In Part 1, we discussed the origin of play, the relationship between game mechanics and interactive narrative, and the specific examples of Tetris and Monopoly. In this post, we’ll take a look at what happens when gameplay and narrative clash, what can be done to avoid it, and how it can be used to the game designer’s advantage.

Ludonarrative dissonance, diegesis, and skeuomorphism

In some cases, a game mechanic is outright contradictory to part of the narrative. This phenomenon has been termed ludonarrative dissonance. A common example in video games is what is known as “winning the fight but losing the cutscene.” In this situation, the player character (PC) is able to defeat their opponent in gameplay, but the narrative insists on the PC losing anyway. Another example is when a game’s story characterizes the PC as a noble hero, while its gameplay allows (or even incentivizes) immoral behavior like stealing and murdering. Ludonarrative dissonance is usually regarded as a design flaw. It can break immersion and the suspension of disbelief, reducing the enjoyment of playing the game.

Visual elements of gameplay

Immersive games sometimes try to minimize non–diegetic elements. In narrative media (first in film and later in other media), the term diegetic refers to objects or phenomena that exist within the world of the narrative. This was first used to distinguish between diegetic sound (which a character might be able to hear) and non-diegetic sound (which only the audience can hear). In video games, non-diegetic elements may include background music, tooltips, health bars, objective markers, speech bubbles, and so on. In some cases, user interface (UI) elements incorporate skeuomorphism, i.e. they are made to resemble real-world objects or materials. This was perhaps most popular around the turn of the millennium and the time of transition from 2D to 3D, and went somewhat out of the mainstream with the rise of “AAA” gaming. The modern game industry is characterized by a wide-ranging plurality of design styles, including both skeuomorphic and non-skeuomorphic.

While there is some overlap, the important difference between diegesis and skeuomorphism is in whether something is being presented to the player character or to the player. In first-person perspective games, the distinction can be especially blurry.

