of these scripts was nationalism and animosity towards China. Japanese nationalists during the Edo period believed it would make Japanese culture look superior if they created their own writing system from nothing. However, the development of the Japanese writing system from Chinese took possibly even greater ingenuity.

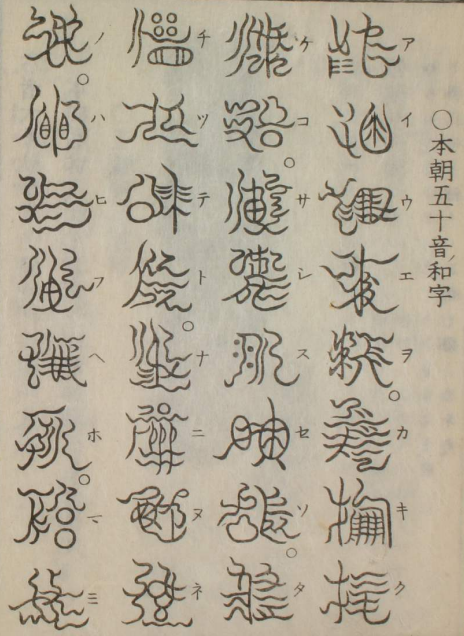

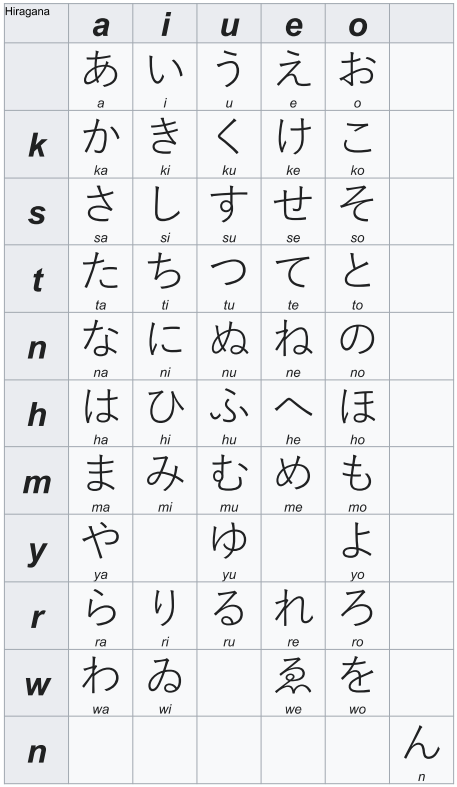

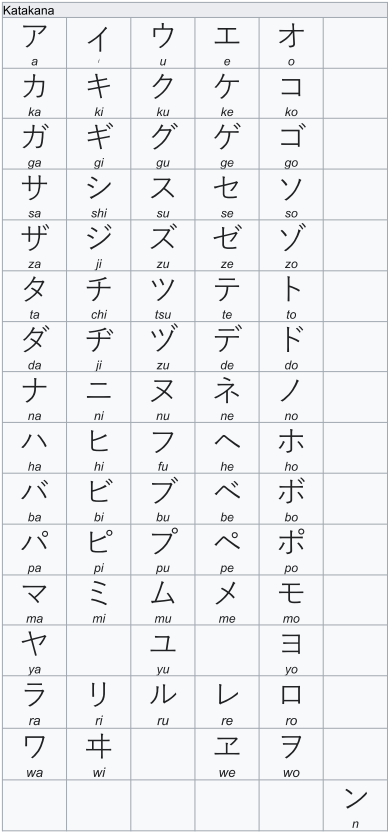

In order for Japanese to utilize Chinese characters, they had to be adapted to the needs of the Japanese language. In modern Japanese, there are three main writing systems that work together, kanji, hiragana, and katakana. Japanese has no alphabet, but it has two syllabaries, hiragana and katakana, collectively referred to as kana. Hiragana is normally used for native Japanese words, and katakana is typically used for loan words, foreign names, etc. Katakana includes sounds less often found in Japanese.

