While the title of this post might as well be a thesaurus entry, my purpose here is to investigate the differences between these concepts and how they operate in different contexts.

Mathematical equality

The reader is almost certainly very familiar with the equals sign or = used in math. Many of us first encounter it in statements like this:

2 + 2 = 4

This can instill the idea that “equals” refers to the result of a computation. It can be confusing for some students, therefore, when that idea turns out to be only partly accurate. This usually comes up when we begin learning about equations themselves rather than simply using equations in a specific application (for showing the result of a computation).

The more complete understanding of mathematical equality that is gained from this is generally something like “representing the same numerical value.” Often before algebra, we start seeing equations with a variable and learn to use a method of working backwards to ascertain the numerical value the variable must represent. These are called 1-step or 2-step equations. In such contexts the variable may even be written as a question mark or blank, though x is also common. When equations become more complicated, having the variable appear on both sides of the equals sign, we begin needing to know the properties of equality in more detail in order to use more sophisticated solving methods. For example, we learn that the so-called addition property of equality allows us to add the same quantity to both sides of an equation without fundamentally changing what the equation is saying. Equations at this point are often referred to in terms of “balance.”

The concept of an equation becomes more complicated when two variables are involved. The equation is still in a sense talking about having the same numerical value, but it’s not a single numerical value. Instead, an equation describes a relation between two quantities that could take on many different possible values. This relation is frequently that one variable is a function of the other variable (usually y is a function of x). Since it is useful in many situations to have the dependent variable alone on one side of the equation, we start seeing “y=” (and later “f(x)=”) as a special type of equation that is meant to be interpreted in a particular way (e.g. by graphing).

What is a function though, exactly? We generally refer to the dependent variable as “a function” as a kind of shorthand for “a function of x” (or whatever independent variable we’re dealing with). However, it’s not strictly true that the dependent variable is a function; it is a variable. If a function is a relationship between two variables, then perhaps it should be a kind of equation. But we know functions can be represented by any number of possible equations, for example the following equations all describe the exact same relationship between x and y:

y = 2x + 3

2x + 3 = y

x = (y-3)/2

3y + 1 = 6x + 10

Additionally, we learn in math class that a function could also be a graph, a table, or a set of ordered pairs. Now, most students are not terribly concerned with this question of what a function “really” is. In higher math, function is generally treated as a more descriptive, informal word referring to something that follows the law that each input has exactly one output. A function rule is any method we can follow to arrive at the output given a specific input. More formally, a function itself is identified with its graph Γ (Greek capital letter gamma). The graph is a set of ordered pairs, specifically a subset of the cartesian product of the domain and codomain (similar to “domain and range”). In fact, this is not only how functions are identified, but all relations for any number of variables.

Functions in this context are often referred to as maps or mappings and can be defined in several ways. A common way of defining a function here is to specify first the sets that are the domain and codomain and second the rule we can use to derive an output from an input:

f : A → B

f : a ↦ b

Relations generally, of course, are not defined this way, as they typically do not have a “direction.” Instead, we might define a relation denoted ~ by saying something like, “a~b if and only if…”

An important type of relation is an equivalence relation. Informally, an equivalence relation “behaves like” equality. An equivalence relation must have the following properties:

Reflexive: a~a for all a.

Symmetric: if a~b, then b~a for all a and b.

Transitive: if a~b and b~c, then a~c for all a, b, and c.

Equality itself is, of course, an equivalence relation. In math, it is a relation defined by being a subset of the cartesian product of any nonempty set with itself, consisting of those ordered pairs that have the same element in the first and second positions (i.e., = is the set consisting of anything that looks like (a, a) regardless of what a is). Technically, each set has its own “version” of equality, since an equivalence relation is defined for just one set.

