The following post is a critique of a particular class of worldviews and perspectives.

What is naïve realism and what do I mean by folk science?

Realism is a class of philosophical positions that assert the bona fide existence of certain objects, or that certain objects have certain discernible properties. The definition is vague because there are many different things one could be a realist about. For example, a realist on the philosophy of mathematics would hold that mathematical entities like numbers really exist, perhaps as transcendental abstract objects as in Platonism. An anti-realist would hold that mathematical entities like numbers are essentially fictitious or mere formalisms. Even when discussing a particular topic, such as mathematics, realism and anti-realism describe categories of philosophical positions, not individual positions themselves.

Naïve realism is a more all-encompassing view. It essentially states that external reality, in all regards, is more or less as it appears, and our senses give us direct access to external reality. Naïve realism works perfectly fine in most day-to-day situations. However, there are some people who adopt naïve realism as their worldview, choosing to reject ideas that seem to contradict their senses or intuition. I put flat earthers in this category. Virtually every flat earth argument appeals to naïve realism in some way. These include “the horizon looks flat” and “it doesn’t feel like we’re spinning.” I consider many young-earth creationist arguments to be similar. A common argument from creationists is mere incredulity at the idea of “one animal turning into another.” They are unwilling to accept any reality that is too unfamiliar to their personal experience in a kind of extreme naïve realism.

Folk science is a collection of traditional and intuitive knowledge and methods of inquiry (within a given culture). An example is folk psychology which is discussed in detail by Churchland, Dennett, and others. Folk psychology is the way humans tend to understand and talk about mental phenomena such as belief, desire, intention, hope, fear, etc. on a daily basis. This theory of mind predates modern psychology by a long way, and developed from an intuitive understanding of mental states and how they influence behavior. It is particularly useful as a way of understanding others’ minds and by extension a way of explaining and predicting others’ behavior.

I won’t be discussing folk science as a general topic, rather I will be focused on the content of (some of) today’s folk science(s). In particular, I’m interested in a class of worldviews in the United States that are based on a naïve realist interpretation of folk science. I will cover a few examples and discuss where some of these ideas came from, flaws with these models of reality, and social consequences of believing in them.

The origins of western thought

Mainstream science of today grew out of a tradition of “natural philosophy,” which arose in ancient Greece. It was further developed during the periods of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic Golden Age, and the Enlightenment before reaching its more or less modern state. Aristotle (384-322 BCE) is often regarded as starting this tradition with his Physics. For context, the name of this work comes from the Greek φῠ́σῐς (phúsis) meaning “nature.” This series of writings concerned a variety of topics including space, time, matter, causality, and motion. Aristotle also wrote about logic, cosmology, biology, human perception, ethics, and many other topics. He was a student of Plato, but the two took different approaches. Plato was concerned with the abstract concept of ideal forms, while Aristotle favored observation and deduction (a more scientific method by today’s standards). This difference is famously reflected in The School of Athens by Raphael.

Aristotle’s ideas were certainly not all original. He was influenced by Plato and the presocratic philosophers, as well as more generally by his cultural context. However, Aristotle was individually so influential that many ideas (or at least their prevalence) can be attributed to him. Among the least original of Aristotle’s theories was that of the classical elements. He proposed that the material world is made up of the elements of fire, earth, air, and water, while the celestial world is made up of the element of aether (the “fifth element” or quintessence). This was a typical understanding for his time and place.

On the more original side, Aristotle was one of the first known creators of a taxonomic categorization system for living things. This was a hierarchical system based on observations of morphology (the shapes of body parts), much like later systems. However, later systems benefited from having a much larger number of careful, detailed observations documented. Aristotle correctly identified that aquatic mammals and fish are in different categories, but he failed to identify that aquatic mammals and land mammals should be in the same category.

