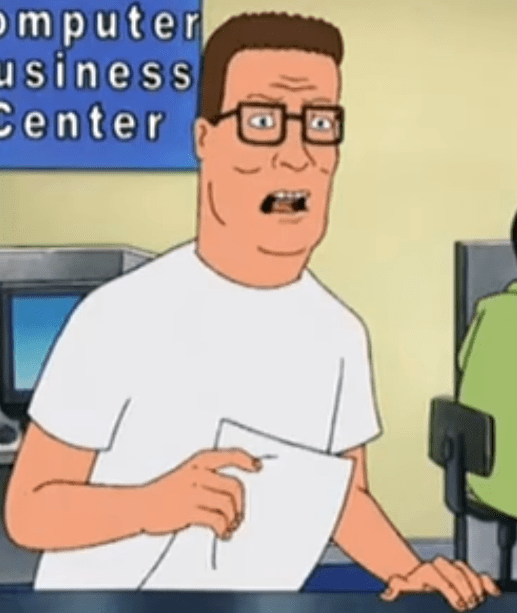

Do I look like I know what a JPEG is?

Hank Hill

In a computer, all information is represented as bits, strings of zeros and ones. However, bits can more or less be interpreted as generic numerical data written in base 2 instead of as decimals. In other words, in a computer, all information is represented as numbers. Instead of being one long number, the digits in a data file are broken into chucks such that the file is interpreted as a sequence of numbers.

In order to represent an image digitally, we need a way of encoding it as a sequence of numbers. First, we think of the image as being made up of pixels, tiny single-color squares, arranged in a rectangular array aka matrix. We need to use some numbers at the beginning of the file to provide metadata so that the image can be decoded: for example, we might specify a file name, the image dimensions and resolution, the format we’re using to encode the pixels, and so on. When we are ready to represent the pixels themselves, we just need enough data to specify a single color. There are multiple ways to represent color, for example RGB specifies a color using three numbers, each ranging from 0 to 255 (or 0 to FF in hexadecimal), representing the amount of red, green, and blue. Alternatively, HSL specifies a color using a different three numbers: hue, saturation, and luminosity.

So the actual data of an image (excluding metadata) consists of a matrix of ordered triples of numbers each ranging from 0 to 255. It takes 8 bits or one byte to represent each of these numbers in binary, so the amount of data required to represent an m by n image is:

m * n * 83

For a 300×500 image, this would be 76800000 bits or 9.6 MB (megabytes). In reality, an image of this size is typically less than 1 MB even for a lossless image format, and potentially only tens of KB (kilobytes). Clearly, something is happening to reduce the actual amount of data we need to record.

Let’s consider a binary string like 100011111111100000011111. This is 24 bits or 3 bytes. Here’s another way we can express the same string: 11.30.91.60.51 (dots are added to make it visually clearer). In this scheme, we state how many of each number in a row there are going left to right through the string. In binary this new string would be: 11.110.10011.1100.1011 which is 18 bits. The same information can be stored using few bits of data, and we didn’t lose any information by doing this. Clearly, this scheme’s effectiveness depends on the string we start with. Something like 1111111111 would be reduced by a massive amount while something like 1010101010 would actually become larger. The more redundant a string of bits is, the better this works.

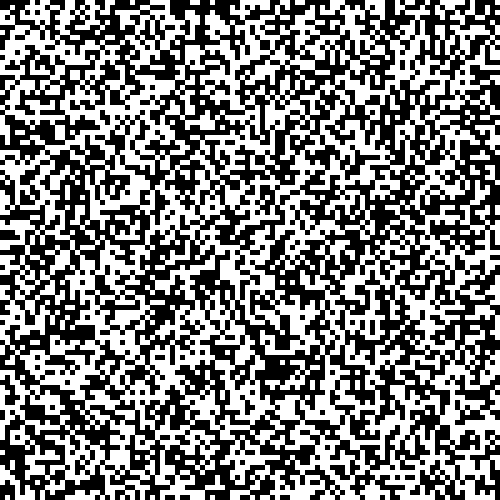

Consider if we counted two bits at a time: then 1010101010 would be 5.10 or 101.10, though 1111111111 would not get compressed as much. In fact, what is critical here is not redundancy per se, but patterns that can be described mathematically using fewer bits. Many kinds of sequences, even non-repeating ones, can be described concisely with math. Even so, the simpler the pattern, the more compressed it can be. The kind of image that takes the most data to represent, then, is an image with virtually no patterns at all, i.e. random static. Below are two images with the same dimensions and the same file format (lossless PNG), but the one on the right is over 35 times the file size of the one on the left.

It turns out to be helpful that our data is already arranged in a matrix, because this enabled us to use linear algebra techniques. For example, we can reduce matrices using sequences of elementary row or column operations (Gauss-Jordan elimination). We don’t need the data to explain what each operation is doing; it just needs to be able to reference a pre-established code indicating the operation. Reduced matrices can be less than half the amount of data of the original. For an invertible matrix, the reduced row echelon form is always the identity matrix I.

For memory efficiency and other reasons, it’s often undesirable to do math on the entirety of an image at once. Instead, many compression algorithms divide up an image into blocks or submatrices, and compress each block individually. This is the reason for the “blocky” appearance of a highly compressed JPEG.

JPEG is a lossy form of compression, meaning some data is discarded in the interest of making the file as small as possible. In general, JPEG compression is effective and unnoticeable for high resolution digital photographs, but does not work as well for pixel-sharp computer graphics. This is why photos are often JPEGs while computer graphics are often PNGs.

When considering what information to throw away, it is important to consider how human vision works. First, humans are much more sensitive to changes in brightness than to changes in hue. As a result, retaining information about brightness while discarding some of the color information (via undersampling) will not be very noticeable. Second, human vision is more sensitive to sharp outlines than tiny details. In order to account for this, the JPEG algorithm breaks the image into blocks of pixels and determines how sharp the contrast is within that block. For example, one block might contain white pixels and black pixels with very little gray, while another block may consist only of different shades of gray. The grey block can be more severely compressed without making a noticeable artifact in the image.

Note that the lossy part of the JPEG algorithm does not actually reduce the amount of data at all. What it does instead is make the image less noisy, i.e., more patterned or redundant, so that it is more compressible under a lossless compression algorithm. Lossy compression is a way of “simplifying” the image data so that it can be described more concisely with math. Comparing with our example of the binary strings above, it would be like changing:

1111100000100010

to:

1111100000000000

You can check for yourself that the scheme we initially came up with above is much more efficient in the second case. This is similar to the idea of rounding numbers.

Reference

Jennings, C. G. (2021). How JPEG works. https://cgjennings.ca/articles/jpeg-compression/