Is a spider a bug? Is a tarantula a spider? Is a whale a fish?

All of these could reasonably be answered either “yes” or “no” depending on how these categories are understood. Is there a correct way to categorize living things?

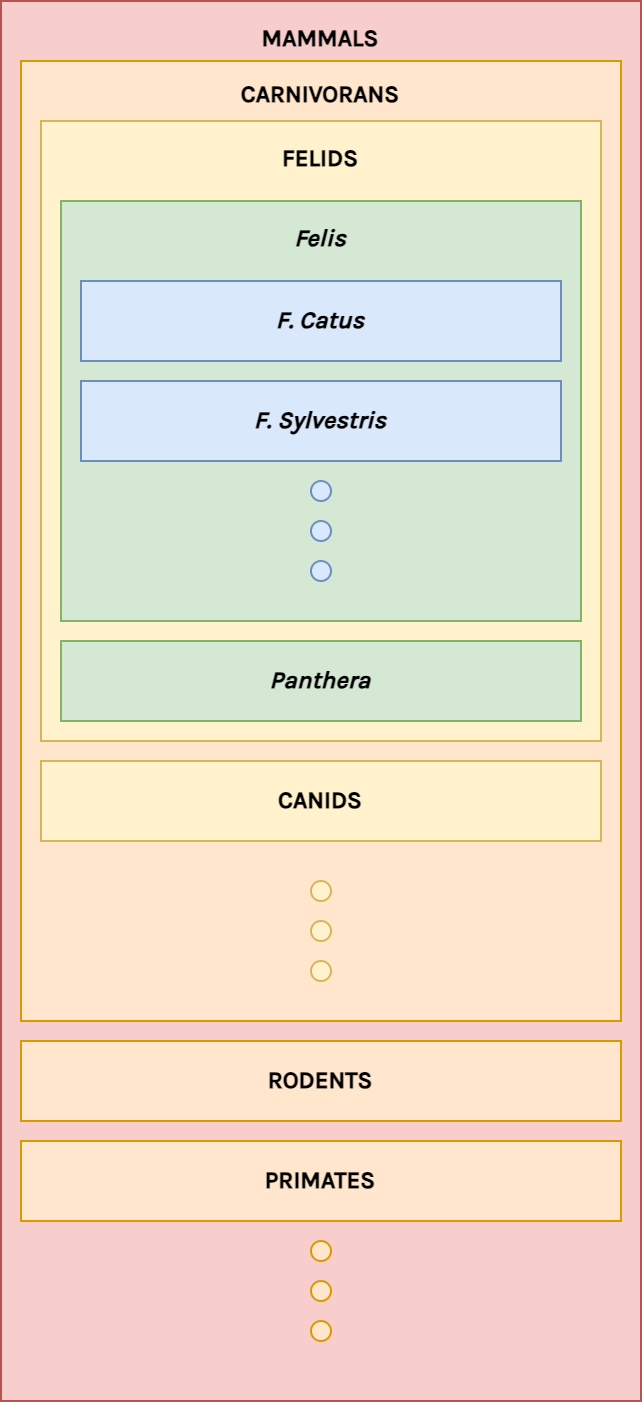

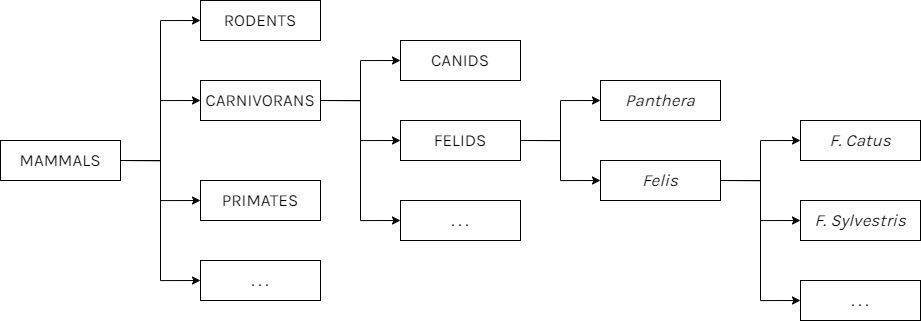

The taxonomic hierarchy

Why categorize at all?