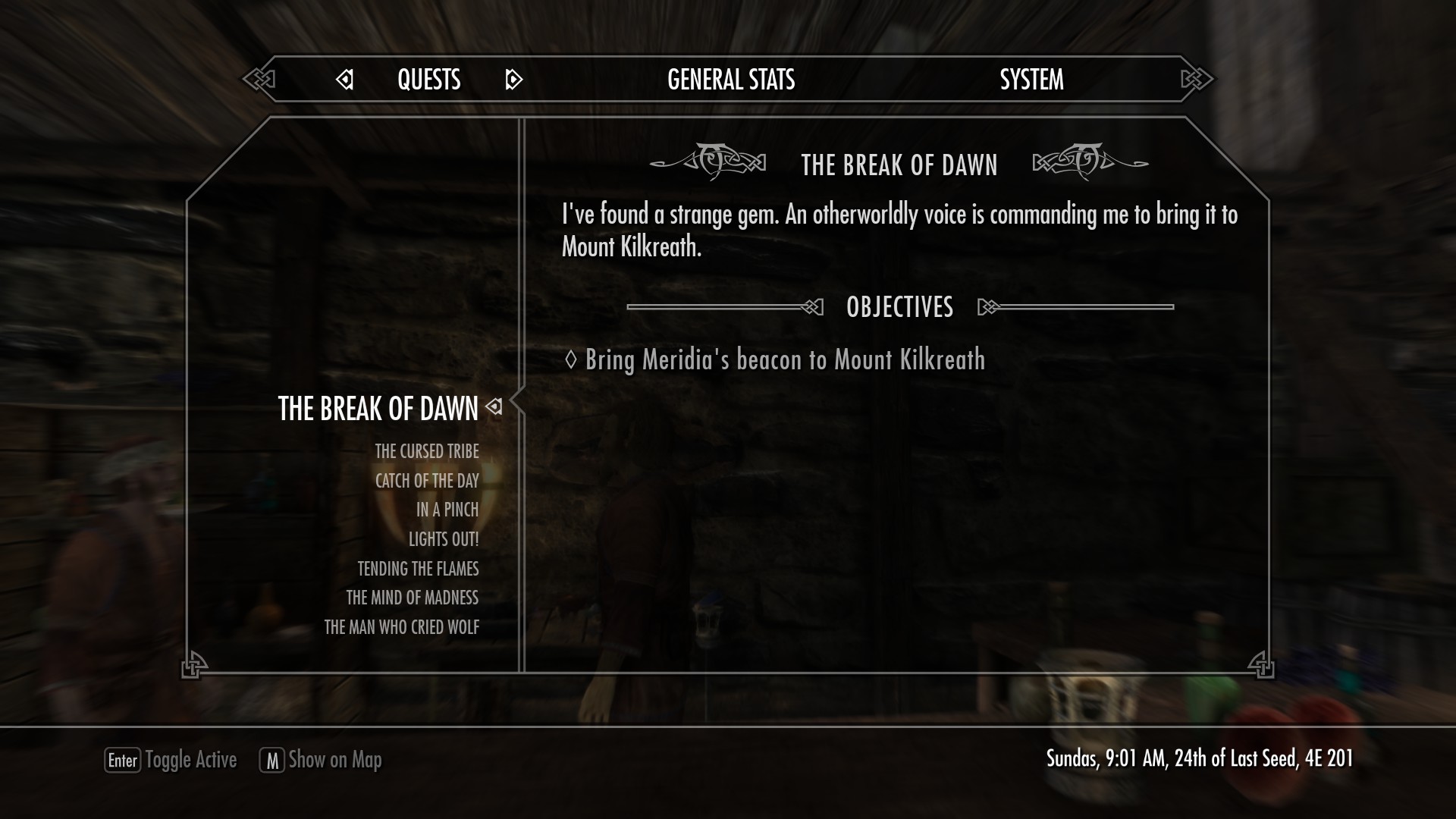

In Morrowind, a roleplaying game (RPG) that is often played in first person, the quest journal is supposedly being read by both the player and the PC when it is presented on the screen. Note that the buttons at the bottom of the journal are nondiegetic (Options, Prev, Next, Close). A later game in the same series, Skyrim, maintains diegetic journal text written in the first person by the PC. However, this text is now presented in a nondiegetic menu.

