The “traditional” methods for multiplying or dividing numbers have generally been taught by rote memorization or with minimal explanation. By reframing these processes, I hope to make it more clear what is happening.

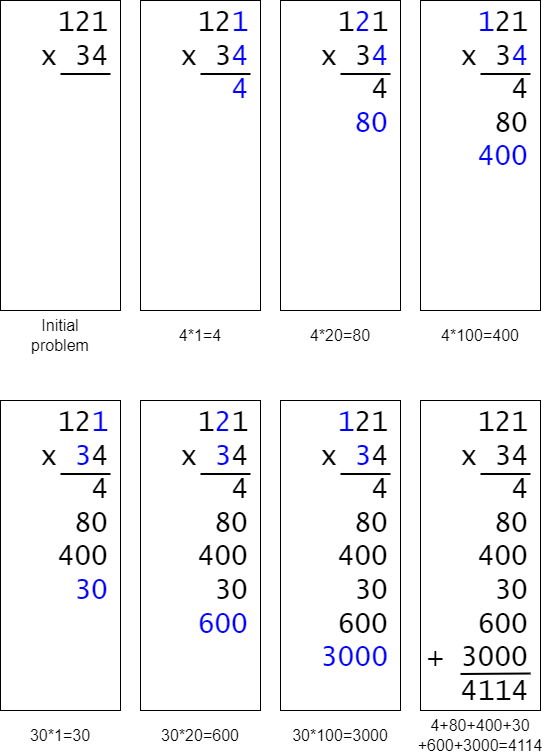

Column method of multiplication

This is similar to the column methods of addition and subtraction, although multiplication is slightly more complicated. Here’s a brief overview of the algorithm used.

First, write the two numbers to be multiplied one on top of the other, aligned by place value. It is usually easiest to place the number with more digits on top. Next, multiply columns from right to left in the following way: starting with the rightmost digit of the bottom number, multiply it by each digit of the top number from right to left, writing each result below being careful to align each product with the correct place value. Continue this process for each digit of the bottom number. Finally, add up all the products to get the final answer.

We can look at this same algorithm a different way using the “box method” (often used for multiplying polynomials and factoring). The first step is to write each number to be multiplied as a sum of its digits (preserving place value). For example, the number 35,692 would be written as 30,000 + 5,000 + 600 + 90 + 2. Next draw a rectangular box and arrange these numbers along the top. Then, draw lines through the box where the + signs would be to divide it into several smaller boxes. Do the same for the other multiplicand, placing the numbers on the left side. Now, treat what you have created as a multiplication table. Fill in each individual cell by multiplying the numbers corresponding to its row and column. Finally, add up all the numbers inside the table to get the answer.

The box method is possibly more time consuming and takes up more space, but in my opinion it makes it far easier to see what we are doing and why it works.

Long division

The long division algorithm is by far the most complicated among these “traditional” algorithms for arithmetic. The process works like this: Write the number you are dividing by (the divisor) on the left and the number you are dividing (the dividend) on the right. Draw two sides of a box around the dividend so that there is a line separating the divisor and dividend and the dividend has a line on top. Now, we can start the algorithm proper.

Determine how many times the divisor will go into the first digit of the dividend. This is the maximum number we could multiply the divisor by such that the result is less than or equal to the first digit of the dividend. Write this number below that digit, then multiply this number by the divisor to get the first digit of the quotient. Write the first digit of the quotient above the first digit of the dividend.

Next, subtract the product you calculated from the first digit of the dividend. To the right of this difference, write the second digit of the dividend. Repeat this entire process, starting from determining how many times the divisor goes into the two-digit number you just wrote (note that one or both of the digits could be zero). Keep going until you run out of digits in the dividend.

At that point, we have two options. We can continue dividing by adding a decimal point and a zero to the end of the dividend (if it doesn’t already have decimals), continuing to add zeros until the division is complete. Alternatively, the final difference we arrive at with no more digits left in the dividend to use can just be treated as a remainder. This also makes it easy to write the quotient as a mixed number.

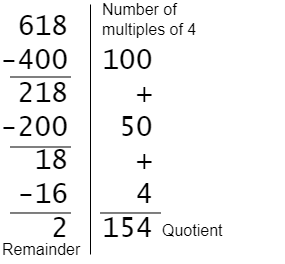

This is based on the Euclidean algorithm which just involves subtracting off multiples of 4 from 618 and keeping track of how many multiples we subtract. It does not actually matter how we do the subtraction as long as we keep track of it.

This approach can be easier because it does not strictly require coming up with the “right amount” to subtract each time. It’s possible to perform the algorithm more slowly (less efficiently), for example we could subtract 40 at a time over and over and we’d just need to do more subtractions.