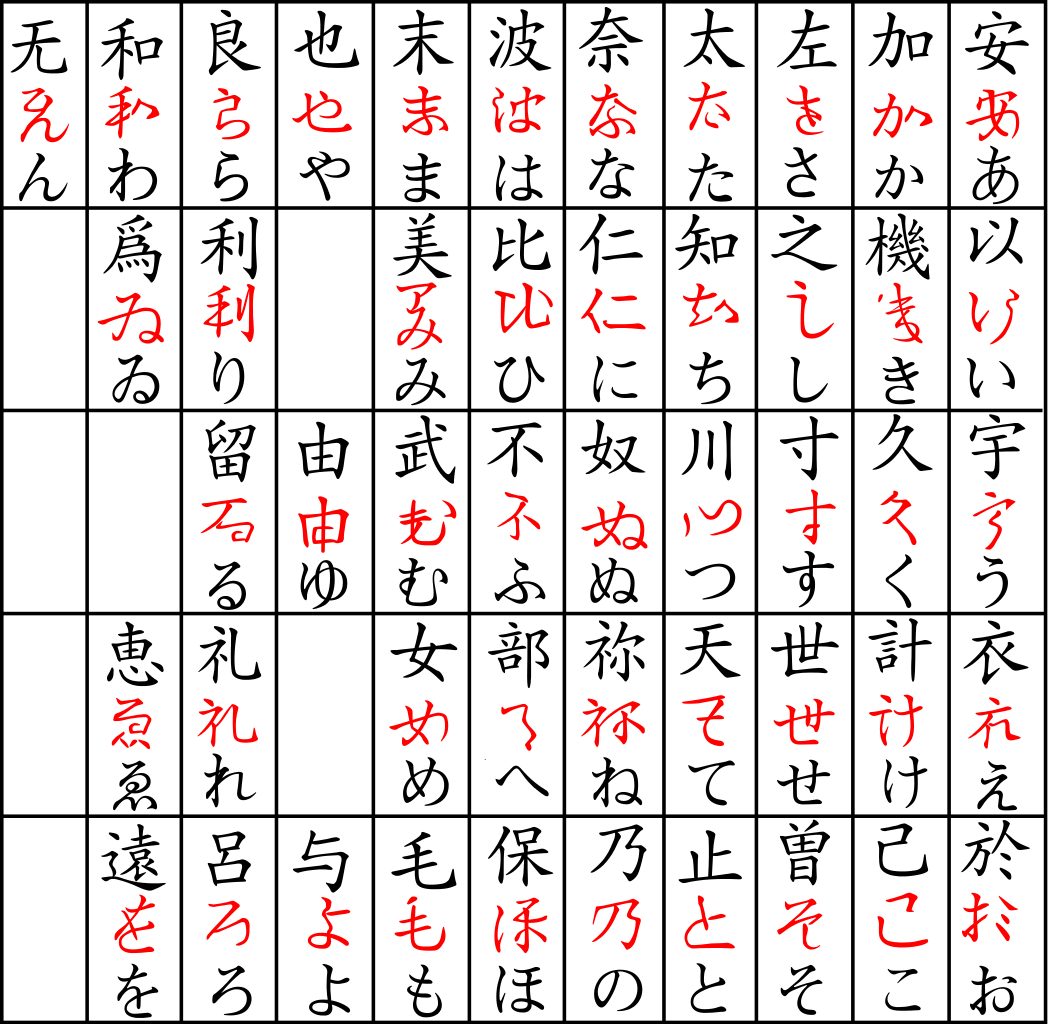

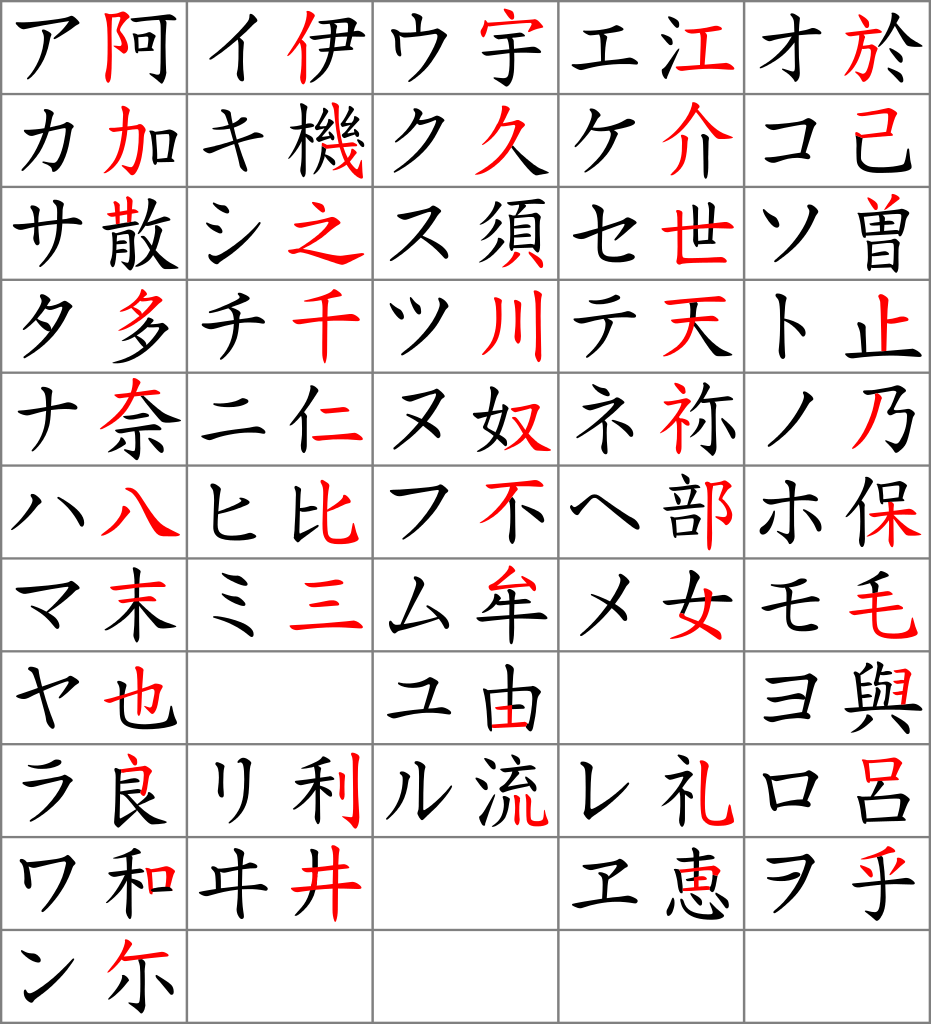

The derivations of kana from Chinese characters is shown below. Hiragana are essentially simplified cursive versions of the characters, while katakana are components extracted from characters.

One thing we may notice looking at the kana is that using syllables as phonetic units reduces the number of possible combinations. (Technically, kana characters do not represent syllables, but rather each character represents a mora. A mora is a unit of phonological timing.) Obviously, languages never exhaust their supply of words in this sense of running out of unique combinations of letters, and there is no language that has a word like *dddd. However, the principle being illustrated here may still apply: Japanese has a large number of homophones, words that are pronounced the same and spelled the same phonetically in kana. Japanese has a few ways of dealing with this. For one, spoken Japanese has a tonal component. In Japanese hashi can mean either “bridge” or “chopsticks,” but the two words are not pronounced the same. “Chopsticks” is háshi, with accent placed on the first mora (/HA-shi/). “Bridge” is hashí, with accent placed on the second mora (/ha-SHI/). Note that these are spelled the same when written phonetically in hiragana: はし; however, in written Japanese, homophones can be distinguished by their spelling in kanji. (See Smith, 1996, p. 210.)