Another important idea attributed to Aristotle is the five senses: touch, sight, smell, taste, and hearing. Also important but much more abstract are Aristotle’s ideas on cosmology and teleology. Aristotle’s cosmology and taxonomic system influenced the creation of a medieval Christian concept known as the “great chain of being.” This is a hierarchical model of cosmology that arranges all things, living and nonliving, according to their level of perfection. God is at the top followed by angels, humans, mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, various “lower” animals, followed by plants and then minerals.

Aristotle analyzed the nature of cause and effect and described four causes that constitute every object: material, formal, efficient, and final. Essentially, each of these answers a specific type of “why” question with a “because …” answer.

- Material cause has to do with the physical properties of the matter constituting an object.

- “Why did the chair catch fire so easily?” “Because it was made of wood.”

- Formal cause comes from the abstract form, concept, or design of an object.

- “Why can a ball balance on a chair?” “Because chairs have seats which are a relatively flat surface.”

- Efficient cause is transformation resulting from the action of an agent.

- “Why is the chair broken?” “Because Edgar smashed it.”

- Final cause is the purpose or intended function of an object.

- “Why are there chairs in the sitting room?” “Because chairs provide a place to sit.”

This is a massive simplification, but basically these are ways of explaining the chair’s nature. Without going into too much detail about this theory, it is the final cause or telos that I wish to focus on. Telos may alternatively be translated as purpose, reason, or end (as in “the ends justify the means,” not “the end of the world”). This idea spawned the philosophical study of teleology. This is one of many -ologies in philosophy, like ontology (the study of existence) and epistemology (the study of knowledge). These are often discussed with respect to a particular topic. For example, we can talk about epistemology generally, but there is also epistemology of mathematics, social epistemologies, and so on.

Folk biology

After Aristotle, the next major taxonomic work in the west was from Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778 CE). Linnaeus is regarded as the father of modern taxonomy and his work is still influential. He invented the hierarchical system of kingdom, class, order, genus, and species (phylum and family were added later) and the system of binomial nomenclature. This is the naming of organisms by their genus and species, like Homo sapiens or Tyrannosaurus rex. Linnaeus’ three kingdoms were animals, plants (or rather “vegetables”), and minerals. He grouped organisms together based on their morphological similarity, and much of his original system remains in our classification of organisms to this day. However, observations of morphological similarity have limited reliability, given that it boils down to an assessment that one thing “looks like” another thing. Refinements of the taxonomic system post-Linnaeus benefited from more observations of different kinds of organisms, understanding evolution, paleontological finds, the discovery of DNA and the development of genetic sequencing, and so on.

By the time of Linnaeus, the idea of species was well established but not concretely defined. Linnaeus himself was a creationist and did not believe that species were related. Charles Darwin (1809-1882 CE) in his book On the Origin of Species attempted to explain why there are so many different species and why species are the way they are. Namely, that explanation is evolution by natural selection. Darwin’s picture of evolution is roughly as follows:

- Within a population, there is natural variation in individual characteristics.

- (Some of) this variation is heritable from parent to child.

- Some variations are beneficial to the individual’s survival, some are harmful, and most are neutral.

- In a competitive environment with scarce resources, individuals with beneficial variations are more likely to survive and produce offspring and individuals with harmful variations are less likely to do the same.

- Over time, small variations accumulate and result in speciation (organisms becoming different enough to be considered separate species).

- Hypothetically, this process has been taking place for a long time, and if it does explain the existence of different species then it implies that all organisms had a common ancestor.

