In Part 1 and Part 2, we looked at some of the ways in which written languages have developed and creative ways in which they have been used. Here, we’ll look more into the interactions between languages and the relationship between language and speech.

Writing another language’s sounds

When two language communities come into contact, there is frequent need for speakers of one language to write down words from the other language, for example for bilingual dictionaries, loanwords, and names. If the two languages have different writing systems, then this requires transliteration or transcription, trying to spell a foreign word phonetically in your own script.

As we have seen in the previous parts, many alphabetic scripts are so closely related that they have letters that more or less correspond. The Latin letter A, for example, is very similar to the Greek letter alpha, the Hebrew letter aleph, the Arabic letter alif, the Cyrillic letter A, the Sanskrit letter अ, and so on. However, this can in some cases create more confusion when corresponding letters are not pronounced the same way. In such cases there may be two different ways to spell a word: either transliterated using the corresponding letters, or transcribed phonetically without regard for the original spelling. A word’s spelling could even be a combination of these.

English etymologies offer a wealth of examples. For one, loanwords that enter the language at different times will be transliterated differently depending on the current state of the language. Greek words that were adopted into Latin were transliterated into the ancient Latin alphabet, which initially did not include the letter G and rarely used the letter K, instead using C for both of these sounds. As a result, Greek words spelled with gamma (Γ) or kappa (Κ) were both spelled with the letter C (Smith 2016). Later, of course, the Latin letter C would come to sometimes be pronounced like /s/ in English. As a result we get words like governor and cybernetic, neither of which begins with a /k/ sound, both derived from Ancient Greek κυβερνήτης (kubernḗtēs). For similar reasons, you may see the Greek name of the famous mythological hero rendered as either Heracles or Herakles. (Wiktionary.)

Sometimes, the accepted spelling of a proper name or loanword will change to more accurately reflect the language of origin, but related terms will retain an archaic spelling. Such is the case with Kashmir (a region in the Himalayas) and cashmere (wool from the goats of the Kashmir region).

Case study: the transcription of Mandarin Chinese into English

Some spoken languages, including Mandarin, have a writing system that is non-phonetic. In other words, it’s possible for two people to write Chinese the exact same way but speak it completely differently (this only actually happens to a limited extent). As a result, there is no natural spelling coming from the original language to use in transliteration. Instead, words in spoken Mandarin must be transcribed into Latin letters (or other phonetic characters). Since English and Mandarin don’t have the same sounds, this leaves a lot of room for interpretation for the transcriber. Note that transcription into the Latin alphabet in particular is sometimes referred to as Romanization.

The word silk is possibly the oldest word of Chinese origin in English, in the sense that it derives from among the first loanwords from Mandarin’s ancestors to English’s ancestors. In other words, this was one of the first Chinese terms to be transliterated into an alphabet like the one we now use in English.

References to China first appeared in Greek literature around the 5th century [BCE], using the name Seres (Σῆρες) and Serica (Σηρική). Etymologically, Klaproth traces the word Serica to the Chinese character 丝 (si) for silk.

…

Posidonius of Rhodes (c. 135 BCE–c. 51 BCE) created a map (reconstructed by Petrus Bertius in 1630) that included “Seres” (the land of silk) and “Sinae” (literally the country of the Qin) for the first time, signifying that the Greeks had known about and/or had contact with China.

Solos 2021, pp. 149-150

The term silk came to English via the Latin sericus and the Old English seolc. Obviously, the ancient Greek seres is not a transliteration that closely approximates the pronunciation si. It is unknown whether the Greek word derived from Chinese through intermediary words or languages.

Systematic attempts to transcribe Chinese languages originated from Christian missionaries. From the 7th to 15th centuries CE there were occasional European missions to China, but little interest among these missionaries in studying Chinese language or culture (Camus 2007, p. 2). This began to change in the 16th century with Jesuit missionaries. The Jesuit approach to evangelism has historically had an anthropological and ethnographical character. Instead of attempting to totally override a culture’s belief system, the Jesuits attempt to incorporate Christianity into existing cultural structures. This (widely successful) strategy entails studying the local culture with a genuine aim of understanding the culture accurately. In other words, because Jesuits’ proto-anthropological work serves a functional purpose for them, they were disincentivized from creating religiously biased or misleading descriptions. (Ballano 2020.)

