Magic words, mysticism, curses, and prayer

A long-held belief within virtually every culture across the world is that language has a special power to affect the physical, mental, or spiritual. There are some prominent examples that are worth looking at in more detail.

There are essentially two ways in which a written word can have power: by representing an utterance that has power, or by virtue of the symbols’ geometrical shapes (or both).

Invocation, the power of true names, and the Rumpelstiltskin principle

Speak of the devil, and he shall appear.

English folk saying

A very common belief, especially historically, is that proper names can represent a person’s true character, destine them to certain life outcomes, or hold power over them. In a law-of-attraction-like principle, many believe writing or uttering a thing’s name will attract its presence. This is the source of some taboos (in the sense of forbidden words) for which euphemisms were created.

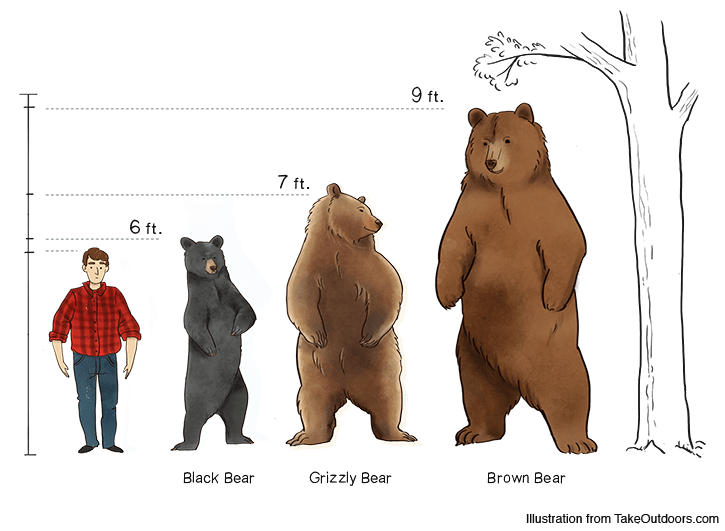

… in prehistoric and later times the great Brown Bear was the largest predator of the northern European forests and the central Asian highlands. Very likely he was the peer of the nine-foot giant Kodiak, a species that still makes awesome tracks in the narrow confines of Alaska. So great was the fear of Brown Bear and his powers that in most places he came under that taboo associated with nominal sanctity which is normally extended to such powers as are too dominant and imminent and which, for one reason or another, are deemed too supernatural to be subject to ordinary controls. The taboo is reserved for those major divinities and forces whose names one must not speak aloud lest unknown consequences result from the invoking of them. Thus, periphrastic epithets which identify but do not invoke are used instead, and sometimes these even supersede and thrust the actual name into oblivion. That this was a common practice in referring to Bear has been demonstrated by Meillet. Conversely, in Greece and Italy where Bear had limited range because the lion was dominant instead until the 8th [century BCE] in Greece at least, a taboo name for it rarely arose, so that Latin freely used the generic term ursus and Greek arktos which has the same root as the Sanskrit [rksa]. Where Bear reigned, however, among the languages of the North the Indo-European nomenclature was suspended and the beast identified periphrastically, as bruin, bear or braun, all meaning “The Brown One.” The Baltic people preferred alluding to him also as ”The Big Foot,” and, most tellingly, “The Glory of the Forest.”

Thalia Phillies Feldman 1974, pp. 4-5 (italics in the original, bolding mine.)

The word invoke derives from the Latin vocō/vocāre, meaning to use one’s voice to call by name, summon, or beckon.

Another well-known usage of this periphrasis or euphemistic naming is J.K. Rowling (the now-infamously anti-trans author) using “He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named” or “You-Know-Who” to identify the main antagonist Lord Voldemort without invoking him. Early in the Harry Potter series, it was implied that people were merely afraid of mentioning his name, however it was later established that the name had a literal curse placed upon it that made it taboo. (See also: my blog post An analysis of biological arguments against transgenderism.)

A different perspective is that using a thing’s name grants power over that thing. This is not always a mystical power. For example, in the story of Rumpelstiltskin, popularized by the Brothers Grimm, the titular character makes a deal with the protagonist, the queen, in which she will be released from her contract with him if she can guess his name within three days. She then spies on him and hears him singing to himself, thereby discovering his name. When she later guesses successfully, he is defeated not by the naming itself but by his anger at losing the deal (in his anger he tears himself in half according to some versions of the story).

“The queen will never win the game, for Rumpelstiltskin is my name!”

Rumpelstiltskin

The Rumpelstiltskin principle is a psychological phenomenon that can be summarized as “the magic of the right word” (Torrey 1972). That is, using the right word at the right time in a situation to achieve a desired outcome. In some cases, that may be addressing a person by name:

But it is worth the trouble [memorizing names]. Usually the first time I greet a student by name, especially outside of class, the student is astonished, as if witnessing some sort of miracle.

Actually, a sort of miracle does occur, because once I know a student’s name, we both tend to perceive our relationship as collaborative, rather than adversarial. The student works harder; I spend more time preparing; and we both enjoy the teaching and learning experience more.

Winston 2009

Written words in Judaism and Kabbalah

In most of Judaism, the proper name of God (the tetragrammaton YHWH, or “Yahweh” in English) is taboo to speak aloud. Consequently, God is referred to by several other names in many contexts, including Adonai (“my Lord”), Elohim (“God”), and Ha-Shem (“the Name”). Even among these periphrastic names, many (including Adonai and Elohim) are considered so sacred that they must not be erased once written. As a result, observant Jews usually avoid writing these names at all except in specific religious practices.

In Jewish thought, a name is not merely an arbitrary designation, a random combination of sounds. The name conveys the nature and essence of the thing named. It represents the history and reputation of the being named.

