Let’s talk about evolution.

All living organisms require a way to acquire and metabolize food, a way to respirate, and a way to reproduce. Many single-cell organisms like bacteria can eat by engulfing food within their cell, a process called phagocytosis. Algae and plants are autotrophic, meaning they produce their own food. Some simple animals, such as sponges, do not need to move in order to acquire food. Most animals, however, must actively seek out food. Being multicellular, getting food into the body is not quite as simple as engulfing it. Instead, this type of eating requires an orifice: a mouth. Expelling waste after eating likewise requires an orifice (an anus). This could be the same orifice. Jellyfish do not have a digestive tract that runs through their body; they take in food through their mouth, digest it, then “spit it back out” the way it came. This approach presents challenges for animals that must continually and even simultaneously eat, digest, and excrete. Instead, the more common body plan for animals is to have a digestive tract that runs from mouth to anus through the organism. These are typically on opposite ends of the organism to make the digestive tract as long as possible (to absorb more nutrients) and to avoid accidentally eating waste.

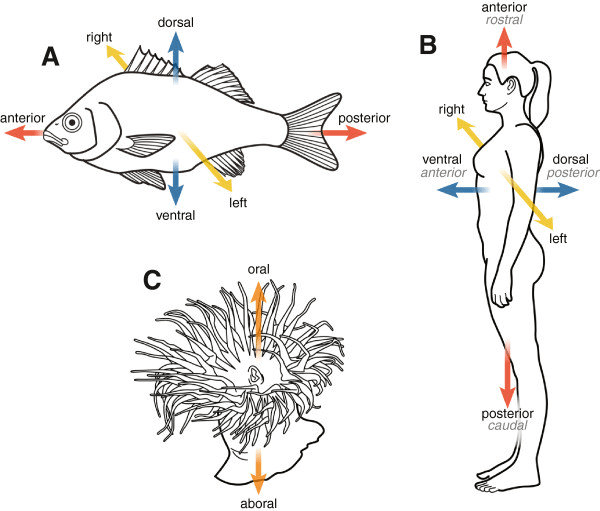

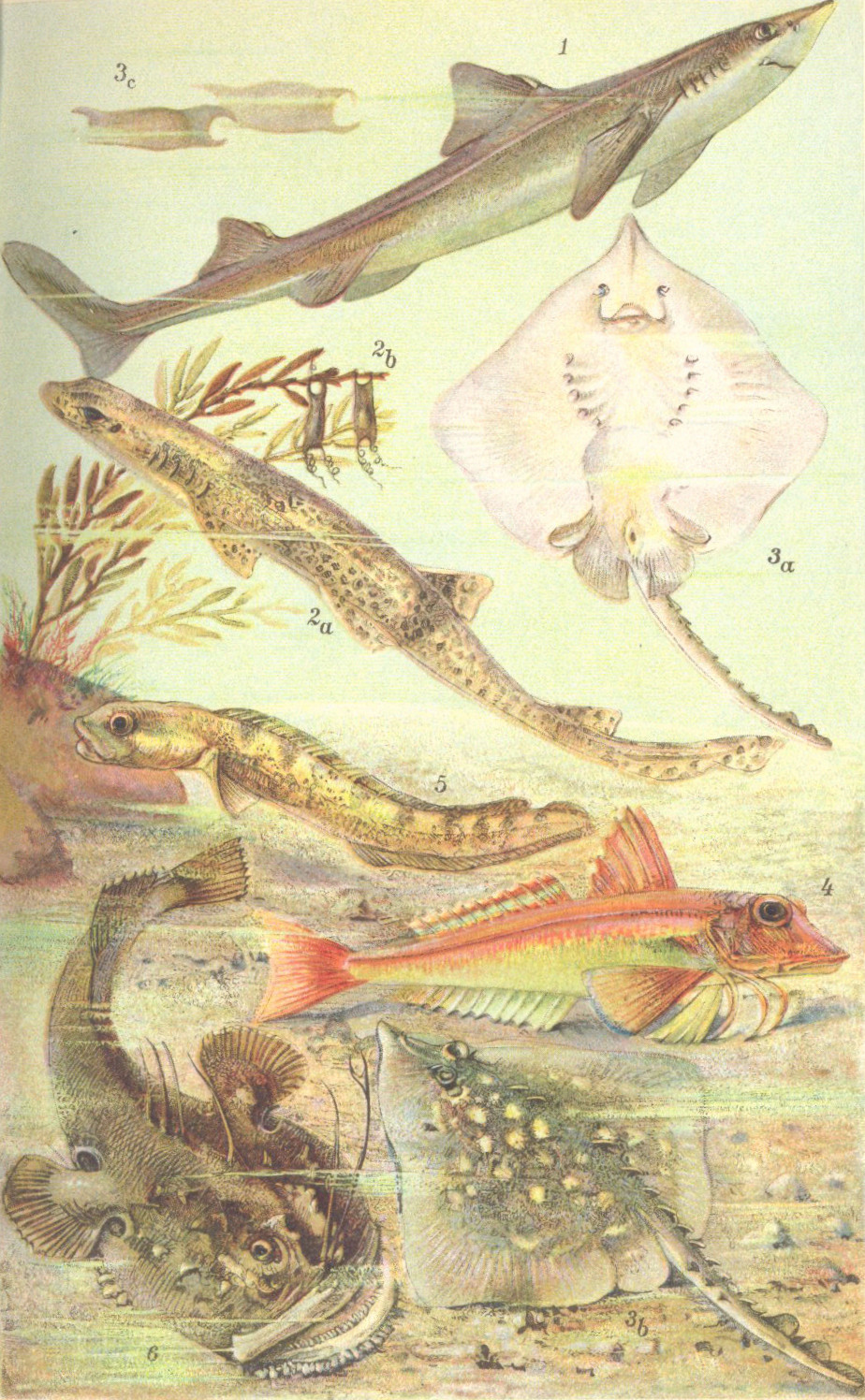

Imagine a very simple animal that has this type of digestive tract. It may resemble a worm. Geometrically, this introduces an axis, called the anteroposterior axis. A worm’s body plan is roughly symmetrical around this axis. It usually makes the most sense to move mouth-first, especially for predatory animals. We can establish a privileged direction on the anteroposterior axis which is forward, or towards the anterior, with the opposite direction being backward, or toward the posterior. By leading with the mouth, and needing the mouth to detect things that are edible, animals adapted to concentrate sensory nerves around the mouth. This was the beginning of encephalization, or the formation of a head.