Evangelization can lose much of its force and effectiveness if it does not take into consideration the actual people to whom it is addressed and if it does not use their language, signs, and symbols.

…

[Moral prescriptions] must be responsive to the empirical situation to be effective and applicable to people in social practice. Thus, inculturation needs the scientific study of cultures by professional anthropologists to correctly insert the Christian faith to people’s behavior and cultural system. Misunderstanding the dynamics of culture can result in a misapplication of the Christian message and haphazard inculturation.

Ballano 2020, pp. 7-9

The Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci developed a Romanization of Chinese in order to produce bilingual dictionaries as part of a larger program to understand Chinese culture. However, this was not influential for later systems. The first widely adopted Romanization of Mandarin was the Wade-Giles system. This system was first developed by Thomas Francis Wade, a British ambassador and scholar of Chinese, in the mid-19th century CE. It was further refined by another Brit, Allen Herbert Giles. (Omniglot 2023a; Xing and Feng 2016, p. 100.)

Some context is required to understand why the British were interested in Chinese languages in the mid-19th century. In short: the Brits wanted their tea.

By the start of the 19th century, the trade in Chinese goods such as tea, silks and porcelain was extremely lucrative for British merchants. The problem was that the Chinese would not buy British products in return. They would only sell their goods in exchange for silver, and as a result large amounts of silver were leaving Britain.

In order to stop this, the East India Company and other British merchants began to smuggle Indian opium into China illegally, for which they demanded payment in silver. This was then used to buy tea and other goods. By 1839, opium sales to China paid for the entire tea trade.

National Army Museum

This began the first Opium War (1839-1842), when China attempted to put a stop to the smuggling. The influx of opium, and the consequences of losing to Britain, were devastating to Chinese society— so much so that Chinese historians traditionally divide the history of China into two parts, before the Opium War and after the Opium War. This also marks the beginning of the “Century of Humiliation” from 1839 to 1949, ending with the CCP’s victory in civil war (Kaufman 2010, p. 2).

The first Opium War ended in the Treaty of Nanjing (or Nanking) which forced China to open up to more British trading and influence. Previously, British merchants were only permitted to trade in Guangzhou or “Canton” (Encyclopedia Britannica 2018). Had that state of affairs continued, there may have been greater interest in systematically Romanizing the Cantonese language. However, the official language of imperial China was Beijing Mandarin, and this was (and continues to be) the language of government, law, academia, and so on. As a result, Mandarin was the obvious language of choice for British diplomats and scholars such as Wade and Giles.

The Wade-Giles system was widely used well into the 20th century. In 1958, the People’s Republic of China adopted a new system, Hanyu pinyin, which had been developed by Chinese scholars with the help of the Soviet Union. Pinyin is now the widely used standard for transcribing Mandarin, but some historical names and terms retain their Wade-Giles spelling. For example, Tao and Dao are different spellings of the same word, but Tao has been the preferred spelling for some despite being the older Wade-Giles version.

Other Romanizations of Chinese have been developed over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries as well, including the Yale Romanization and Gwoyeu Romatzyh, but mostly these never became widely adopted or were used for only a short time. Some have remained influential within specific regions or dialects, for example the Yale Romanization in Cantonese (Chik and Lam 2000; Kataoka 2024; Omniglot 2023b) and Gwoyeu Romatzyh in Taiwan (Omniglot 2023b; Xing and Feng 2016, p. 100).

| Romanization | Transcription of the same example sentence |

| Pinyin | Rénrén shēng ér zìyóu, zài zūnyán hé quánlì shàng yīlǜ píngděng. |

| Wade-Giles | Jen-jen sheng erh tzu-yu, tsai tsun-yen he ch’üan-li shang i-lü p’ing-teng. |

| Yale | Rén-rén shēng ér dz̀-yóu, dzài dzwūn-yán hé chywán-lì shàng yī-lyù píngděng. |

| Gwoyeu Romatzyh | Renren sheng erl tzyhyou, tzay tzuenyan her chyuanlih shanq iliuh pyngdeeng. |

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

We have seen that transliteration and transcription are fraught with inconsistencies and disagreements. Individual systems have pros and cons that often make them preferable to some group of people or another. When considering all languages and alphabets in the world, it is clear that such an ad hoc approach is insufficient for scientific purposes such as comparative linguistics.