Kanji appear at first glance to be logograms formed from Chinese characters. In some cases, it is this simple. The kanji character 草 represents the word kusa (“grass”). In Chinese, 草 also means “grass,” although the word is pronounced completely differently. Kanji can be more complicated, however. A character can have multiple different readings, an on-reading or a kun-reading. When this phenomenon collides with the existence of homophones with different kanji representations, we get a network of words that are related by being either homophones or homographs. A part of that network is illustrated below. This isn’t very important as far as I know, but it is interesting. This is the basis of some Japanese puns and wordplay.

When considering entire phrases, it gets even more complicated.

Here is an example of how complex the problem is. Let us say take the phrase Hi no sasanai yashiki (A Mansion with no Sunshine), which could be the name of a novel or a film. Here are twelve legitimate ways (some more likely than others) of how to write this.

- 日の差さない屋敷

- 日の射さない屋敷

- 日のささない屋敷

- 日の射さない邸

- 日の差さない邸

- 日のささない邸

- 陽の射さない屋敷

- 陽の差さない屋敷

- 陽のささない屋敷

- 陽の射さない邸

- 陽の差さない邸

- 陽のささない邸

We did a survey on six native Japanese speakers, some of whom are professional translators and writers, asking them how they would write the above phrase. Surprisingly, we received six different answers, none of which matched the “standard” form found in dictionaries (#1 above).

Jack Halpern (2001), “The Complexities of Japanese Homophones”

There are about 2,000 kanji characters in common use in modern Japanese. The comprehensive dictionary Daikanwa Jiten, which includes specialist terms and historical words, contains about 50,000 characters. Some Japanese words are compound, spelled with multiple kanji characters.

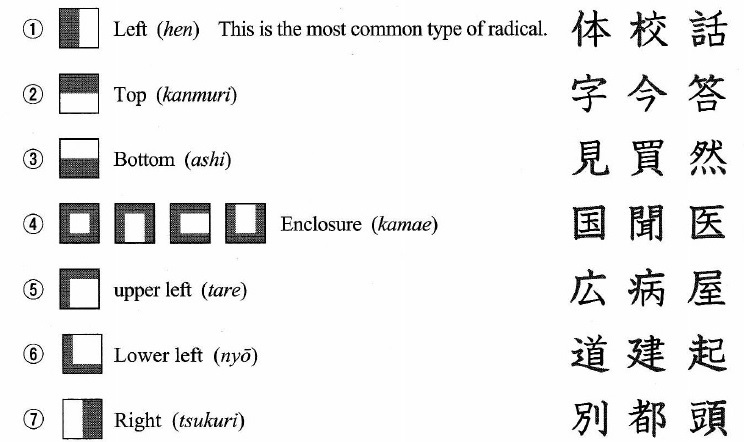

Kanji characters themselves are complex. The most key component of a kanji character is its radical. Radicals provide a way of categorizing characters and is how characters can be looked up in dictionaries (characters and radicals are both sorted by number of strokes it takes to write). There are 214 radicals in total, but around 50 of these cover the majority of everyday words. In some cases, the radical can offer a clue to the meaning and/or pronunciation of a kanji character.

(See Kess 2005)

Compounding the difficulty of reading kanji is the fact that some characters look very similar:

(See 20 Similar-Looking Kanji)