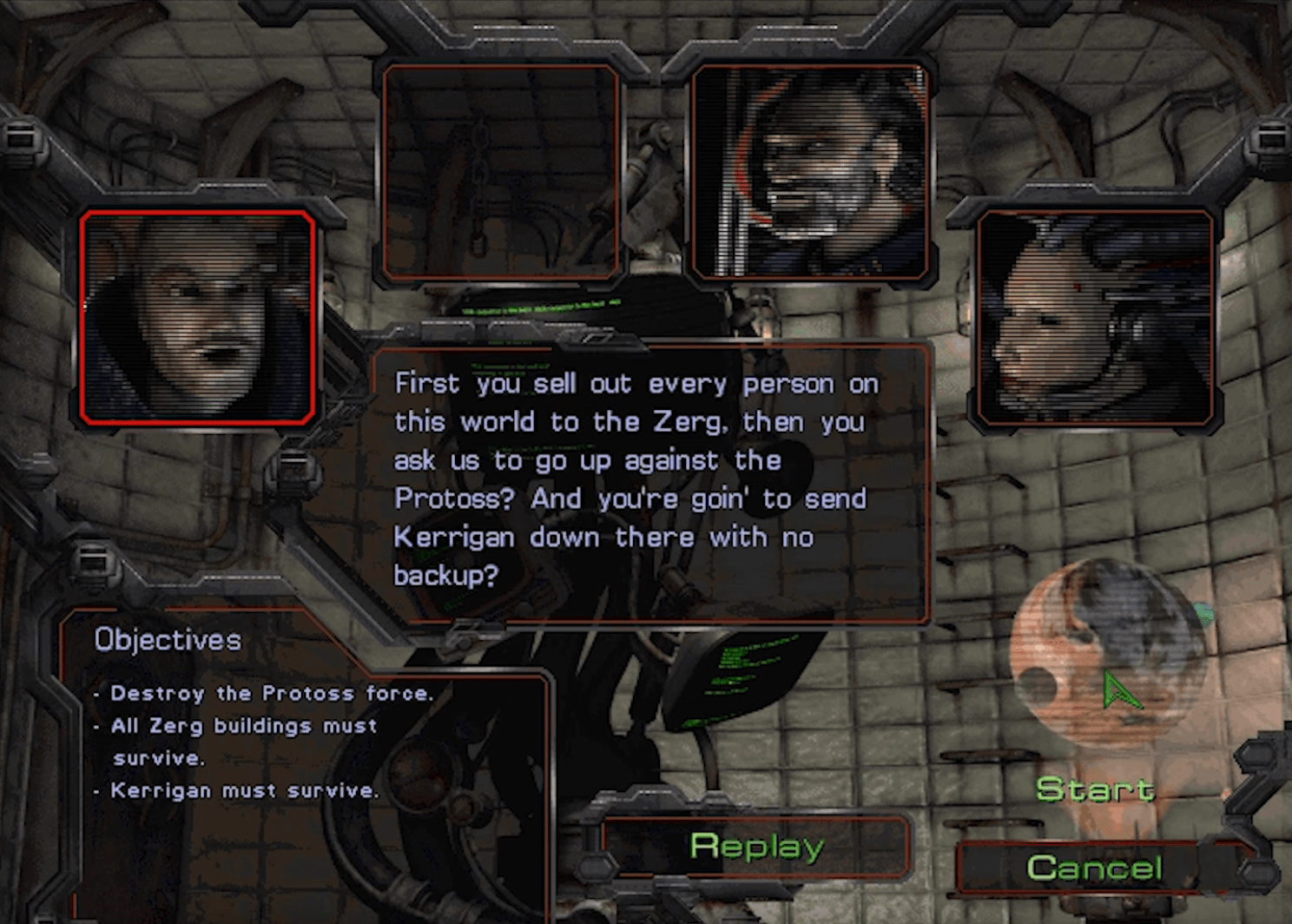

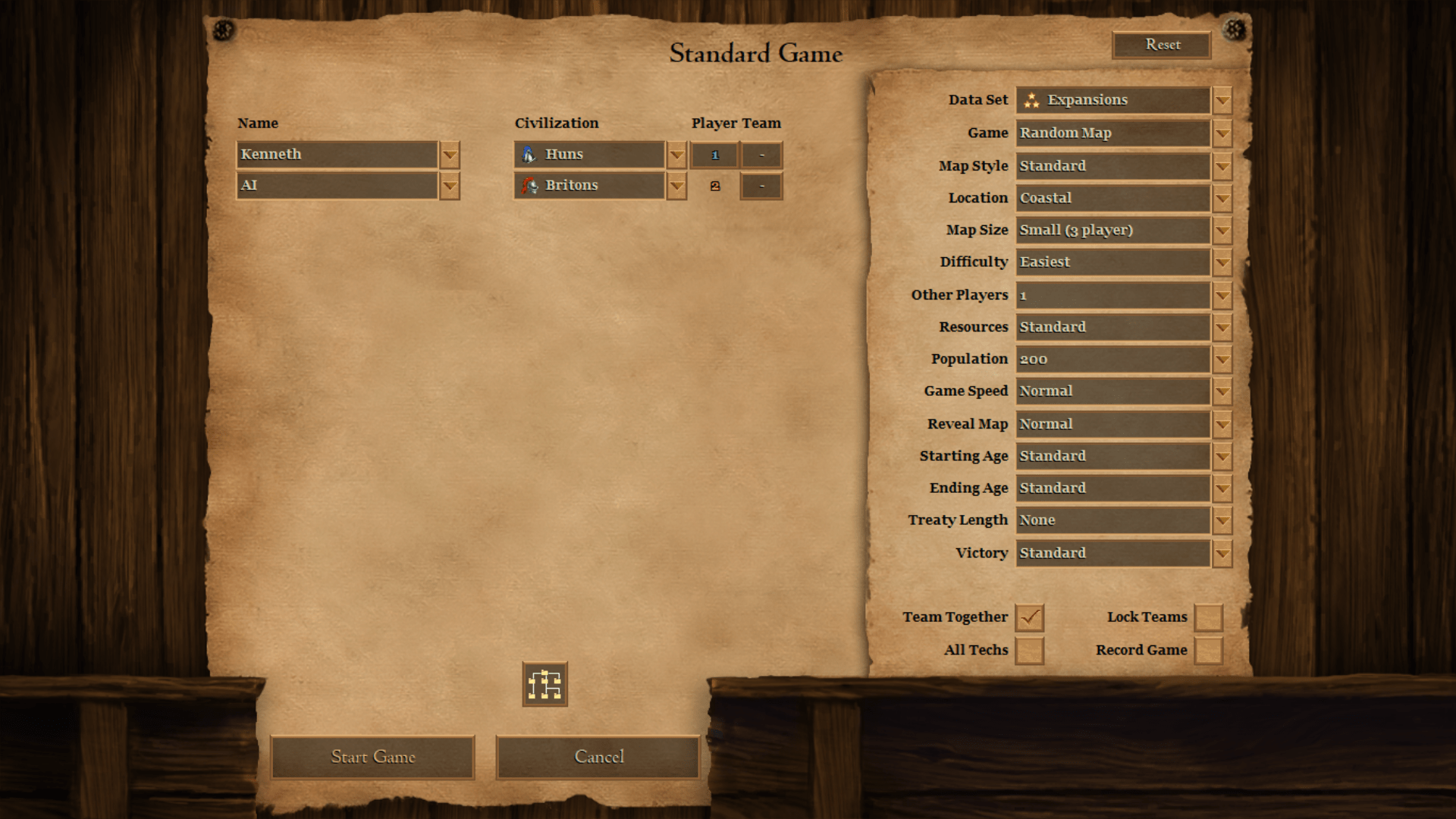

While not a first-person game, a plot concession of the strategy game Starcraft is that the player is transparently taking on the role of a commander. By transparently I mean there is no intermediate PC, unlike Morrowind and Skyrim which could be said to be “opaque.” Many real time strategy (RTS) games use a similar concession, including Age of Empires which is mentioned below. These games are typically not very immersive, given the unrealistic camera perspective and the ways in which the player controls the characters.

Another example of taking on a role opaquely is Dead Space, which uses an over-the-shoulder perspective. Many UI elements are diegetic, including the PC’s health bar (represented by the vertical lines on the PC’s back) and many menus.

A significant difference between this approach and e.g. the quest journal in Morrowind is that the player’s ability to see these elements is sort of “diegetically incidental.” The player in Dead Space doesn’t see exactly what the PC sees. From a design perspective, the purpose of making these elements diegetically visible is clearly to present them to the player, however the concession of the game world is that the player does not exist at all. In most games, if the player’s nonexistence is a concession and something needs to be presented to them, the solution is to use non-diegetic UI. Dead Space is somewhat known for this creative solution which largely eliminates the need for non-diegetic elements.

If non-diegetic UI must be used, some game designers have leaned heavily into skeuomorphism to reduce feelings of dissonance between the game and the game world. Or, to put it positively, to increase feelings of consonance between the game and the game world. This approach uses the appearance of real-world objects and textures without any world-context around them.

How game systems are presented or characterized can cause or prevent dissonance. A common system in many games is the respawn, wherein the PC is revived from death. A similar system is to send the PC back in time to a save or checkpoint upon death. These systems are usually presented as being wholly non-diegetic or not commented on at all. In some cases, there is a token diegetic explanation given.