Humans, or our ancestors, identified similarities and differences among organisms long ago. Our natural way of thinking about the world is to put things into categories, and historically we have created categories based on features that are useful or salient to us.

For example, we say there are “edible” plants and mushrooms and “poisonous” plants and mushrooms. In reality, the dose makes the poison. Every chemical is poisonous in large enough quantities and safe in small enough quantities. Some plants and mushrooms contain only a very tiny amount of a highly toxic substance, such that they are edible in small quantities. However, this nuance isn’t really useful or salient when foraging. In such circumstances, one is trying to decide whether to gather the thing or not; it’s a simple binary choice. What’s needed therefore is criteria that distinguish something that should be gathered from something that should not be gathered, which is what “edible” and “poisonous” do for us. Of course, the definitions of these categories is subject to change based on availability and need for foraged food. People who are starving will eat things that are mildly poisonous to them, and likewise people with abundant food will avoid eating anything that is suspicious or unpleasant tasting at all.

Development

In the Book of Genesis, we can see that the ancient Hebrews recognized the broad categories of land animals, aquatic animals, and flying animals. Additionally, the story of Adam naming all the animals indicates a recognition of more specific animal types (named groups of animals). How specifically people named animals at that time, I don’t know. There is also a strong separation between plants and animals, but a general recognition of both being living things.

While this is one example, it’s easy to see how humans in all places would naturally develop basic categories like this (with varying definitions for those categories). It seems similar to how children initially learn about types of living things and the basic categories they form through observation and informal discussion. In fact, it’s not too far removed from how most adults operate.

Today we talk about species. Most people have learned about species at some point. It’s a normal part of many people’s lexicon and it’s used plenty in news and media. Many people have to deal with the concept of species directly at some point in their lives, whether related to gardening, pest control, agriculture, pets, infectious diseases, etc. However, most people don’t know much more than that about taxonomy. It’s simply not applicable to their lives. Instead, humans still generally deal with categories of organisms in a highly vague or ad-hoc, but practical, way.

Systematization

Aristotle is sometimes considered the grandfather of Western taxonomy, creating the first attempt at a comprehensive categorization. The modern taxonomic system and nomenclature was created by Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century, drawing partly from Aristotle’s work. Common descent was unknown at the time, so it is only in retrospect that Linnaeus’ system reflects evolutionary relationships. His taxonomy groups organisms by shared physical features (morphology).

The taxonomy has been gradually improved over time as more species are described and as known species are better understood, but the theory of evolution was a game changer. It took time to fully grasp the implications of this. Initially, it was thought that animals with more similar morphology must be more closely related, and at the time that was the best criteria we had. As a result, the hierarchical taxonomy was just copied wholesale onto the tree of life.

This mostly worked out. Where to Linnaeus mammals were a group of animals that are similar for unknown reasons (“God just made them that way”), now mammals are considered an evolutionary clade, in other words all the descendants of a specific common ancestor. Where “mammal” used to be a mere generalization of shared traits, it’s now understood as pointing to a common ancestor having those traits.

In other words, Linnaeus would have considered it impossible for there to be an organism that is just a mammal and not a carnivoran or a rodent or any other more specific type, but for evolution the ancestor of all mammals was “just a mammal”. This would be what’s called a basal mammal, whose descendants diversified into all the mammal species we have today.

The depth of the taxonomic hierarchy is an artifact of the amount of time evolution has been occurring. A group that would have been regarded as a species at one time would be regarded as a class (for example) later on after a great deal of diversification. The system of “kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species” really only works as a snapshot, and not over time.

The problem with ancestors

Since the discovery of DNA and more specifically the development of genetic sequencing, we have discovered that evolutionary relationships are more complicated than we had thought from looking at morphology alone. Many animals that look similar are only distantly related, and other animals look dissimilar despite being closely related. This is what I might call “the fish problem” in taxonomy, since fish are a notable example and also the first example of this that I learned about.

The problem is that “fish” as we normally understand them is not a clade. Instead, it is a paraphyletic group, meaning it contains multiple related lineages while excluding more closely related species. This is because tetrapods (four-limbed animals like mammals and reptiles) evolved from fish, and you can’t evolve out of your clade.