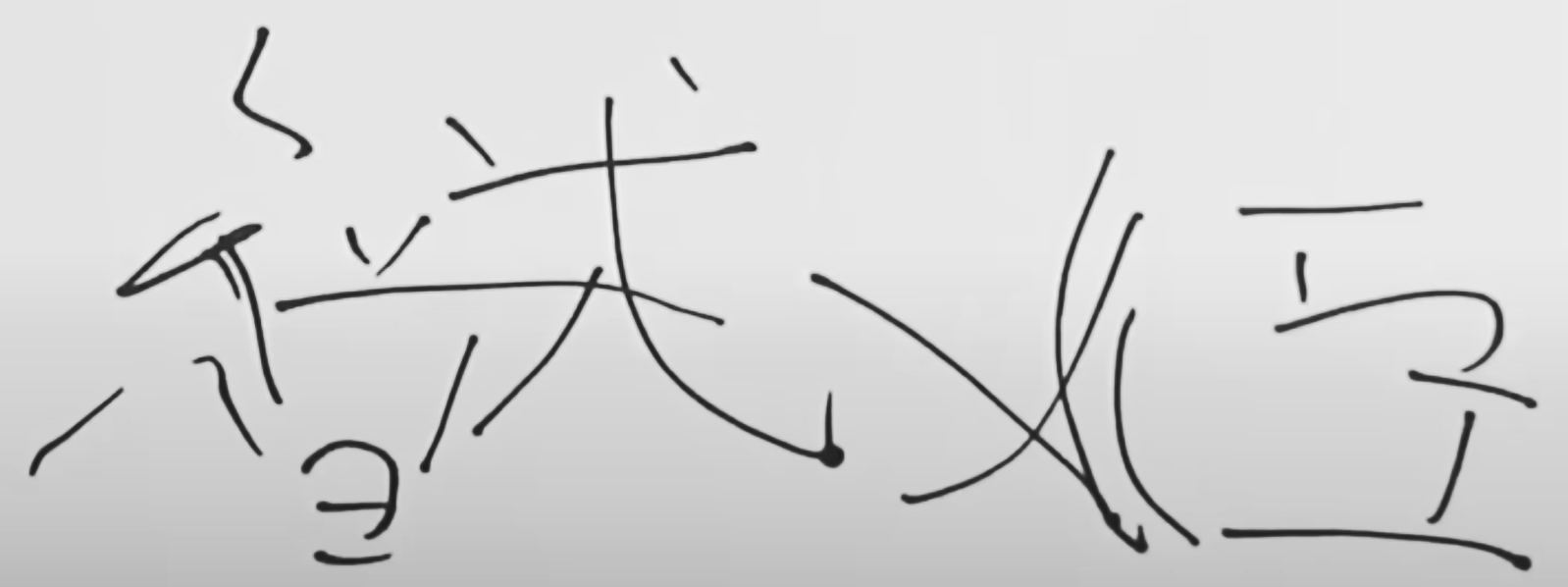

One thing that is difficult for some people learning to write Japanese is the fact that stroke order matters. While Latin letters have standard ways of being written, it tends to matter less in English if someone has an idiosyncratic way of forming letters. However, predefined stroke order has a number of advantages. I encountered an interesting example of this in virtual YouTuber Sakamata Chloe. Chloe has notoriously poor handwriting, and other people have a lot of trouble reading it. In some cases, Chloe herself can’t tell what she wrote. In one stream, she showed her hands writing out characters and asked the audience to guess the word she had written. According to several commenters, it was easy for them to decipher her writing when they were able to see her writing it because they saw the order in which she made the strokes. In other words, the end result is virtually unreadable, but the stroke order gives a massive clue as to what character was written.

When it comes to reading kanji, the characters must be memorized. Unlike English, if you don’t know a word written in kanji you cannot “sound it out.” For that reason, written Japanese incorporates a distinctive technology. This technology is furigana, and consists of writing a word phonetically in kana above a kanji character. The use of furigana varies by text and especially by audience. A comic book for small children might use furigana even for relatively common words, while subtitles on a news program might use furigana only for uncommon words. Furigana can also indicate which reading of a kanji character is appropriate.

There are many other ways furigana can be used. These are nice examples of the creative utilization of existing tools within a language by its speakers (or writers, in this case). For one, furigana can be used to provide a Japanese translation of a foreign word or phrase.

Since in cases like the one above the furigana may contain kanji, it is also possible (though rare) to have furigana on furigana.

(See Furigana | Japanese with Anime)

Invented writing systems

As mentioned in Part 1, the Hangul script for the Korean language was deliberately invented, as opposed to developing organically over a long time. There are several examples of this in history. For some languages that did not previously have writing systems, a script was invented by an outsider (often a colonizer, missionary, and/or anthropologist). However, many writing systems were invented by a native speaker of the language, sometimes to replace a less appropriate writing system (as in the case of Korean which had been using Chinese characters).

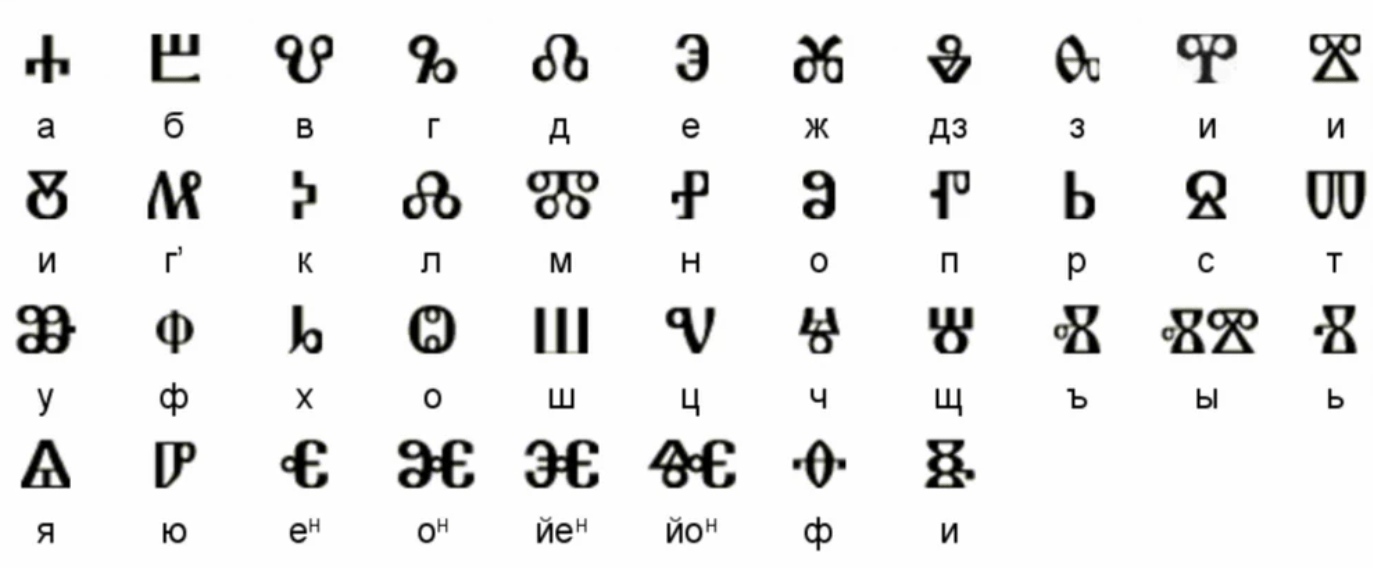

Cyrillic

The Cyrillic alphabet is a notable example of an invented writing system. In the 9th century CE, brothers Cyril and Methodius from the Byzantine Empire were Christian missionaries to the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe. In order to spread their religious teachings to the illiterate Slavs, they devised a writing system for local Slavic languages called the Glagolitic script. This alphabet was based partially on Greek. Cyril and Methodius established schools, and their students developed a streamlined version of the script. Though not invented by Cyril himself, the new script was named Cyrillic after him.