However, some games integrate systems like this heavily into the game world as part of the game concept. In Destiny and Destiny 2 for example, the PC is a resurrected warrior that diegetically has the ability to revive from death.

Tutorials: communicating with the player

Board and card games typically include instructions that are wholly extradiegetic. While some video games have followed this approach, many (particularly modern mainstream games) incorporate a tutorial into gameplay. The degree of diegesis of a tutorial varies greatly, but they are necessarily transdiegetic; that is, they actively bridge the gap between the diegetic and the non-diegetic. It tends to be prior to (or concurrent with the development of) the suspension of disbelief.

Tutorials by their nature tend to cause ludonarrative dissonance. Many developers seek to alleviate this feeling by subverting player expectations, for example by inserting lampshading or scares. Lampshading, or putting a lampshade on something, is a form of fourth wall breaking that involves calling attention to an inconsistency, trope, or flaw. An example would be a character in a superhero movie saying, “it’s like we’re in a superhero movie!” in reaction to some unbelievable phenomenon.

By scares above, I mostly mean jump scares. Even in a horror game, a tutorial often feels like it should be free of genuine danger. This is perhaps in part because of ludonarrative dissonance distancing the player from the game world emotionally. By interrupting a tutorial, especially during a learning moment, the player can be caught off guard and extremely startled by a jump scare. It is a well known meme on the internet to send someone a video that instructs them to focus carefully on something, then jump scares them with a scary face and loud noise. Pranksters and game devs alike understand this strategy of getting the victim to focus on something before initiating the jump scare. Moreover, building moments in the tutorial where the player would expect a jump scare but don’t get one builds suspense effectively.