In school math, the set in question is usually the real numbers or a subset of the real numbers (and sometimes but rarely the complex numbers). But since equality is defined the same way for any nonempty set, it easily generalizes to talking about, say, entire sets being equal. When speaking about things outside of math, “equal” tends to mean something different. When we say that two things are equal, this usually refers to something more like an equivalence relation: the two things have certain properties that are exactly the same, for example value, despite being distinct in other ways.

Logical identity and indistinguishability

So, speaking informally about things being the same could potentially mean a lot of different things. In logic and philosophy, the concept of “true” or “strict” equality is nailed down by the identity relation. Identity is the relationship an object has with itself and nothing else. In this context, no two things are “identical.” This concept is fundamental to many forms of logic and many big questions in philosophy, such as the persistence of personal identity over time. The question is this: are you the same person you were 10 years ago? Or when you were born? Or one second ago? And here, remember, by “the same” we mean identical in the strictest sense. Certainly our physical bodies change significantly over time, but are the physical constituents of your body what make you the person you are? If I lose or grow a skin cell, does that make me a different person?

A famous thought experiment regarding persistence of identity over time is the ship of Theseus. Theseus has a ship, identical only to itself, which is made of wood planks. Over time, planks occasionally get replaced. Normally, if a ship has a single plank replaced, we would still consider it to be the same ship. But what if, over time, all of the planks got replaced? Moreover, what if the ship’s original planks were saved after being replaced and reassembled back into the original ship? It would seem reasonable to say that if a ship is dismantled and then reassembled, it is still the same ship. However, our intuition cannot be correct on both accounts, because we now have two ships, one that is physically the original ship reassembled, and another that has been continuously called the ship of Theseus while having its pieces gradually replaced. No two objects are identical. Only one of these ships (at most) can possibly be identical to the ship that was initially named the ship of Theseus. Which one is the “real” ship of Theseus?

This is not really intended to be an answerable question. The point of the thought experiment is to show that we may have intuitions about identity over time that are in fact logically contradictory. As mentioned, philosophers are usually most interested in personal identity, with the ship just being an analogy. There are many proposed solutions. One is dualism, where a person is identified with a nonphysical soul that is eternal and does not change its constitution over time. Another is nihilism, where the person never existed in external reality at all and so questions of identity are just misplaced.

Another question in philosophy is whether two objects can be nonidentical without being distinguishable. That is, if there is literally no property by which we could tell two things apart, how can we really say they are distinct? A possible actual example of this is photons. Photons are not subject to the Pauli exclusion principle, a law of quantum mechanics that prohibits electrons (for example) having all the same properties occupying the same space. Much of the behavior of subatomic particles violates our intuitions about how objects work, however. Notably the so-called wave-particle duality is unlike anything we experience on a macroscopic scale.

Informally, of course, indistinguishable-in-practice is often what we mean by “identical.” The less distinguishable two objects are, the more likely we are to say that they are identical, even if we can actually distinguish them by, for example, their physical location not being exactly the same.

Resemblance and similarity

This appearance of sameness despite being obviously distinct is more properly called resemblance. Etymologically, the words resemble, similar, seem, same, and simile are all derived from the Latin simili, meaning similar. These words usually involve a judgment by a person about how and to what degree two things are alike. Similarity is often contextual, focusing only on features that are relevant to the present situation. If these features are clearly defined, similarity can often be measured mathematically.

For example, when using genetic sequencing to determine how closely related two organisms are, there are algorithms that can compute the percent difference between two genomes. However, even this requires human interpretation about similarity and difference. For example, if a segment of the DNA we’re comparing is CTGCA and CTGAA, it is relatively unambiguous that a single base pair has changed, and we would probably say the two segments are 80% similar. This number is the Hamming distance, or the number of individual substitutions to change one string of symbols into a different string of symbols. The situation becomes more complicated when we consider insertions and deletions (“indels”). Is the deletion of an entire segment of 15 base pairs counted as one difference or 15 differences? The answer is yes. Either way of measuring similarity works, but one or the other may be preferable in any specific case.

