Phases of matter and chemical mixtures

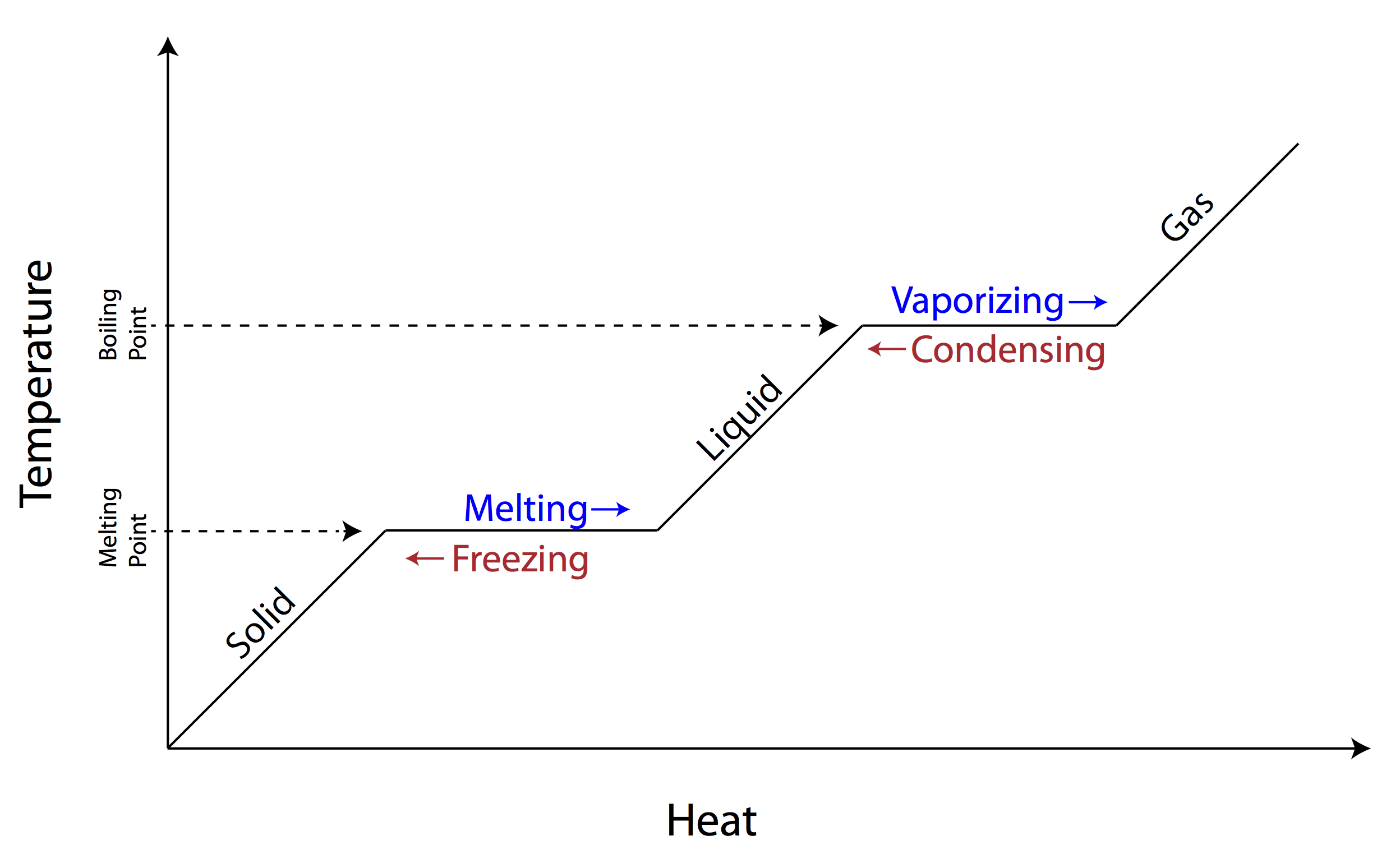

Under most normal circumstances, chemical compounds exist in one of three states or phases: solid, liquid, and gas. At normal atmospheric pressure, there is a specific temperature at which a given substance will transition from one phase to another. Many substances in the kitchen which are solid at room temperature burn before melting if exposed to oxygen in the air. In general, the range of temperatures in the kitchen is from 0° F (-18° C) in the freezer to around 500° F (260° C) at the hottest oven temperature. The flame of a gas stove can get much hotter, potentially over 3500° F (1927° C) (Gas South 2023, Wikipedia 2023).

Much of food chemistry involves heterogeneous mixtures of one or more phases, such as colloids (colloidal suspensions). These are mixtures in which one substance is finely dispersed inside another substance and include aerosols and emulsions. For example, whipped cream consists of gas bubbles dispersed in a liquid, gravy has solid particles dispersed in a liquid, mayonnaise has liquid droplets dispersed in another liquid, and gelatin consists of liquid dispersed in a solid.

Butter is a good example of the complexities of such mixtures, consisting of roughly 80% fat, 15% water, and 5% non-fat milk solids (such as whey protein, minerals, etc.). At freezing temperatures, butter is quite hard. It gets progressively softer as the temperature increases, melting at around 90° F (32° C). At 212° F (100° C), the water starts to boil off. At around 350° F (177° C), the milk solids start burning, and at around 450-500° F (232-260° C) the fat itself will burn (Beninati 2022).

Phase transition and temperature control

One of the principal problems in cooking is how to rapidly add heat to a substance without burning it. This is particularly important for foods that degrade or burn quickly at high temperature. Phase transitions end up helping us with this for the following reason: when water is at 212° F (100° C), any additional heat energy will go towards vaporizing the water. The water importantly cannot exceed this temperature as a liquid-and-steam mixture (under normal conditions). This means that anything in contact with boiling water cannot be heated higher than 212° F by the water.