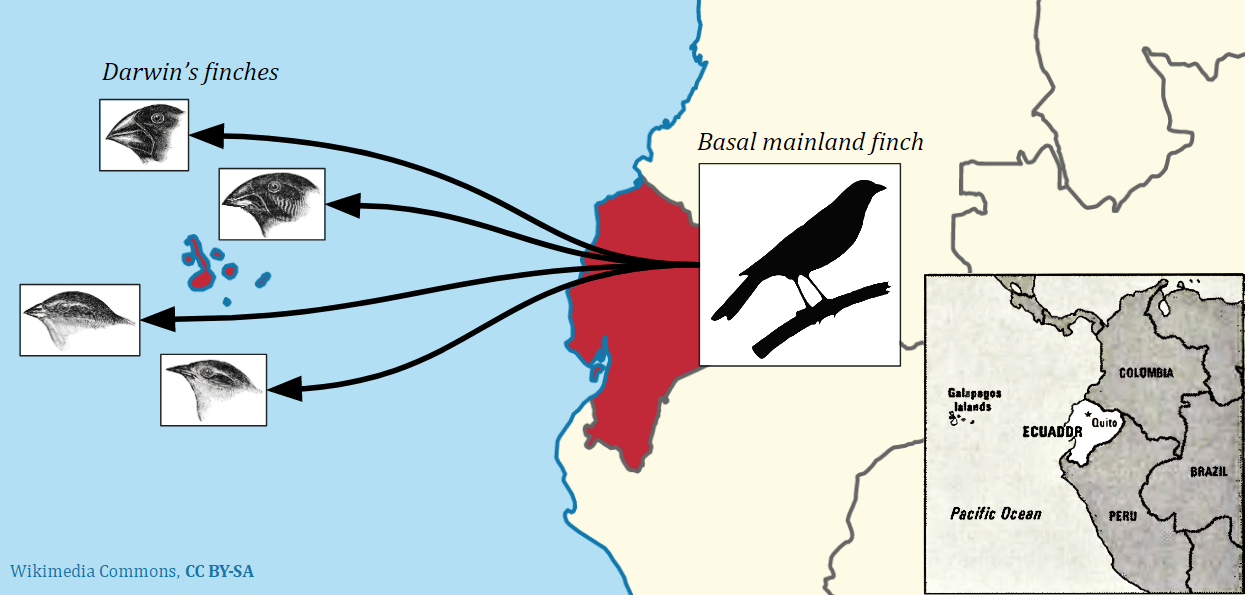

The prototypical example is the evolution of the finches of the Galapagos Islands. A single species of mainland finch migrated to the Galapagos, forming a distinct population on each island. Unable to find the seeds they liked to eat on the mainland, the finches found food wherever they could. The remarkably different ecosystems of each island yielded different opportunities for the birds. Some ate insects, some ate fruit, some ate leaves, and so on. Over time, natural selection shaped the beaks of each population to whatever shape is most efficient for their specific food source. Each island evolved its own unique species of finch.

Species: I’ve been using this term a lot, so what is a species? I was taught in high school biology that organisms are the same species if they can produce fertile offspring. However, some reflection reveals that that definition can’t possibly be comprehensive, because there are many species of asexual organisms. As it turns out, “species” is not a perfect concept– nor is it a single concept. What I was taught is known as the “biological species concept,” one commonly used definition, but there are over 20 alternative species concepts used in biological and taxonomic literature. Thinking about the fact that speciation occurs gradually over time, it’s obvious that relatedness of any two organisms is a spectrum. It’s generally accepted within biology now that species are not natural kinds, they are just labels given by humans for human purposes.

In fact, this is not just a species problem. Similar issues exist at every level of the taxonomic hierarchy. It is for that reason that modern biology tends to focus on phylogeny and cladistics (lines of descent) rather than the traditional taxonomy. This is not new, it has been mainstream for at least 50 years. It’s why, for example, we say that birds are dinosaurs: the clade dinosauria is defined as all the descendants of the most recent common ancestor of ornithischian dinosaurs and saurischian dinosaurs. So whatever birds might possibly evolve into in the future, their descendants will always be dinosaurs. They will always be birds as well. This is the law of monophyly: essentially, as time goes on, we would hypothetically have to keep adding more and more specific labels as species diverge through evolution. Linnaeus and his contemporaries saw taxonomy as a classification of a static system within nature, and recognizing it as an ongoing space of change is a paradigm shift.

