Let me tell you about one of my favorite things.

The pigeon and dove family, Columbidae, is a group of widespread and common birds. Members of this family were domesticated thousands of years ago and they have had symbolic importance throughout history. Many species continue to live closely with humans.

People who keep pigeons are called pigeon fanciers. As a hobby, the popularity of pigeon fancying in the United States declined in the 20th century. It has recently seen a resurgence as many people have been exploring lesser-known hobbies.

Pigeons are social, but they are territorial over their nests. They often like to nest in holes in walls and such like. A common setup for pigeon fanciers is to have an array of small boxes or compartments. These boxes, called pigeonholes, are where domestic pigeons sleep, nest, and hang out much of the time. Pigeonholes are usually large enough to accommodate two pigeons (a mating pair). Observe the following fact:

If you have more pigeons than pigeonholes, then at least one pigeonhole will have two pigeons in it.

This is called the pigeonhole principle. Pigeons are just an illustrative example. In general, if you have more items than bins to put them in, then at least one of those bins will contain more than one item. This may seem tautological, so obviously true that it’s not even worth stating. However, it is a surprisingly important idea in math.

Significance of the pigeonhole principle

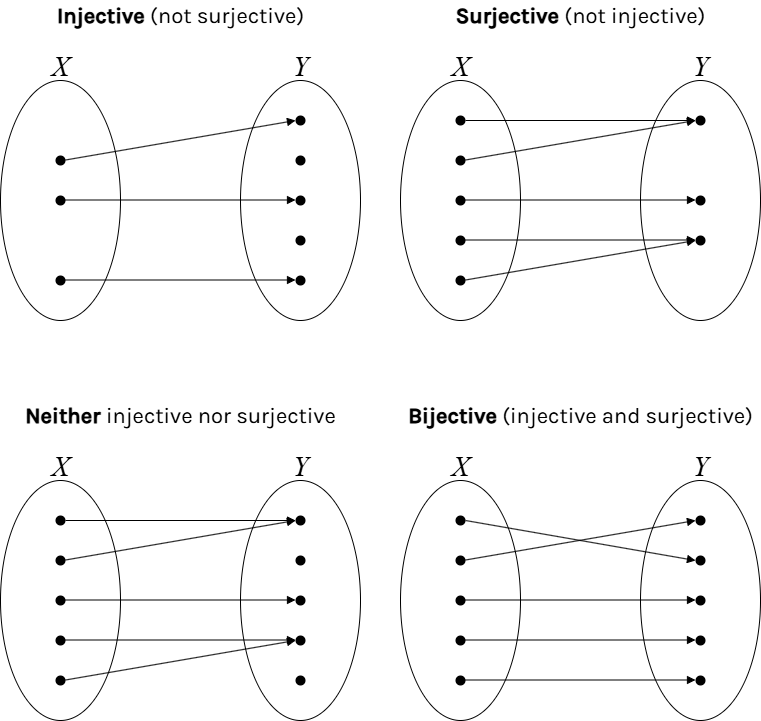

Restated mathematically, the principle says that if set X has a greater cardinality than set Y, then no injective function exists from X to Y.

Alternatively, if X has a smaller cardinality than Y, then no surjective function exists from X to Y.

A set is a collection of different things, called its elements, in no particular order. The cardinality of a set is its size, and for finite sets it is the same as the number of elements in the set.

In order to talk about injective and surjective functions, let’s consider a function F that maps X to Y. This means for each x in X, there is a y in Y such that y = F(x). In order to be a function, there must be only one y like this for each x.

However, it could be the case that multiple different elements of X get sent to the same element of Y. There could be x1 and x2 in X and y in Y such that F(x1) = y and F(x2) = y. When a function has different outputs for each input, it’s called injective or one-to-one.

Additionally, it could be the case that there exists y in Y with no corresponding x. In other words, the range of F (all possible results of applying the function to elements of X) may not be all of Y. In the case where Y is covered completely by the range, the function is called surjective or onto. (“F maps X onto Y.“)

To use the analogy, injectivity is the state of affairs where each pigeonhole has at most one pigeon in it. Surjectivity is where each pigeonhole is filled with at least one pigeon.

When a function is both injective and surjective, we call it bijective and it means there’s a one-to-one correspondence between the two sets. This can only happen when the sets have the same cardinality. A bijection would be each pigeonhole having exactly one pigeon in it.

| Injective | Pigeonholes contain at most one pigeon each |

| Surjective | Pigeonholes contain at least one pigeon each |

| Bijective | Pigeonholes contain exactly one pigeon each |

So what the pigeonhole principle is saying is that we can deduce whether or not an injective function exists if we know about the sets’ cardinalities. If X has a greater cardinality than Y (more elements), then it’s impossible to have an injective function from X to Y. One of the pigeonholes has two pigeons in it.

The principle is useful because it conceptualizes and sums up the relationship between injectivity, surjectivity, and cardinality.

| For F: X → Y | Injective function exists | Surjective function exists | Bijective function exists |

| If |X| > |Y| | No | Yes | No |

| If |X| < |Y| | Yes | No | No |

| If |X| = |Y| | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The pigeonhole principle is a genuinely useful inference tool. Let’s take a look at how math actually uses it.

The principle in action

Solutions below.