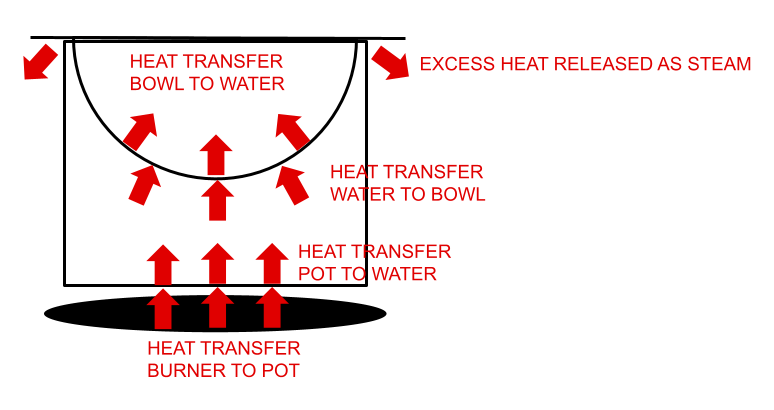

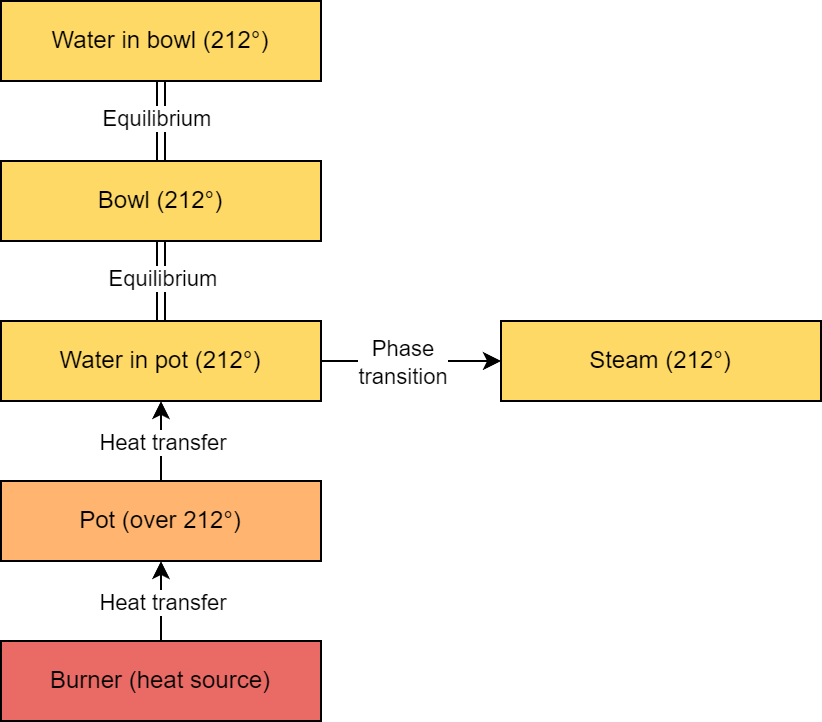

Let’s imagine we create a double boiler by placing a bowl on top of a pot of water. Heat energy from the stove burner warms the pot which in turns warms the water. The water then warms the bowl which warms the contents of the bowl. Let’s say the bowl just contains water.

As energy continues to flow into the system via the burner, the temperature of the water in the pot will not exceed 212° F. All of the excess energy goes into breaking molecular bonds in the water, turning it from liquid to gas.

Once the bowl and its contents reach boiling temperature, they are in thermal equilibrium with the boiling water in the pot, and no additional heat transfer is possible. With no excess heat being transferred to the water in the bowl after it reaches this temperature, it will not boil (though some vaporization will occur).

In reality under normal conditions, the water in the bowl will lose energy to the cooler surrounding air and to evaporation, so heat will continue to flow into the bowl of water but the temperature will not exceed boiling. Note that a double boiler only requires the water in the pot to be simmering, since boiling the water faster just creates steam faster and otherwise doesn’t affect the process.

The point is that, for example, butter in a double boiler will melt but never burn.

High altitudes

The temperature at which a phase transition occurs, like the boiling point of water, depends on pressure. Changes in air pressure from day to day due to weather and such has little effect. However, at high altitudes on the earth, air pressure is low enough that there is a noticeable difference in boiling temperature, and this has consequences for cooking.

As atmospheric pressure decreases, water boils at lower temperatures. At sea level, water boils at 212 °F. With each 500-feet increase in elevation, the boiling point of water is lowered by just under 1 °F. At 7,500 feet, for example, water boils at about 198 °F. Because water boils at a lower temperature at higher elevations, foods that are prepared by boiling or simmering will cook at a lower temperature, and it will take longer to cook.

USDA

Baking is also particularly affected. The King Arthur Baking Company, for example, lists several things that must be adjusted for baking at high altitude, including oven temperature, baking time, and liquid content.

This also means that the temperature of a double boiler depends on altitude. At higher altitudes, water boils at a lower temperature, and thus the bowl will not get as hot.

References

Beninati, D. (2022). How to Prevent Butter from Burning. Food Network. https://www.foodnetwork.com/how-to/packages/food-network-essentials/how-to-prevent-butter-from-burning

Gas South (2023). Natural Gas Stoves: Everything You Need to Know. https://www.gassouth.com/blog/natural-gas-stoves

King Arthur Baking Company. High-Altitude Baking. https://www.kingarthurbaking.com/learn/resources/high-altitude-baking

USDA. High Altitude Cooking. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/high-altitude-cooking

Wikipedia (2023). Gas burner. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gas_burner