Evolution can only create more specific subgroups. If we were to say that “fish” is a clade that includes all animals we would normally call fish, then that clade would also have to include you and me. Remember that evolution doesn’t happen by one species transforming into another, but rather a single species diversifying into multiple species.

The confusion comes in when one of those species goes on to progenerate highly morphologically derived species (i.e., they don’t resemble the ancestor species) while another progenerates morphologically basal species. Note that derived and basal here don’t mean “more evolved” or “less evolved”, they refer to different ways evolution can work in different situations.

For morphologically derived species, the environmental pressure to change is obvious, but it may be less obvious that morphologically basal species have been under environmental pressure to stay the same. Organisms don’t naturally stay the same over generations, it requires natural selection for them to do so. Often (as with fish) this situation arises from a descendant group moving into a new niche or ecosystem (in this case shallow water and eventually land) while a sister group remains in the ancestral ecosystem (the ocean).

It’s important that humans initially categorize things by features that are salient to humans. With something like body plan it is very easy for humans to see when organisms are more similar or less so. It’s easy to see, for example, that insects and arachnids are two different but related groups by counting their legs. It has only been more recently that we have been able to compare things like metabolic pathways, specific proteins, and so on.

So while gobies and lungfish appear to be related, lungfish are more closely related to humans than they are to gobies. We have three basic options when dealing with the fish problem.

- We can use “fish” to refer to the clade, making all land vertebrates fish. Confusingly this means that whales, birds, and humans are all fish.

- We can eliminate the concept “fish” from discourse since the concept is unscientific. We would characterize this as a discovery that fish, as a group, don’t exist.

- We can continue to use “fish” to refer to a paraphyletic group.

Since it seems strange to say either that I am a fish or that fish don’t exist, option 3 may appear to be the obvious choice.

Is the taxonomy the only way?