In both of these examples, the developer intends to dispel dissonant feelings by overriding them with other emotions (humor, fear) or otherwise distracting the player. When successful, this can lead players to feel that they were immersed right away.

Exposition and dialogue

Video games have taken a wide variety of different approaches to dialogue and exposition delivery. On one extreme, some games feature frequent cutscenes that the player is expected to sit back and watch. In many cases, these can feel detached from gameplay. Some developers implement interactivity mid-cutscene through quick time events (QTEs) and dialogue options, but these often feel token and overly “gamey.” When it comes to dialogue with the PC, there are some particular pitfalls. In an RPG, you might want to play your character in a certain way which gameplay allows, but then there might not be dialogue options that reflect your playstyle. This is especially true in fully voice acted games, since additional voice lines take space, time, and money. In my opinion, Skyrim has this problem. The PC could have a wide variety of personalities, but dialogue options tend to characterize them in a specific way.

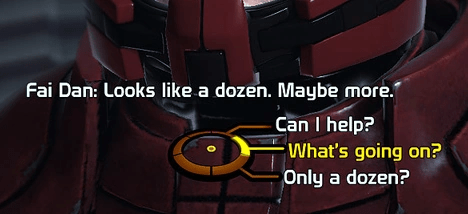

Certain games feature dialogue options that lie along a one-dimensional scale from “bad guy” to “good guy.” This was a somewhat divisive feature of the Mass Effect games.

In order to avoid these issues, many games feature a silent protagonist. The quintessential silent protagonist is Gordon Freeman from the Half-Life series.

Man of few words, aren’t you?

Alyx Vance, Half-Life 2 (Valve, originally released 2004)

In the first installment, Gordon is alone for most of the game. There are virtually no cutscenes, although there is a rather long intro segment and there are a couple of scenes in which characters talk at the player. Exposition is delivered to the player slowly over the course of the game, often not in words but in experiences. The introductory tram ride as Gordon goes into work at the Black Mesa research facility one morning provides the first views of the facility, and during the ride there is a recorded voice on the intercom reading out announcements that provide additional context. The intro quickly establishes that Black Mesa is located in the desert of New Mexico and develops a wide range of super-advanced and dangerous technology. As soon as Gordon arrives at his stop, things are already going wrong, foreshadowing the coming disaster. Gordon prepares to perform a high-stakes experiment with unknown (to the player) significance, and as soon as he does, all hell breaks loose (almost literally). For the rest of the game, Gordon is forced to traverse the facility, mostly on foot, while fighting off aliens and later soldiers. As the game progresses we get a sense of the massive scale of Black Mesa and just how many different things they were involved with.

Much has been written about Half-Life’s atmospheric storytelling. I won’t rehash it all here. What is relevant and notable is that the game has astonishingly consonant gameplay and plot. Gordon’s actions can be summed up as “the right man in the wrong place.” He is a mostly ordinary man who finds himself in extreme circumstances and he just happens to have the skills necessary to deal with it. He’s not a soldier, he’s a scientist under duress.

Many other games, especially since the success of Half-Life, have followed this model. By keeping explicit exposition and dialogue to a minimum, the game world and characters can be shown directly through gameplay, which will tend not to produce ludonarrative dissonance. Of course, this strategy does not work for all types of games.

A different solution is to put story information in notes or audio logs that the player can find as they go. In System Shock, there are virtually no living characters aside from the PC, so there is no dialogue to be had. This information is presented to the player in audio logs instead. These too have now become somewhat trite and “gamey.” Many games struggle to justify why a character is writing or recording certain information.

Notes are especially prevalent in the horror genre, since developers often want to keep the PC alone. In the satirical horror game Spooky’s Jumpscare Mansion, notes and other horror game tropes are lampshaded.

What is this?

Wow, what a mansion!

Inside another mansion.Maybe I’ve

Spooky’s Jumpscare Mansion (Lag Studios, originally released 2014) via the wiki

made it all the way to the end of

the house. Maybe this is like a

resting place or another entrance

perhaps? Whatever the case, I

think this is a good spot to rest.

In order to survive this house I need

to keep writing notes.I must do everything a central

protagonist would and hope this is

one of those stories.‘Insert Obscure horror reference that

Spooky’s Jumpscare Mansion

no one gets and misinterprets as

instructions somehow’