Underground or in the deep open ocean, the environment is pretty similar in all directions. In a shallow sea, however, there is another identifiable axis with a privileged direction: namely, the vertical axis, with upward being towards the water’s surface (and sunlight) and downward being the opposite direction. In animals this is called the dorsoventral axis. If an animal is positioned so that the anteroposterior and dorsoventral axes are aligned (e.g. “upward” is “forward”), then it still makes sense geometrically to have a radially symmetrical body plan. This is more or less the case for the jellyfish. On the other hand, if the two axes are orthogonal (at right angles), then we can immediately identify a third axis which is orthogonal to both the first two. This is the limit of orthogonal axes that can be defined in three-dimensional space.

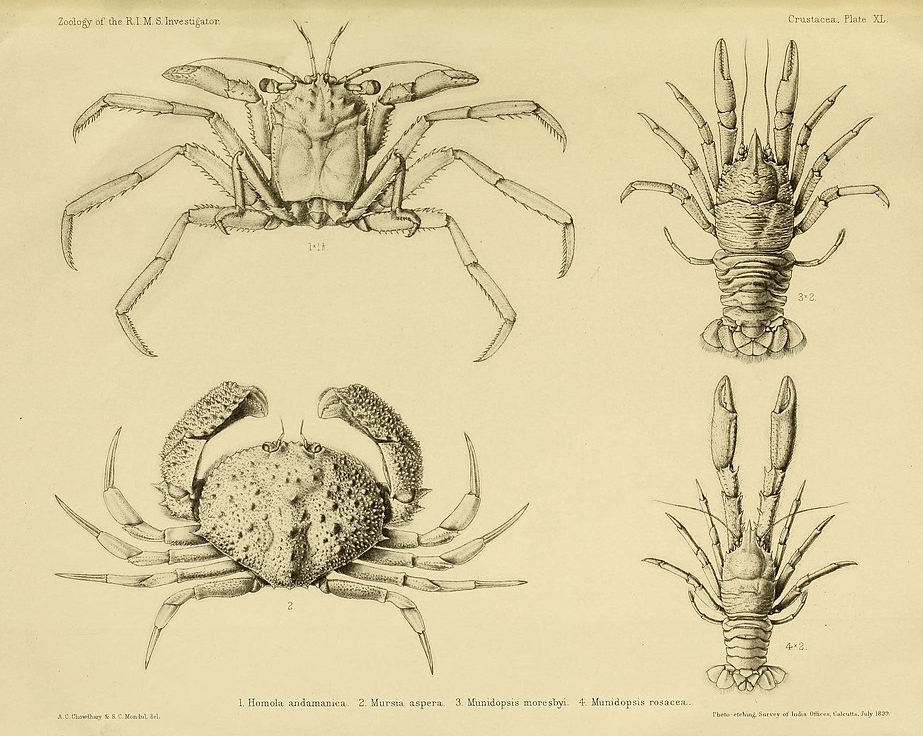

This third axis is the sagittal axis, running left-to-right. The first two axes have important differences between the two opposite directions each represents; forward is the direction of the mouth and upward is the direction of sunlight. However, the sagittal axis is merely a mathematical result of these first two, and there is no important distinction between leftward and rightward. This is precisely why fish and marine invertebrates such as trilobites are bilaterally symmetrical instead of being symmetrical in some other way. Left and right are the only directions in which the environment “looks the same,” so that is the way in which the animal looks the same.