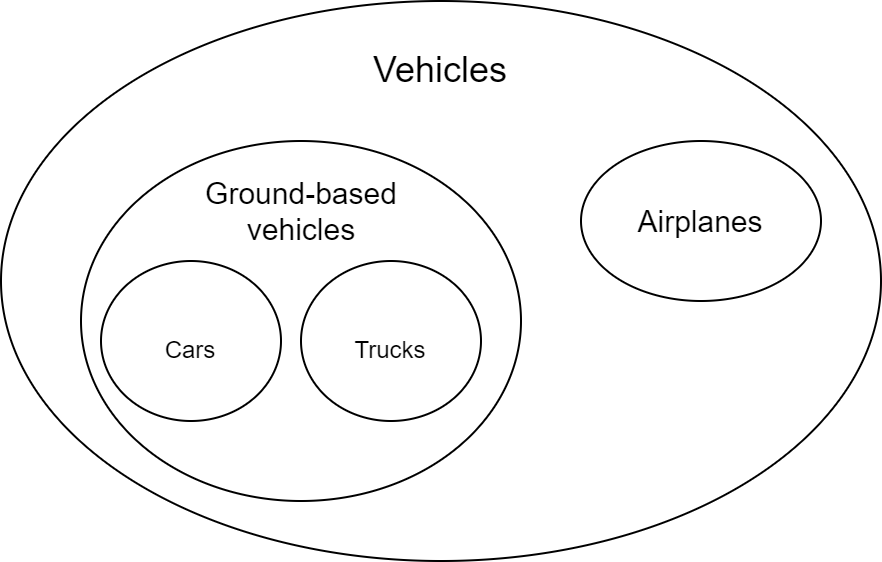

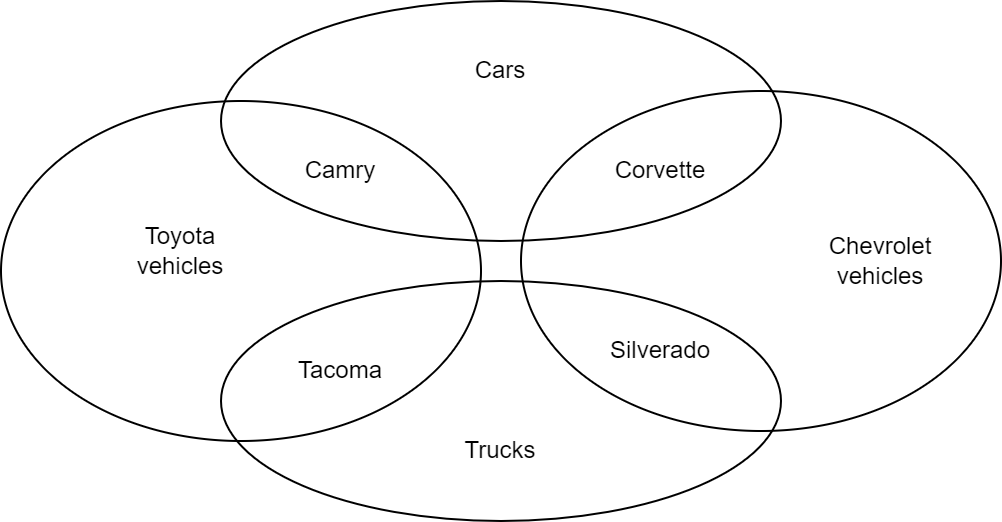

I want to digress for a moment and talk about a creationist argument against evolution. This argument is really a creationist response to the claim that the nested hierarchy structure of our taxonomy indicates common descent. According to creationists, the taxonomic system is just a way of categorizing things by similarity, like humans tend to do.

So an argument they sometimes give is what I’m calling the “descent of cars”. The purpose of this argument is to show that the taxonomy of life is not necessarily reflective of deeper relationships, and could be completely human-made, by providing an example of a similarly structured hierarchy that is clearly human-made.

The standard response to this I often hear is that the comparison isn’t valid because vehicles don’t reproduce. However, I think there is a much more devastating flaw, which is that there is no reason to prefer a hierarchical categorization over a non-hierarchical one.

This feature isn’t limited to the example of vehicles, but rather applies to many things we categorize. However, this may not be the problem for the creationist that it appears to be. After all, what does option 3 above do to resolve the fish problem but establish that there are also non-hierarchical ways of grouping living things?

Categories

Let’s consider different ways living things can be grouped. For one, organisms can be grouped by numerous basic properties like size, color, body plan symmetry, and so on. These categories are usually regarded as very informal. Of more practical importance are legal definitions: things like “invasive species”, “endangered species”, “noxious weed”, etc. are defined through statute and regulation and are subject to change depending on circumstances. These usually have less to do with the organisms themselves and more to do with how humans relate to them.

Humans’ relationship with many organisms is one of predation. Being highly generalist omnivores, there are relatively few species we are truly unable to eat, mostly only those that are extremely poisonous (and sometimes even then). As a result, we have a lot of culinary classifications and this also informs legal definitions for purposes of taxing and regulating food. Famously, tomatoes are legally vegetables and not fruit. Other culinary categories include white meat and red meat.

Then there are vague cultural or thematic groupings, like “spooky” animals (spiders, bats, ravens, etc.) or “gross” animals (frogs, worms, cockroaches, etc.). Of course, these categories are highly flexible. One cultural phenomenon is what I might call species typecasting, which primarily applies to animals. In media, especially children’s media, certain animals are typically characterized in specific ways. For example, sharks are often portrayed as villainous, owls are wise, and so on.

One important limitation of most of these categorizations is that they don’t partition the whole of the biosphere in a meaningful way. They lump the vast majority of organisms together under a “not applicable” label. For example, dividing organisms by body plan lumps all single-celled organisms together, and these are more diverse than all multicellular organisms.

The reason, of course, is that these categories have focused purposes. Culinary categories ignore all organisms humans don’t eat for obvious reasons. Stated differently, this is because the categories are human-made. They reflect human interests.

The taxonomic system, on the other hand, gives no preference or focus to any organism except to the extent that we know different amounts of information about different organisms. It is unique among ways of categorizing.

Limitations of the system

Lest we think taxonomy is a perfect reflection of reality, let’s consider what it’s really saying. First, none of the traditional hierarchical groups (kingdom, phylum, class, order, genus, species) really exist as discrete levels the way we ordinarily think of them. Cladistics do a better job, but even then there is no reason to prefer one clade over another.

So while the hierarchical structure is reflective of nature, the branching points we choose to focus on are based on what we care about and what we can find evidence for.