Now, many times cladistics reaffirms the traditional taxonomy. Many classical categories, like rodents, are (more or less) clades. We may have to move a genus or two, like removing rabbits from rodents. Other times, it causes real difficulty. Suppose we want to say that there is a category of animals that are “fish.” There are two different kinds of boney fish morphologically, ray-finned fishes and lobe-finned fishes. For example, a sea bass is a ray-finned fish and a coelacanth is a lobe-finned fish. But since tetrapods (i.e. mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and birds) all evolved from lobe-finned fish, any “fish” clade that includes both sea bass and coelacanths would also include humans, chickens, turtles, and so on. Another way of saying this is that coelacanths and humans are more similar to each other than either one is to a sea bass. We are obligated to pick one of the following options:

- Say “fish” includes the clade of lobe-finned fishes. In that case humans and other land mammals, reptiles, birds, etc. are fish. This seems undesirable.

- Say “fish” excludes the clade of lobe-finned fishes. In that case many animals we would ordinarily want to call fish are not fish, like coelacanths and lungfish. This would cause confusion.

- Say “fish” includes animals that look like fish regardless of their phylogeny (ancestry). This is similarly unscientific (although less extreme) to considering whales to be fish. Such a category may be useful for some purposes (such as angling), but not generally for science.

- Discard “fish” as a legitimate category of animals. This is the eliminativist approach. Many of Linnaeus’ original taxa are no longer used, like vermes (“worms”) which included such animals as tapeworms, slugs, barnacles, squid, jellyfish, coral, and earthworms. Since “fish” is a much more basic category, preceding Linnaeus by thousands of years, it might be more difficult to give up.

The typical American folk taxonomy is strongly influenced by Linnaeus’ system and by the naïve realist approach of distinguishing organisms by appearances. This generally works fine but can cause a few problems. First, this perspective tends to view the biosphere as being static, either ignoring evolution or thinking of it as something that happened in the past. Ecological consequences such as extinction, therefore, might not be in the forefront of people’s minds. Second, adherents to this view may be confused about certain animals being called “higher” or “lower” and may interpret this as “more evolved” or “less evolved.” This can result in a number of misunderstandings about humans and animals.

Folk theories of evolution

Most people have a more or less Darwinian picture, but evolution is a very widely misunderstood theory. This is where teleology comes in: one of the most significant misinterpretations of evolution is that it has a teleological end goal. This is known as orthogenesis, the theory that evolution consists of a series of progressive improvements. The phrase “survival of the fittest” is often interpreted to mean “survival of the best” in a general sense, but it really means “survival of the best adapted to the present environment.” Organisms do not become “better” over time, nor do they always become more complex over time. Additionally, contemporary organisms can never be “more evolved” or “less evolved” than each other. All organisms have been evolving for the same amount of time. Chimpanzees are not primitive animals compared to humans, nor are crocodiles primitive because they have not significantly changed their morphology in millions of years, and so on. Instead, we can refer to individual morphological structures as being “more basal” or “less basal.” Basal means a trait has been preserved by evolution in a population. In order to maintain a trait, it has to be continually selected for, so whatever traits a population has are those that are most adaptive. Compared to chimpanzees, for example, humans have some traits that are more basal, such as relative thumb length, and some traits that are less basal, such as brain size. (See Almécija, S., Smaers, J. & Jungers, W. The evolution of human and ape hand proportions. Nat Commun 6, 7717 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8717)