Cyril and Methodius were born as Constantine and Michael, respectively. They lived not long before the Great East-West Schism of 1054 which permanently separated the Catholic (western) Church from the Orthodox (eastern) Church. Christianity was widespread in much of Europe and the Church held political power, however internal theological disagreements tended to cause conflict and divide Christians into (usually regional) factions.

The Germanic people of East Francia (a remnant of Charlemagne’s empire) shared a border with the Slavs. Though Christian, they disapproved of Cyril and Methodius preaching to the Slavs in their own language. Cyril and Methodius were arrested for heresy but were released on the pope’s orders.

… they began to teach the services in the Slavic language. This aroused the malice of the German bishops, who celebrated divine services in the Moravian churches in Latin. They rose up against the holy brothers, convinced that divine services must be done in one of three languages: Hebrew, Greek or Latin.

Orthodox Church in America (2001)

The two brothers are alleged to have performed miracles after they died, and are venerated as saints. They are regarded most highly by the Eastern Orthodox Church, which refers to them as “equals of the apostles.”

The Cherokee syllabary

The writing system for the Cherokee (Tsagali) language was invented by Sequoyah in the early 19th century CE. This is a rare example of an illiterate member of a language community creating a writing system for their language essentially from scratch, and one of the only examples in which such a writing system has been widely adopted. Sequoyah’s system is a syllabary, similar to Japanese kana.

While the shapes of the symbols are similar (or identical) to letters in the Latin, Cyrillic, Glagolitic, and Greek alphabets, their visual appearance is the only connection.

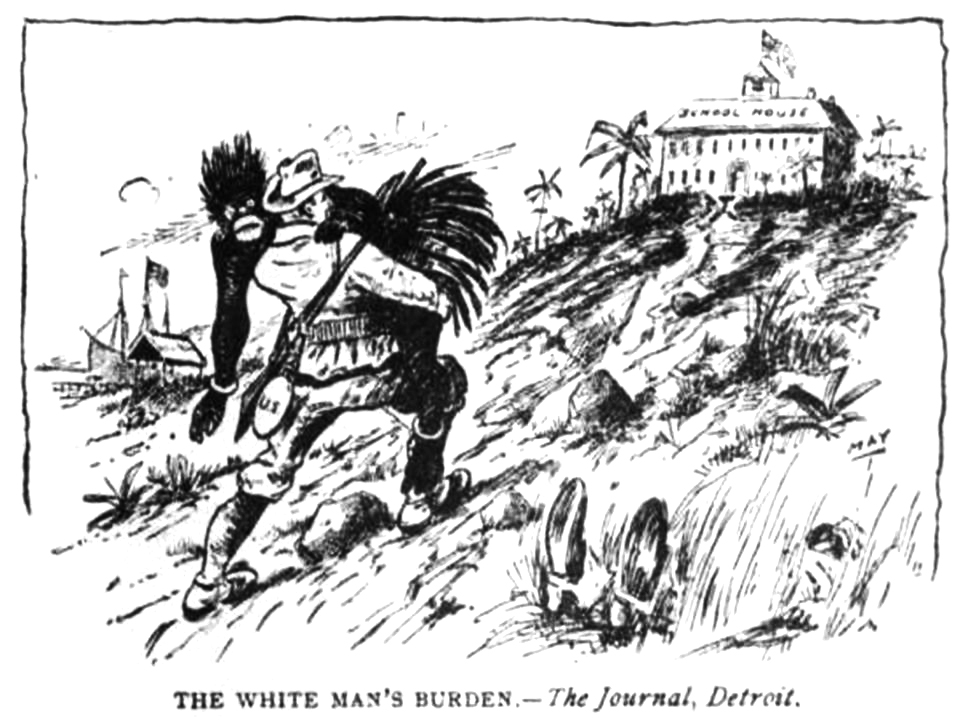

Cherokee is an endangered language with estimated less than 2,000 speakers (Scott Mckie B.P., 2019) and no young people speaking it as their first language. It is a member of the Iroquoian language family, all of the members of which are endangered or extinct. (See Iroquian | Ethnologue.) Most of this is a result of a concerted effort by colonizers to eradicate these languages in order to “civilize” the native speakers. This campaign ended only recently, thanks not to white benevolence but rather to the success of Native people who have fought for recognition and civil rights.

For more than a century, Native children in North America were routinely kidnapped and sent to boarding schools. Many of these individuals later spoke and wrote in English about their experiences and advocated for Native rights.

Judéwin said: “Now the paleface is angry with us. She is going to punish us for falling into the snow. If she looks straight into your eyes and talks loudly, you must wait until she stops. Then, after a tiny pause, say, ‘No.'” The rest of the way we practiced upon the little word “no.”

As it happened, Thowin was summoned to judgment first. The door shut behind her with a click.

Judéwin and I stood silently listening at the keyhole. The paleface woman talked in very severe tones. Her words fell from her lips like crackling embers, and her inflection ran up like the small end of a switch. I understood her voice better than the things she was saying. I was certain we had made her very impatient with us. Judéwin heard enough of the words to realize all too late that she had taught us the wrong reply.

“Oh, poor Thowin!” she gasped, as she put both hands over her ears.

Just then I heard Thowin’s tremulous answer, “No.”

With an angry exclamation, the woman gave her a hard spanking. Then she stopped to say something. Judéwin said it was this: “Are you going to obey my word the next time?”

Thowin answered again with the only word at her command, “No.”

This time the woman meant her blows to smart, for the poor frightened girl shrieked at the top of her voice. In the midst of the whipping the blows ceased abruptly, and the woman asked another question: “Are you going to fall in the snow again?”

Thowin gave her bad password another trial. We heard her say feebly, “No! No!”