It’s not a flaw. In order to make sense of the world, it is necessary for humans to focus on meaningful, salient qualities. We reduce the true nuance of reality into units we can process and understand. Some estimates suggest there may have been over 1040 individual organisms in earth’s history. Any grouping of them whatsoever is inevitably human.

Even the species concept, a cornerstone of biology, can’t be defined unambiguously. Many people are familiar with the biological species concept, which says two organisms are the same species if they can produce fertile offspring. For one thing, this obviously can’t be applied to asexually-reproducing organisms. Even when applied to sexually-reproducing organisms, however, it doesn’t always work neatly. One counterexample is ring species.

Ring species are populations that are related in a specific way. For populations A, B, C, and D, if A can produce fertile offspring with B and D but not C, B can produce fertile offspring with A and C but not D, and C can produce fertile offspring with B and D but not A, are these populations members of the same species? If not, where can species lines be drawn?

According to the biological species concept, A and C are different species, but A and B are the same species and A and C are the same species. In short, being the same species is not transitive. There are many other species concepts that are more applicable in certain contexts.

Species loosely means a particular kind of organism, but it’s not the most specific we can get. Within some species there are subspecies, groups that could almost be considered different kinds of organisms. Species is more of a vibe than a natural grouping.

The right way to categorize

Something that I think gets lost in discussions of correctness is the fundamental purpose of language, which is to communicate an idea. If the speaker and the listener both understand what the speaker is saying in the same way, then it doesn’t really matter how it’s being expressed.

The reason why “whales are fish” seems wrong is because it’s misleading based on the mainstream understanding of the word “fish”. If fish are animals that live in the water and swim using fins, then whales are fish. This is the most naïve view, maybe held in ancient times. If fish are non-mammalian aquatic animals with skeletons, then whales aren’t fish. This is the mainstream view. If fish are all the animals descended from the common ancestor of all fish, then whales are fish. This is the hypercorrect scientific view.

When people disagree about this, the cause is different definitions of fish, but it’s not just a semantic argument. I think it’s a question of if and when vague, informal definitions are appropriate. At the furthest extremes are people who deny science completely, and on the opposite end people who think absolutely everything should be scientific. The extremes are clearly irrational, but there’s no clear answer as to where in between them reasonableness lies.

Some people, like me, enjoy having structures, rules, and precise definitions. I’m a math guy and neurodivergent, after all. I understand full well the desire to “ackshyually” people when their language is imprecise or unscientific. The world makes more sense with that structure and those rules, and it’s an ego boost to know something most people don’t. In general, I don’t think this behavior is productive.

Instead of pointing out what words “actually” mean, we should try to understand what the speaker means. If we are aware that something we’re saying isn’t likely to be understood in the same way by the listener, we should provide clarification. Meaning is something that constantly has to be negotiated between interlocutors.

The right way to categorize living things is with flexibility. The right category definition is whatever is most useful for the current goal. We shouldn’t cling to one definition of “fish”, we should be pluralistic. It’s not as fun as saying whales are fish, though.

Conclusions

There are lots of ways to categorize life, and these categorizations are useful in different situations. The hierarchical taxonomy is unique in categorizing every living thing (and everything that has ever lived) in the same way. The fact that it reflects the evolutionary tree of life is something special. However, it too was made by humans for humans. It’s not ideal in every circumstance.

Imprecise language can cause miscommunication and misconception, but language doesn’t need to be maximally precise all the time. In fact, vagueness is a feature of language, not a bug. It’s not worth arguing over what the correct definition of a word is; rather, we should strive to be clear about what the concepts under discussion are.

There are many misconceptions about how evolution works, how organisms are related, and so on. Some of these may be exacerbated by unscientific or folk-scientific conceptions of what certain categories include. However, I’m not a linguistic determinist, and I don’t think people are doomed to be stuck in their thinking. For some people, it genuinely doesn’t matter in their lives. In my opinion they would still gain something from learning about evolution, but there’s no reason they need to. Unfortunately, people who don’t understand how evolution works are currently occupying many of the highest seats in the US government. They do need to learn it, because their misunderstanding is actively causing harm.

Photo by Lisa from Pexels