Additionally, there are complications regarding how to align two sequences for comparison. Since DNA change happens repeatedly over successive generations, comparing individuals that are not closely related may involve looking for changes on top of changes.

One alignment algorithm, for example, calculates an alignment score for a given alignment, then creates the best alignment it can by optimizing this score value.

When determining relatedness of extinct organisms we know from fossils but do not have DNA of, the comparison is usually morphological (looking at body features). In these cases, it is not possible to calculate a percent similarity, since the “total number of morphological features” is not well-defined. Nevertheless, it is possible to determine that an organism is more closely related to one thing than another. This can be used to classify organisms into nested hierarchies, providing evidence for shared ancestry.

Resemblance and forgery

An unusual type of resemblance is that of an object to a set of objects. Here, resemblance means something like the degree to which the object should be a member of the set. In forgeries of fine art paintings, while duplicates of actual paintings are sometimes produced, the more common strategy is to closely imitate a specific artist. When such a forgery goes on the market, it is difficult to determine whether or not it is genuine. There is no direct comparison that can be made, unlike when two objects are being compared for resemblance. Instead, the painting must be compared to the abstract idea of “the artist’s style.” Often, of course, forgeries are detected not by any artistic assessment, but rather through the determination that the paint or other materials used are too modern. Clues in the artwork as an image include ahistorical misuse of symbolism. If the forger is not an expert in the cultural and historical context of the real artist, they will often mistakenly and inappropriately combine or leave out important bits of symbolism.

It is possible that what is happening inside the forger’s brain is akin to the neural net of an image generation AI. These AI can make the same kinds of mistakes, combining or leaving out important features because they don’t “know” the context.

Can you spot a fake? When people claim to be able to identify AI images by sight, they are often unreliable. By that I don’t mean that they cannot do better than guessing at random. Many AI images can be easily identified as such with as much as a glance, however this is not true for all AI images, especially when the image is high quality but low resolution. Without using metadata or software, try to determine for yourself which of the following images were generated by AI:

Click here to show answers

Left column: 1. AI generated. 2. AI generated. 3. Photo by me. 4. AI generated. 5. Photo by me. 6. Switzerland Landscape #026 by LandscapeArtDF.

Right column: 1. Yellow Mountain by Yuan Zuo. 2. Black Abstraction by Georgia O’Keefe. 3. AI generated. 4. AI generated. 5. Painting by Bob Ross. 6. Surreal Landscape #5 by gogsiarcko.

Artists’ images are subject to copyright.

As with traditional art fraud, similarity to an original is one of the main reasons AI image generation is problematic. Unlike traditional art fraud, which mainly hurts art collectors, fraudulent AI generated images hurt currently working artists. AI images should never be presented as photographs or paintings because they are not photographs or paintings (even digital paintings).