With this the woman hid away her half-worn slipper, and led the child out, stroking her black shorn head. Perhaps it occurred to her that brute force is not the solution for such a problem. She did nothing to Judéwin nor to me. She only returned to us our unhappy comrade, and left us alone in the room.

During the first two or three seasons misunderstandings as ridiculous as this one of the snow episode frequently took place, bringing unjustifiable frights and punishments into our little lives.

Zitkala-Ša, American Indian Stories (1921)

In the US, there was an official policy of termination, the total eradication of Native tribes as independent entities. While this is now recognized as genocidal, the perpetrators at the time believed they were being helpful. They came from a white supremacist culture. Moreover, the 18th and 19th centuries marked a time when Europeans believed they were enlightened with science and logic and political philosophy. Many believed in Native Americans’ inherent worth as humans, and that Natives could be assimilated into the Anglo-American culture.

Americanizing the Indian … is a regrettably patronizing phrase. After all, we were Americans before you were. What you are interested in is Europeanizing the original Americans. Many of us are willing to accept European ideas about science and public health, but most reluctant to accept European ideas about government.

Ruth Muskrat Bronson (1948), quoted in Philp (1999, p. 68)

Most recently, since around 2020, the Land Back (or #LandBack) movement has been working to restore Native sovereignty and language.

IT IS THE RECLAMATION OF EVERYTHING STOLEN FROM THE ORIGINAL PEOPLES:

The LandBack Manifesto (2021)

LAND, LANGUAGE, CEREMONY,

FOOD, EDUCATION, HOUSING,

HEALTHCARE, GOVERNANCE,

MEDICINES, KINSHIP

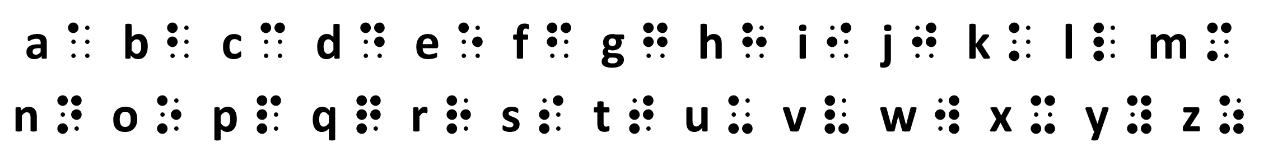

Braille

Braille is a tactile code designed to enable reading without the use of sight. It was invented by Louis Braille in 1821. Previously, a common approach was to use raised lettering, but such texts were difficult to produce and difficult to read. Braille was blinded at a young age, and first devised his code at the age of 12 after learning about the French military practice of “night writing.”

The original military code was called night writing and was used by soldiers to communicate after dark. It was based on a twelve-dot cell, two-dots wide by six-dots high. Each dot or combination of dots within the cell stood for a phonetic sound. The problem with the military code was that a single fingertip could not feel all the dots with one touch.

NLS Factsheet: About Braille (Library of Congress)

Braille initially encoded the Latin alphabet as used in French. In the following several decades, more symbols were added.

Although there are 64 possible combinations of 6 dots, many of them are unused (or rarely used) in order to reduce ambiguity and make it easier to quickly identify letters. For example, braille uses the 26 letters shown above, but in order to write the digits 0-9, braille only uses one additional letter. Instead of 10 distinct symbols, braille uses the symbols for the letters a-j with a “numeral” prefix indicating that we mean number instead of letter. (Note the numerals in braille go from 1-9 followed by 0.) Similarly, braille does not add 26 more letters to represent capitals, but rather includes a single “uppercase” prefix.

Because reading braille is generally slower than reading by sight, there is a greater need for abbreviations. Some common abbreviations have been standardized.

For languages that do not use the same 26-letter Latin alphabet, a different encoding scheme is necessary. An international standard was established for phonetic alphabets, so that letters roughly correspond across languages. For example, the Arabic ʾalif and the English a both use the same braille letter. Additional letters and diacritics require extra braille letters. China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan each have their own domestic braille standard. For Chinese logographic characters, words can be transliterated phonetically.