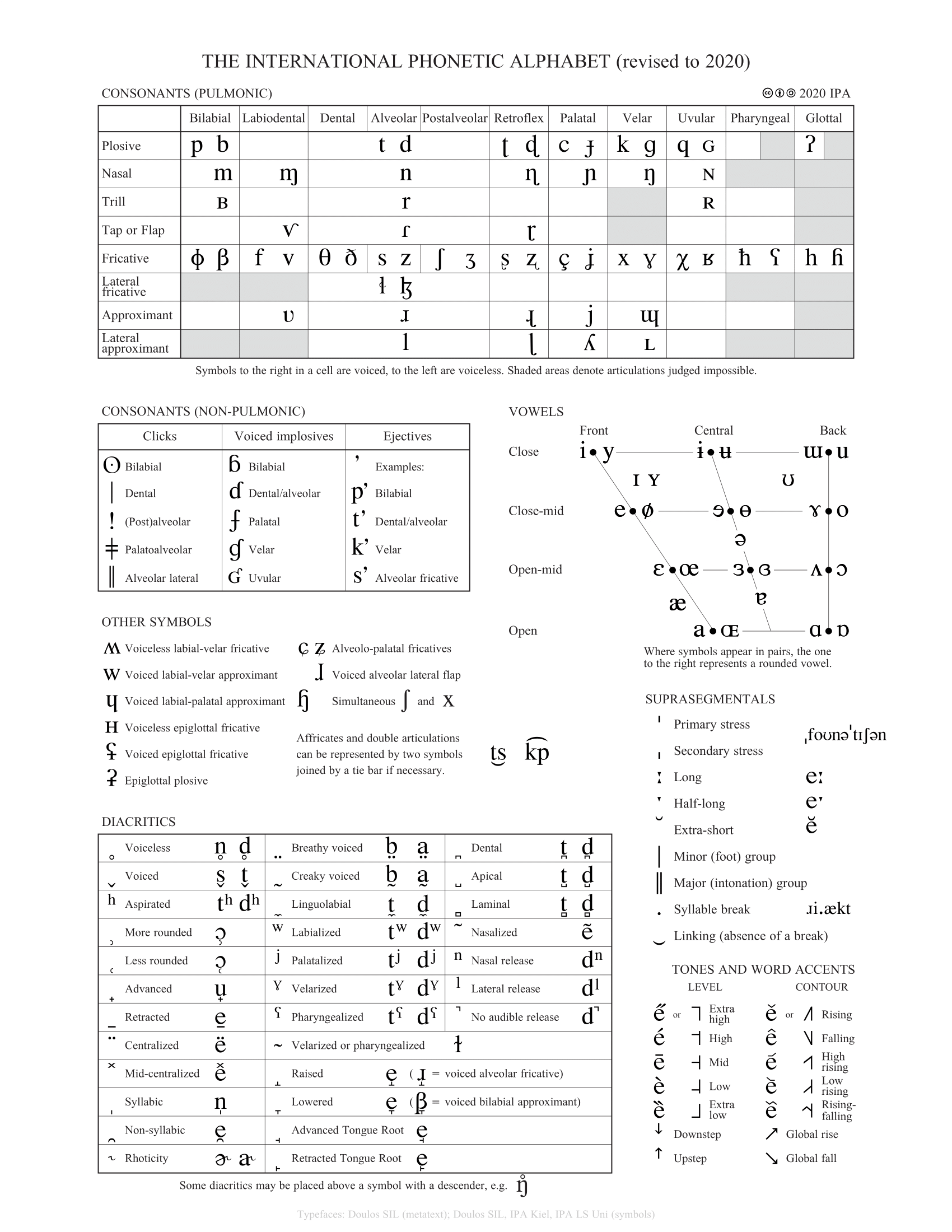

The IPA was developed to serve as a comprehensive, universal, objective transcription of phonemes. A phoneme is the smallest unit of vocalization that is capable of carrying meaning. It is similar to a single letter in an alphabet. The IPA generally divides phonemes into consonants and vowels. Consonants are categorized primarily by two features: where the sound is produced and how the sound is produced. They are additionally classified as voiced or unvoiced (whether the vocal folds or “vocal chords” are being engaged). For example, a voiced bilabial plosive consonant is produced with lips together (bilabial) and suddenly releasing air (plosive) while engaging the vocal folds (voiced) producing a /b/ sound. Vowels are categorized by the vertical position of the tongue (openness) and the horizontal position of the tongue (backness). Vowels are arranged on the chart to correspond approximately to the position of the tongue in the mouth when that vowel is produced. Vowels may additionally be rounded, meaning the sound is produced with the lips forming a circle or oval shape.

The idea behind the IPA is that it captures a very specific type of information, namely the semantically meaningful sounds of a language. In this way, it closely resembles phonetic alphabets of natural languages. The primary difference is that natural alphabets, unregulated as they are, don’t correspond one-to-one with phonemes. For example, the letter C in English may sound like /s/, /k/, /ch/, or /sh/ (e.g., ceiling, cat, ciao, coercion) and other letters can represent these sounds as well (e.g. sponge, kelp, treasure, vacation).

The full IPA chart is shown below. An interactive chart with sound recordings is available on the IPA website.

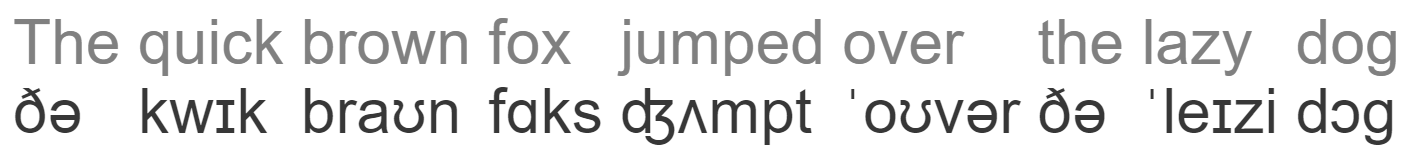

For example, here is an English sentence and its corresponding IPA transcription:

Note that in different dialects of English, the transcription will look different to account for differences in pronunciation.

The first incarnation of the IPA was published in 1888 in “The Phonetic Teacher” (Maître Phonétique). It was based on an earlier phonetic alphabet created in 1847 (Macmahon 1986, p. 36).

By the 1950s, the alphabet had developed near to its modern form, including diacritics and symbols for tone, stress, etc. (Udomkesmalee 2018).

The International Phonetic Association, which is responsible for the International Phonetic Alphabet (and confusingly also called IPA), has always been driven by two parallel areas of focus: practical language teaching and academic phonetics research. This union originated from language teachers’ desire to utilize phonetics in their teaching, a very modern approach in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One main purpose of the International Phonetic Association is the publication of a phonetics journal, now called the Journal of the International Phonetic Association or JIPA.

A random sample of just some of the many topics which have been published over the [Association’s first] 100 years shows something of the breadth of information within its covers: African languages, the anatomy and physiology of speech, basis of articulation, Bulgarian, Cardinal vowels, Caucasian languages, diaphones, dialect literature and folklore, the epiglottis, Eskimo, Finnish, Georgian, Gipsy, Hawaiian, the history of language, Ibo, Irish, Javanese, juncture, Kabardian, Kurdish, language standardization, Latvian, Macedo-Rumanian, morphology, narrow and wide, Ngarinyin, oriental languages, paralanguage, phonation types, rhythm, Ruthenian, Samoan, semantics, the Teachers’ Guild of Great Britain and Ireland, tongue twisters, Ukrainian, Visible Speech, Welsh, Wolof, Xhosa, Yiddish and Zulu.