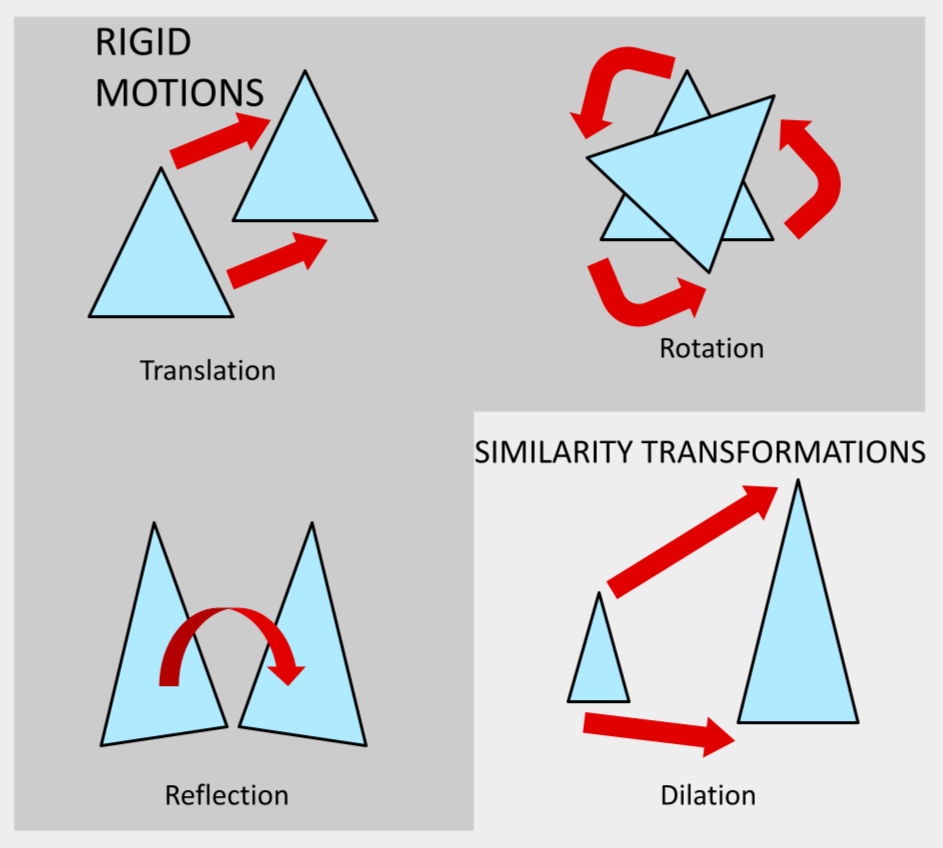

Geometrical similarity and congruence

Similarity is also a technical term in geometry. There, it refers to figures that have proportional dimensions and only differ by scale. In this context, a scale model of a building could be said to be (approximately) similar to the actual building. A map of a road is similar to the road itself.

Congruence is a related, stronger geometrical concept in which two figures differ only in position and orientation. In other words, two figures are congruent when they are similar with a scale ratio of 1:1.

These ideas are more properly described using transformations. A and B are congruent if and only if B is the image of A under a sequence of rigid motion transformations. Intuitively, rigid motions are geometrical transformations that do not squish, stretch, shrink, expand, or distort. Specifically, these transformations are translation, rotation, and reflection. Similarity transformations include all of these plus the transformation of dilation. A and B are similar if and only if B is the image of A under a sequence of similarity transformations.

Isomorphism and homomorphism

Isomorphism is a type of equivalence in math. In simple terms, it refers to structures being “mathematically the same” despite qualitative differences or details of how something is instantiated. In math, we often speak of structures being unique “up to isomorphism.” Any given structure we might want to talk about can generally be instantiated in infinitely many ways, each differing only in details we don’t care much about.

That being said, a pair of isomorphic structures can be qualitatively extremely different. Moreover, there are many cases in which it has been proven only that an isomorphic relationship exists, and it is not known exactly how two things are isomorphic.

Consider two algebraic structures, the first a set X with an operation * and the second a set Y with an operation ○. Formally, an isomorphism is a map (function) from X to Y with two properties: it preserves structure and it is a bijection. By preserving structure, we mean:

f(a * b) = f(a) ○ f(b)

For a and b in X.

By being a bijection, we mean that it is a one-to-one correspondence between the two sets.

Homomorphism is a similar kind of relationship but weaker than isomorphism: it need not be a bijection. Interestingly, isomorphism and homomorphism are, like congruence and similarity, defined in terms of how one structure can be mapped to (or transformed to) another structure. As with mathematical equality and equivalence, all these relationships are fundamentally defined as functions or relations.

Isomorphisms and homomorphisms generally apply to sets with discrete elements. In topology, there is a related concept of homeomorphism, which is a continuous reversible deformation, and diffeomorphism, a differentiable (i.e. “smooth”) homeomorphism.