Writing as art

Calligraphy

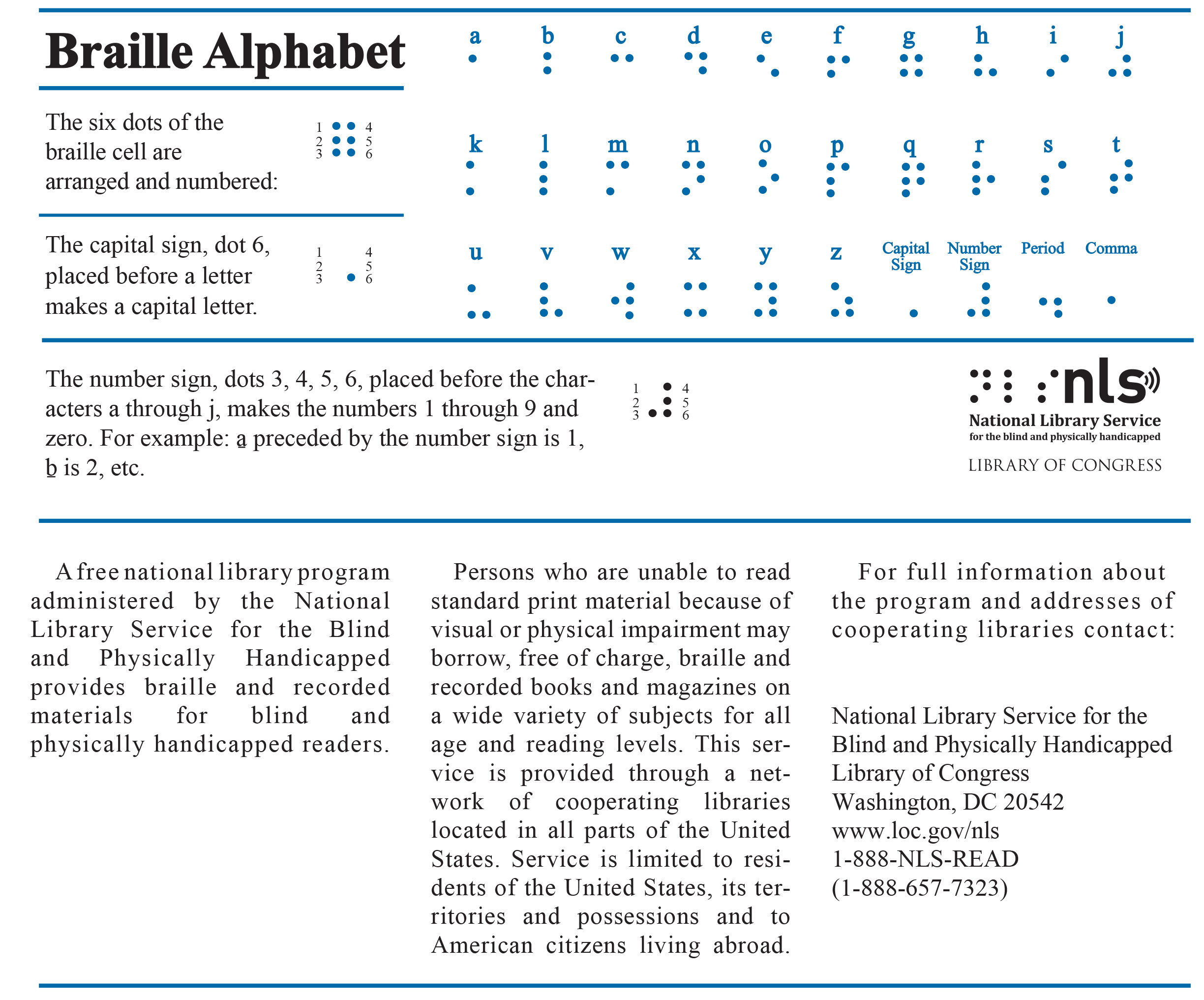

If art turned into writing through pictograms, then written symbols turned back into art through calligraphy. Calligraphy has a long history across many cultures and has served many different purposes. Calligraphy is frequently associated with some kind of religious or spiritual practice.

In Europe during the Middle Ages, Christian monks created intricately decorated illuminated manuscripts, featuring colorful illustrations and gold leaf. These manuscripts were typically Bibles or prayer books. The illumination was thought to exalt the text and glorify God. More concretely, the emotional response to such beautifully detailed artwork strengthens the religious feelings of the reader and makes the text more credible (see Viejo 2017). Illustrations also help the reader interpret the text, and can benefit even the illiterate (which was most Europeans at that time). Such manuscripts were usually written in Latin, but some contained Greek. After illuminated manuscripts became an established tradition, they started being produced by people other than monks and came to be lavish symbols of wealth and ostentatious religious devotion.

We see that animals are a common motif in artistic writings:

Calligraphy is particularly important in Islamic culture. Since the Qur’an was canonically revealed to the Prophet Mohammed in Arabic, the Arabic language has special status in Islam (Kamusela 2017). Additionally, many branches of Islam are aniconist, meaning they consider artistic depictions of sentient beings to be sacrilege (Ali 2022). These two features of Islam together created an environment in which calligraphy was an obvious choice for religious art.

The tradition of illuminated manuscripts was not limited to Christianity. European Jews during the Middle Ages also created illuminated manuscripts of important Jewish religious texts. These texts were written in Hebrew. Similar to Arabic in Islam (though for different reasons), the Hebrew language is important in the Jewish religion. Some forms of Jewish mysticism even view Hebrew letters as having magical properties (Paluch 2016).

Chinese calligraphy is one of the most well-known, ancient, and prolific calligraphic traditions. This tradition spread to other countries that used Chinese characters, including Korea and Japan. Calligraphy in this region is associated with Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, and many examples of calligraphy are poems, mantras, and aphorisms. The writing of calligraphy is itself considered a meditative practice.

(See Eubanks 2016)

Calligraphy, seen at first as just handwriting on paper, has little significance. But in truth, it is profoundly significant: it is the expression of one’s own life. Not all lines written with a brush can be called calligraphic lines. Calligraphic lines correspond to a formula, and contain strength, fluidity, and variation. Using high-quality strokes, calligraphers construct characters with diverse shapes, and think about the arrangement of the artistic parts with respect to the whole. A calligraphy work’s creation process cannot be repeated. All calligraphy strokes are permanent and immutable, demanding careful planning and confident execution, and involving many years of hard training. Different styles of writing and different forms of work form the Chinese calligraphy art. The spirit of Chinese art is the result of this Chinese “totality thinking.”

Qian and Fang 2007, p. 118

Graffiti

These scribblings have been said to provide a unique insight into society, because messages written through graffiti are often made without the social constraints that might otherwise limit free expression of political or controversial thoughts. … Archaeologists have also examined graffiti to learn more about the history of writing.

Alonso 1998, p. 2

Graffiti has existed at least as long as writing, although the distinctive art style we often see today is much more recent. That history is extensive, but in short the modern street art movement originated c. 1969 CE in the eastern United States. It came from urban Black American culture around the same time as hip-hop, and graffiti and hip-hop are traditionally linked. Since then, graffiti and street art have become widespread and widely appreciated by art lovers. Street artists such as Banksy are even accepted by mainstream art critics.

The earliest modern graffiti consisted of tagging, a pseudonymous signature that is usually considered vandalism. Slogans, jokes, and short poems are also common. This has the most direct connection to historical graffiti.

