This is a well known optical illusion in which rotation appears to be vertical motion. There are several aspects of the barber pole design which make the illusion more effective, including having multiple stripes, making the stripes different colors, and using rotation. We will strip these things away in order to see what is happening more clearly.

First of all, the motion does not need to be rotation. We could roll the cylinder out flat and think of the motion as sliding horizontally (called translation).

If we cover up all but a narrow section as the diagonal lines are translated, the illusion effect is preserved:

Additionally, we only need one line to achieve the illusion. It also doesn’t matter how thick that line is or anything like that, it just needs to be diagonal (not horizontal or vertical).

The math

So, what we have is the fact that horizontal translation of a diagonal line looks identical to vertical translation of the same. Let’s start by talking about lines and linear equations. First, we have:

Point-slope form of a line

y – y1 = m(x – x1)

This is the equation for a line with a slope of m and having a point on it with coordinates (x1, y1). Note that this can be any point on the line. If the line passes through the origin (0, 0), then we get:

Direct variation

y = mx

This is often written as y = kx where k is called the constant of proportionality, but we’re about to use k to mean something different. We can think of any line as a translation of a direct variation equation. In other words, we start with a line (with the appropriate slope) passing through the origin, then we move the line horizontally and/or vertically into the correct position.

On this basis, and along the same lines as the vertex form of a quadratic, we can write any linear equation in terms of the horizontal displacement h and the vertical displacement k (along with the slope m).

Translation of the direct variation equation

y = m(x – h) + k

Note that in other contexts, we would use a instead of m, where a represents a more general notion of “steepness factor”. In this case we will continue using m for slope.

If we simplify, we get y = mx – mh + k. Compare:

Slope-intercept form of a line

y = mx + b

Where b is the y-intercept (the y-value where the line crosses the y-axis). In other words, slope-intercept form indicates the line passes through a point (0, b). Looking at the two equations, we get:

b = –mh + k

Solving this equation for h and k respectively produces the following.

h = (k – b)/m

k = mh + b

Recall that, by slope-intercept form, a line is completely determined by m and b. This means that if we hold m and b constant, we fix the line we’re talking about to be one specific line. To make it easier, let’s say we have m = 2/3 and b = 4. So we’re talking about the line

y = 2/3 x + 4

Now, let’s inspect what the equation for k would look like:

k = 2/3 h + 4

This gives k in terms of h. Observe that this is the same equation but with h and k in place of x and y. This means that h and k can have many possible values, but they must stand in relation to each other as x and y. In particular, if h is 0, then k is equal to 4 (or b, in general).

Similarly, the equation for h would be:

h = (k – 4)/(2/3) = 3/2 k – 6

This is similar to if we solved our original point-slope equation for x (we would get x = 3/2 y – 6). While it describes the same relationship, this equation gives us h in terms of k. If k is 0, then h is -6 (or –b/m, in general). Using our two pairs of h, k values, we arrive at the equivalent equations:

y = 2/3 (x – 0) + 4

y = 2/3 (x + 6) + 0

Or, for the general form in terms of m and b:

y = m(x – 0) + b

y = m(x + b/m) + 0

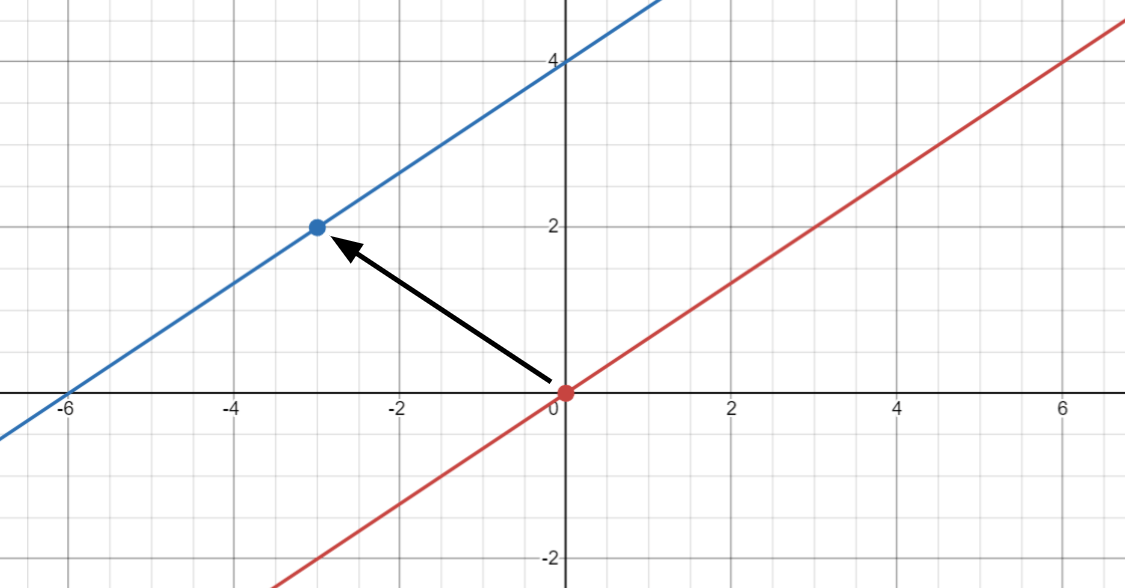

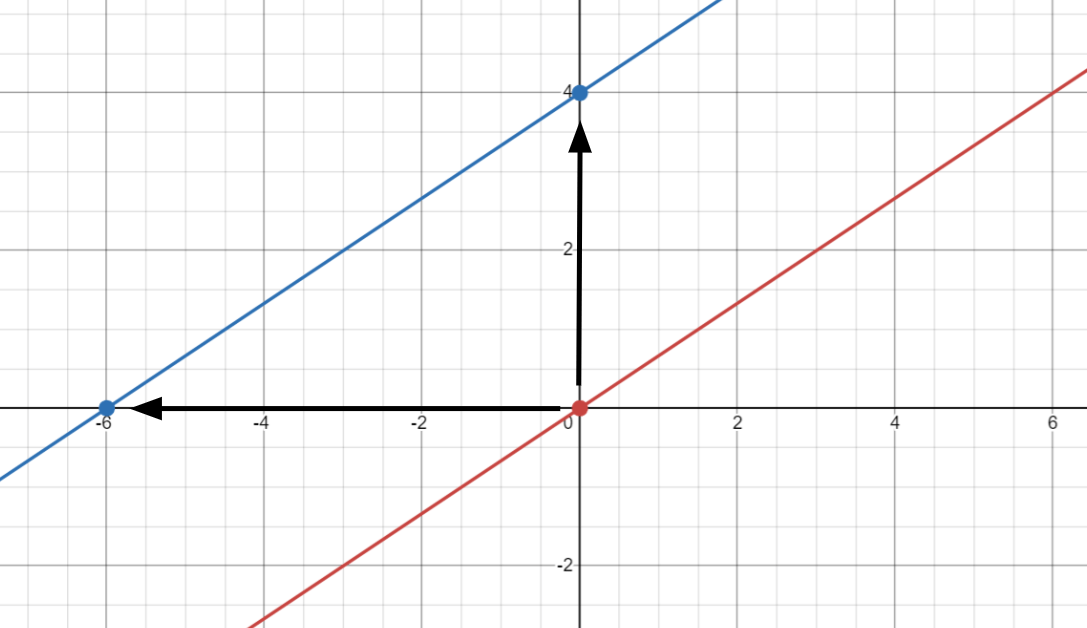

Now we arrive at the key idea. For the line y = 2/3 x + 4, we can think of it as either a horizontal translation of y = 2/3 x by 6 units to the left or a vertical translation of y = 2/3 x by 4 units upward. For any linear equation, we can think of it as a horizontal translation of the direct variation equation by –b/m units or as a vertical translation of the direct variation equation by b units.

Starting from the line y = 2/3 x, moving left 6 or up 4 gives us y = 2/3 x + 4

While we’ve been talking about translating the direct variation y = mx, this same principle applies to translating any line.

For any horizontal translation of a line, there is an equivalent vertical translation.

In particular, for a line with positive slope, moving to the left is the same as moving upward, and for a line with negative slope, moving to the left is the same as moving downward.

So in effect, the barber shop pole illusion is at its core not illusory. The rotation doesn’t just look like it’s moving upward, it’s mathematically equivalent to moving upward. In other words, for an “ideal” barber pole, there is actually no way to distinguish vertical motion from horizontal rotation. Of course, in reality, there are certain clues as to what’s going on. For example, any smudge or imperfection on the painted lines will visually indicate that there is no vertical movement, and so on. There is no way to create a mathematically perfect barber pole in real life, which is why it’s an illusion.

Featured image by Lukas Kosc.