Equality vs Equity (and justice)

Socioeconomically and politically, equality can mean a lot of different things. In the so-called Enlightenment which influenced American, French, and other revolutionaries, “equality” represented the fundamentally equal value of all human individuals (or all white men, as the case may be). At the time, when systems of nobility and monarchy dictated the social order, this was a radical idea.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Thomas Jefferson, The Declaration of Independence

Unfortunately, this is a naïve concept of equality among people, which does not translate unambiguously into social norms, public policies, and so on. There is wide agreement that many fundamental rights, such as freedom of association and freedom of travel, can be suspended in case of crime or imminent danger. There are also cases in which rights seem to be ambiguous with respect to certain situations. For example, if someone is censored on social media, is that a violation of their right to free speech, or is it the social media platform wielding their right to free speech? In other words, if one person writes something and asks another person to distribute that writing, and the person refuses, is this a use of free speech or a violation of it? Of course, the answer may seem very unambiguous to you, the reader, but keep in mind that this is a nontrivial and ongoing source of strife and dispute in American politics. If human rights were so obvious, we would not have so many books about them.

Later on from the Enlightenment, between 1896 and 1954, the doctrine of “separate but equal” was an outright lie. The idea of “equality” between Americans of different race has been contentious since before Jefferson. Since Brown v. the Board of Education in 1954, there has been a tremendous struggle to both assess and improve equality in education. It is from this struggle that we got the idea of “equal opportunity vs. equal outcomes.” Equal opportunity has the aim of creating a meritocracy, wherein people with the best natural character attributes achieve the most highly. A meritocracy, of course, is a system of inequality.

The argument for meritocracy is that individuals cannot be totally equal because they are not completely the same. Equal in “human dignity,” perhaps, but not equal in anything else. I think Americans latched onto this idea because individualism and meritocracy have always been part of the United States’ national ideology (the “American Dream”). The conclusion for many is that we should ignore unequal outcomes unless we can establish that they are due to unequal opportunity. However (and unfortunately), “opportunity” is not something that can be directly observed or measured. It depends on how much people are individually responsible for what happens in their lives.

The downsides of equality are often stated in terms like this: if you give each person in a group an apple, that’s equality. Some of the people don’t like apples though, so it’s not an ideal outcome. If instead you let each person choose between an apple or an orange based on their preference, the “market” will naturally optimize every individual’s happiness about the situation. Or, another example is asking a cat, a human, and a fish to climb a tree. The test is “equal” in that each is being asked to do the same task. Of course, fish cannot typically climb trees, humans can do so only with some difficulty, and cats are excellent climbers (the ranking may be reversed if the test was to get down from the tree).

So equity, then, is providing for people as different individuals according to their natural abilities. Equitable outcomes are not the same as equal outcomes. It is not an equitable solution for the cat to carry the fish up the tree in its mouth.

Nothing is the same as anything else

This blog post was partly inspired by a post by Kate Loves Math: The Limits of Mathematical Equality. I would like to pull out a few key ideas that are relevant here. First, Kate connects the idea of equality with uniformity and with proportionality. These are what people sometimes mean when they describe things being equal, but equality is properly a much stricter term.

The notion of equality in mathematics is way too restrictive. It’s just very uncommon that you’re going to find things that are actually equal, even when things are, in some very strong sense, the same.

Emily Riehl, as quoted by Kate

Equality is virtually as strict as philosophical identity, and nothing is identical to something other than itself. Identity is the way a thing relates to itself.

2+2 is not identical to 4. Taken one way, they are different merely because they are written differently. This is a simple example, but being able to write something differently is not trivial within math. Taken another way, 2+2 represents the image of 2 with itself under a binary operator, whereas 4 is just a number. 2+2 and 4 have equal numerical value, but they are not the same thing. Contrast this example with an equation like 2=2.

When considering two things that are the same but not identical, math often turns to the question of what would it take to get from here to there? This can’t be applied directly to humans or other organisms, which cannot be transformed into one another by any non-magical means. Individual persons, therefore, are irredeemably different. We may miss the big picture when we observe certain uniformities among groups of people. We would do well to focus instead on relations among people and how people relate to themselves.