Macmahon 1986, p. 35

Calques: an alternative to writing another language’s sounds

When a word or phrase needs to be used within a different language, it is not always transliterated. Sometimes it is translated, or rather calqued (made into a calque). Calquing involves translating a word or phrase literally in a piece-by-piece way. For example, the English term flea market is a calque of the French term marché aux puces, and the English term brainwashing is a calque of the Mandarin term xǐ nǎo. Similarly, the Finnish word koripallo calques the English word basketball, and the Hebrew kelev yam (seal, the animal) calques the German Seehund (literally “sea dog”). In some cases a word is calqued based on its etymology, and in some cases a calque is modified for clarity. An example of both is the Icelandic rafmagn, a calque of the English electricity. The raf part means amber, derived from the Greek root word elektron meaning amber. The magn part means power, which is descriptive and distinguishes the word from words relating to actual amber. (Wiktionary.)

Names and titles can also be calqued. The last king of Rome, called Tarquinius Superbus in Latin, is often referred to in English as Tarquin the Proud (History Skills). Many Native American names are calqued, for example Crazy Horse is a calque of the Lakota name Tasunke Witco (Crazy Horse Memorial). This practice inspired similar naming conventions in fiction, for example in The Elder Scrolls games many of the Argonian people (who are generally characterized as very foreign) have names like Only-He-Stands-There, implying a calque from the Argonian language (Bethesda Softworks 1999).

More calques in English include (in no particular order) with a grain of salt, time flies, slip of the tongue, common sense, and body politic from Latin; scorched earth, wood ear (mushroom), and paper tiger from Mandarin; near-death experience, chickpea, please, fourth wall, and ivory tower from French; mother lode, moment of truth, and blue blood from Spanish; uncanny valley and instant noodle from Japanese; thought experiment, loanword, and black market from German; firewater and medicine man from Ojibwe; masterpiece, uproar, and superconductor from Dutch; chopped liver, enough already, and go figure from Yiddish; bankrupt and slapstick from Italian; Iceland, Greenland, and Bluetooth from Old Norse; and abominable snowman from Tibetan. (Wiktionary.)

References and links

Ballano, V. (2020). Inculturation, Anthropology, and the Empirical Dimension of Evangelization. Religions 11(101).

Bethesda Softworks (1999). The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind.

Chik, H. M. and S. Y. Ng Lam (2000). Chinese-English Dictionary: Cantonese in Yale Romanization, Madarin in Pinyin. The Chinese University Press.

Crazy Horse Memorial. About Crazy Horse the Man. https://crazyhorsememorial.org/story/the-history/about-crazy-horse-the-man

Encyclopedia Britannica (2018). Treaty of Nanjing. https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Nanjing

History Skills. Tarquinius Superbus: the tyrannical last king of Rome. https://www.historyskills.com/classroom/ancient-history/tarquinius-superbus/

International Phonetic Association. https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org

Kataoka, S. (2024). Textbook Cantonese romanization systems. In Siu-Lun Lee (Ed.), The Learning and Teaching of Cantonese as a Second Language. Routledge.

Kaufman, A. A. (2010). The “Century of Humiliation,” Then and Now: Chinese Perceptions of the International Order. Pacific Focus 25(1), pp. 1–33.

Macmahon, M. K. C. (1986). The International Phonetic Association: The first 100 years. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 16, pp. 30-38.

National Army Museum. Opium War. https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/opium-war-1839-1842

Omniglot (2023a). Mandarin. https://www.omniglot.com/chinese/mandarin.htm

Omniglot (2023b). Comparison of Mandarin phonetic transcription systems. https://www.omniglot.com/chinese/mandarin_pts.htm

Smith, P. (2016). Transliteration and Latinization. In Greek and Latin Roots: Part II – Greek. University of Victoria. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/greeklatinroots2/chapter/§101-transliteration-and-latinization/

Solos, I. (2021). Early Interactions between the Hellenistic and Greco‑Roman World and the Chinese: The Ancient Afro‑Eurasian Routes in Medicine and the Transmission of Disease. Chinese Medicine and Culture 4(3), pp. 148-157.

Udomkesmalee, N. (2018). Historical charts of the International Phonetic Alphabet. International Phonetic Association. https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/IPAcharts/IPA_hist/IPA_hist_2018.html

Wiktionary. https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Wiktionary:Main_Page

Xing, H. and X. Feng (2016). The Romanization of Chinese Language. Review of Asian and Pacific Studies, 41, pp. 99-112. https://www.seikei.ac.jp/university/caps/assets/docs/journal/raps_no41.pdf