…

Because a name represents the reputation of the thing named, a name should be treated with the same respect as the thing’s reputation. For this reason, God’s Names, in all of their forms, are treated with enormous respect and reverence in Judaism.

Jewish Virtual Library

Interestingly, this appears not to apply to displaying names on a screen and then removing that name from the screen. The page from which I pulled the quote above contains a disclaimer at the top:

Please note: This page contains the Name of God. If you print it out, please treat it with appropriate respect.

Jewish Virtual Library

It is also apparently of no concern that the digital representation of the text (i.e. the data) is copied (downloaded) and later destroyed (deleted) by people viewing the page.

While names and words are important in Judaism, Kabbalism is a form of Jewish mysticism that puts particularly strong emphasis on the power of written language. Its central text is the Zohar.

Revealed more than 2,000 years ago, the Zohar is a spiritual text that explains the secrets of the Bible, the Universe and every aspect of life.

… It is a compendium of virtually all information pertaining to the universe—information that science is only beginning to verify today. Its vast and comprehensive commentary on biblical matters has captivated spiritual and intellectual giants for over two millennia.

But its codes, its metaphors, its cryptic language are not given to us purely for understanding. They are designed as channels for energy. Like all holy books, the Zohar is a text that not only expresses spiritual energy, it embodies it.

What is the Zohar?

To merely pick up the Zohar, to scan its Aramaic letters and allow in the energy that infuses them, is to experience what kabbalists have experienced for thousands of years: a powerful energy-giving instrument, a life-saving tool imbued with the ability to bring peace, protection, healing and fulfillment to those who possess it.

According to Kabbalism, simply owning or being in proximity to a copy of the Zohar grants blessings. For greater spiritual edification, one can scan the Aramaic letters of the Zohar (without understanding their meaning, similar to yantra or sacred shapes). Even greater blessings come with reading, studying or sharing it with others. It is considered appropriate for those who cannot read Aramaic to read a translation of the text. (See How to Use the Zohar.)

The Zohar used to be more of an esoteric text, with access to its contents reserved to the initiated. It is now disseminated widely, but it is still very much a mystical text. The idea is essentially that, when something is worded in a way that is vague or confusing, there is more room for interpretation, and therefore more depth. It can “answer questions” and so on more or less by making the reader make up the answer themselves. To quote my father quoting a friend of his from college (speaking about the Bible): The depth is within you. This is also an increasingly common interpretation of mystical practices like tarot and astrology: that is, it is a way of provoking someone’s mind to think about certain things, which can lead to genuine improvement. In other words, the Zohar may be genuinely helpful for reasons other than having supernatural powers. This is of course not the mainstream view within Kabbalism, since it is a form of religious practice.

Magic words and incantations

Double, double toil and trouble;

Macbeth, Act IV Scene I

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the cauldron boil and bake;

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg and owlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

Due to superstition and a few coincidental injuries, deaths, and other misfortunes, a belief arose within the theatrical community that Shakespeare’s play Macbeth was cursed (actors, like sailors, have historically been very superstitious). The idea was that Shakespeare used real spells in the play’s text, which either caused the play to become cursed directly or angered real witches who laid a curse on the play. As a result, it came to be believed that uttering the play’s title inside a theater (or possibly anywhere) is bad luck, and many people have referred to it as the Scottish play instead. (See also: my post Why do unlikely things happen? regarding coincidences.)

Among the oldest examples of curses are ancient Egyptian execration rituals, probably originating c. 3000-2500 BCE. These rituals changed over time and involved multiple different components, but one common practice was writing enemies’ names on pottery or other objects and then destroying or desecrating the object in some way.

ritual objects could be bound, smashed (red pots, probably with a pestle), stomped on, stabbed, cut, speared, spat on, locked in a box, burned, and saturated in urine, before (almost always) being buried (sometimes upside down).

Muhlestein 2008, p. 2

Magic words are not always used to curse. In regards to any kind of incantation or magic, very few individuals claim to have such power within themselves, since it is evident that humans do not go around using supernatural powers all the time. Instead, such language usually invokes a higher power, usually a god, ancestor, or other spiritual force. There is no real distinction therefore between incantation and prayer. For example, some Christians believe that reciting the Lord’s Prayer grants them protection, or that a Hail Mary grants them luck. Traditional mantras in Buddhism and Hinduism are often invocations of specific gods or spiritual forces. Many such prayers are regarded as functional when written as well as when recited verbally.

References

Feldman, T. P. (1974). Onomastic Concepts of “Bear” in Comparative Myth: Anglo-Saxon and Greek Literature. Literary Onomastics Studies 1(4).

Jewish Virtual Library. Jewish Concepts: The Name of God. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-name-of-god

Muhlenstein, K. (2008). Execration Ritual. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

National Football League (NFL). The Superbowl Rings. https://www.nfl.com/photos/the-super-bowl-rings-09000d5d82618287

Shakespeare, W. The Tragedie of Macbeth, first published 1623.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung (via the Met). Execration Text against the Nubians. Used in accordance with Fair use ee https://www.smb.museum/en/open-science/

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met). https://www.metmuseum.org

The State Hermitage Museum. https://www.hermitagemuseum.org

The Walters Art Museum. https://art.thewalters.org

The Zohar. Kabbalah Centre International, Inc. https://www.zohar.com

Torrey, E. F. (1972). What Western psychotherapists can learn from witchdoctors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 42(1), pp. 69–76.

Winston, P. H. (2009). The Rumpelstiltskin Principle. Slice of MIT. https://alum.mit.edu/slice/rumpelstiltskin-principle