Graffiti serves several complex cultural purposes, primarily for marginalized groups and especially for racial and ethnic minorities. These purposes are in disregard for, or actively working against, the structures of the hegemonic class. The ongoing conflict between graffiti artists and the state that attempts to criminalize and erase graffiti is a struggle to define social reality. (Alonso 1998.) This has been referred to as a “war,” reminiscent of the War on Drugs, or the War on Terror, or the War on Poverty, and so on (Black 1997). The initial mainstream response to graffiti was predictable considering the response to hip-hop and other aspects of Black American culture. In Los Angeles, CA (and later elsewhere), graffiti was adopted by Latinx Americans, especially of the Chicano movement, and the corresponding response from white society was equally predictable.

Like jazz, hip-hop, and other Black American cultural innovations, graffiti was eventually adopted by mainstream white culture where it was commodified under capitalism. Before that, there were Black graffiti artists who successfully transitioned to mainstream art spaces, including Jean-Michel Basquiat (Gaillard 2019). However, many consider illegality an essential part of their artistic practice. The philosophy of keeping it real, which is central to hip-hop culture, entails a continual rejection of hegemony.

(See Rahn 1999)

I attack what they claim is so precious and ruin their little glass city which they (politicians) have erected somehow… We’ve proven that they can find that money to spend (cleaning graffiti); why not spend it on those who need it? At the conventions we had, we gave the money to poor people.

SEAZ, quoted in Rahn 1999

Countercultural movements have their own internal rules and power structures. Graffiti’s political functions are traditionally focused on race, ethnicity, and class. In this context, that has the effect of sidelining women, LGBTQ+ people, and people with disabilities. Most prominent graffiti writers have been cishet men, and the cishet male experience is centered. In recent decades, however, understanding of intersectionality has become more widespread, and contemporary graffiti appears to reflect this in some cases.

References

20 Similar-Looking (but different) Kanji. (2009). Nihonshock. https://nihonshock.com/2009/09/20-similar-looking-kanji/

Ali, F. (2022). Aniconism in Islam. Al-Salihat (Journal of Women, Society, and Religion) 1(2) pp. 12-27. http://al-salihat.com/index.php/Journal/article/view/12

Alonso, A. (1998). Urban Graffiti on the City Landscape. Presented at Western Geography Graduate Conference, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, February 14, 1998. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=837ef4aa68b12d2235d9721d4154830832c8b828

Black, T. (1997). The Handwriting’s on the Wall: Cities Can Win Graffiti War. American

City & County. https://www.americancityandcounty.com/1997/03/01/the-handwritings-on-the-wall-cities-can-win-the-graffiti-war/

Eubanks, C. (2016). Performing Mind, Writing Meditation: Dōgen’s Fukanzazengi as Zen Calligraphy. Ars Orientalis 46. https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.007

Furigana. (2016). Japanese with Anime. https://www.japanesewithanime.com/2016/11/furigana.html

Gaillard, H. (2019). Framing Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art from street walls to galleries and museums. In Framing Graffiti & Street Art: Proceedings of Nice Street Art Project, International Conferences, 2017 – 2018. Edwige Comoy Fusaro, Ed. pp. 59-66.

Hololive Clips and various commenters (2022). Chloe Very Excitedly Shows Her Arms But Her Handwriting Baffles Her Viewers. Clip from Chloe ch. 沙花叉クロヱ (2022): 【カメラあり】天の川流るる…星に願いを…【沙花叉クロヱ/ホロライブ】. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bXvSVDwjJw0 (©COVER)

Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/

Japanese Kanji Radicals. (2016). アーニャの日本語教室 (Anya’s Japanese class). http://japanese-language-and-culture.blogspot.com/2015/06/japanese-kanji-radicals_26.html

Kamusella, T. (2017). The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity? Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics 11(2), pp. 117–145.

Kess, J. F. (2005). On the History, Use, and Structure of Japanese Kanji. Glottometrics 10, pp 1-15.

Halpern, J. (2001). The Complexities of Japanese Homophones. The CJK Dictionary Institute, Inc. https://cjki.org/reference/japhom.htm

Mkcie B. P., S. (2019). Tri-Council declares State of Emergency for Cherokee language. Cherokee One Feather. https://theonefeather.com/

Orthodox Church in America (2001). Equals of the Apostles and Teachers of the Slavs, Cyril and Methodius. https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2001/05/11/101350-equals-of-the-apostles-and-teachers-of-the-slavs-cyril-and-metho

Paluch, A. (2016). The power of language in Jewish Kabbalah and magic: how to do (and undo) things with words. British Library. https://www.bl.uk/hebrew-manuscripts/articles/the-power-of-language-in-jewish-kabbalah

Philp, K. R. (1999). Termination revisited: American Indians on the trail to self-determination, 1933-1953.

Qian, Z. and Fang, D. (2007). Towards Chinese Calligraphy. Macalester International 18(12). http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12

Rahn, J. (1999). Painting Without Permission: An Ethnographic Study of Hip-Hop Graffiti Culture. Material History Review 4, pp. 20-38.

Smith, J. S. (1996). Japanese Writing. In The World’s Writing Systems. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, Eds. Oxford University Press. pp. 209-217.

Viejo, J. R. (2017). Faith on Parchment: Approaches to sensorial perception in two Ottonian illuminated manuscripts from St Gall. Concilium medii aevi 20, pp 129–167.

Zitkala-Ša (1921). American Indian Stories. Hayworth Publishing House. https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/zitkala-sa/stories/stories.html

平篤胤 輯考 ほか『神字日文傳 2巻附録1巻』(Shinji Nichibunden) [1],[文政2 (1819)]. 国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2562730