Example problem. You are grabbing socks from your sock drawer in the dark. Assuming there are several pairs of white socks and several pairs of black socks and you can’t tell the difference, how many socks would you need to take to guarantee you have a matching pair?

By the pigeonhole principle, the answer is 3. Here the pigeons are the socks you take and the pigeonholes are the possible colors of sock. Because you have 3 socks and only 2 colors they could be, one of the colors must apply to more than one sock. Ergo, you have a pair of matching socks.

More mathematically, the function in this problem maps each sock to its color. Since there are more socks than colors, we can infer that this function is not injective. Non-injectivity means at least two socks are mapped to the same color.

Extension: In general, how many socks are needed to ensure a matching pair from n different colors?

Problem 1. Prove that at least two humans with hair have exactly the same number of hairs.

Problem 2. You are grabbing gloves from a box containing 5 identical pairs of gloves. Assume that it’s dark and you can’t feel the difference between left and right gloves. How many gloves would you need to take to guarantee you have a matching pair of left and right gloves?

Problem 3. Prove that if you pick any 5 whole numbers, at least two of them will have the same remainder when divided by 4.

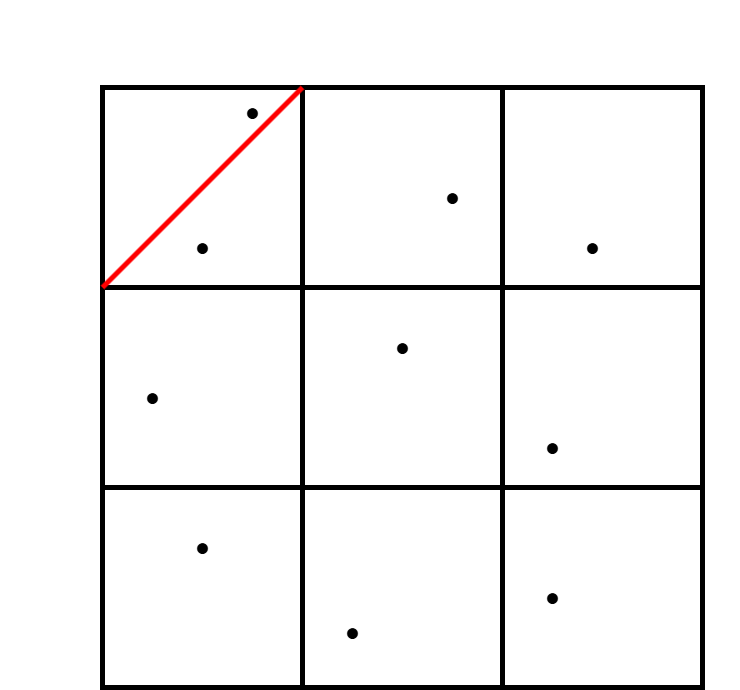

Problem 4. Suppose you place 10 points anywhere inside a 3×3 square. Prove that there must exist a pair of points within a distance of √2 of each other. (Hint: try dividing the square into pigeonholes.)

Solution to example (extension). You always need to take one more sock than the number of colors there are. Consider that if you have 17 different colors of sock and take 17 socks, it’s possible for each sock to be a different color. As soon as you take the 18th sock, it must match one of the 17 already taken, because there’s no 18th color for it to be. In general for n colors you need to take n+1 socks to guarantee a matching pair.

Solution to problem 1. The key is that there are many more humans than hairs on any single human. The maximum number of hairs on any human is also an upper bound on how many different hair counts exist. For example, if the hairiest human has 1,000,000 hairs, then there are at most 1,000,000 different possible numbers of hairs people with hair could have (1 hair, 2 hairs, …, 999,999 hairs, or 1,000,000 hairs). We use the pigeonhole principle with humans as the pigeons and hair counts as the pigeonholes.

Mathematically, the function maps each person to the number of hairs they have. Since there are fewer possible numbers of hairs than there are people to have that many hairs, the function cannot be injective. At least one hair count will apply to more than one person, thus two people have the same number of hairs.

Solution to problem 2. You would need to take 6 gloves. You have to take one more than the number of left (or right) gloves in order to guarantee that you have at least one pair of both left and right.

Note that this is similar to the sock situation, so a common mistake is thinking you need only 3 gloves, since it only took 3 socks. However, with 5 left gloves and 5 right, it is possible to grab all 3 left or all 3 right. The difference is looking for two different items instead of two of the same item. To get a pair of identical gloves (two left or two right), you would only need to take 3.

Solution to problem 3. When a whole number is divided by 4, there are only four possible remainders: 0, 1, 2, and 3. If the number is a multiple of 4, then the remainder is 0. We can be 1 away from a multiple of 4, or 2 away, or 3, but 4 steps away from a multiple of 4 is another multiple of 4. Thus, given 5 whole numbers, at least two of them must have the same remainder when divided by 4.

| … | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | … |

| … | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | … |

Bottom: Remainders after division by 4.

Solution to problem 4. Divide the square into 9 smaller 1×1 squares. By the pigeonhole principle, 10 points in 9 squares means a square must contain two or more points. The greatest distance inside a square is its diagonal, which by the Pythagorean theorem is √2 in this case. Any two points inside a small square can be no further apart than that, and there are in fact two points inside one of the small squares, so there must be a pair of points within √2 of each other.

Photo by Shankar S. (CC-BY).

The math figures in this post were made by me and are public domain (CC0).