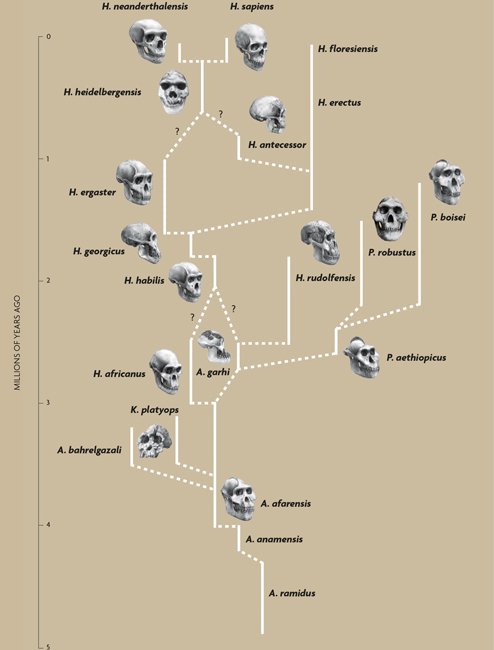

Another misconception about evolution is that it is linear, as in one type of animal evolves into another type of animal which evolves into another type of animal and so on. In reality, following population genetics over time is much more complex. For example, a population could split, evolve into different species, then come back together and hybridize into a single species. If that seems like an odd example, note that Homo sapiens hybridized with Homo neanderthalensis in prehistoric Europe. This had a very small effect on the human genome as a whole, but hypothetically if a population of hybrid humans was isolated from other members of genus Homo, they could have evolved into a distinct species.

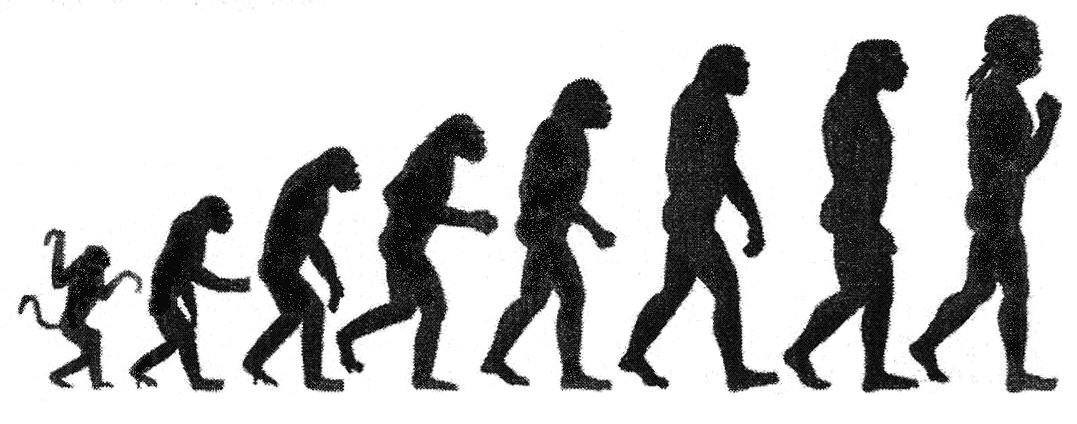

Both orthogenesis and linearity were promoted in public consciousness by the famous illustration The March of Progress depicting 25 million years of human evolution.

Among other things, this illustration obscures the fact that many of these species overlapped in time and it ignores all our close relatives beyond our direct ancestors.

The idea of linear orthogenic human evolution is especially important because it makes room for the idea that humans are special among animals. Biologically, there is nothing to distinguish humans from any other organism on the earth (except to the extent that we can distinguish any organism from any other). American folk science places humans at the pinnacle of evolutionary perfection, often making a distinction between humans and all other kinds of living things. In other words, a believer in this view would say “humans and animals,” not “humans and other animals.” This tends to engender specism and deemphasize animal welfare and the health of the ecosystem.

As a matter of pure speculation, this belief system could in part be a way for people to rationalize their participation in systems that are harmful to animals and the environment. Americans want to eat meat and have air conditioning, but don’t want to feel guilt or cognitive dissonance over the consequences of these decisions.

Straight up denial of evolution is also a common view in the US. In recent decades, the number of people who believe humans were created in their current form has hovered around 40% of the population (Gallup 2019). This requires such a profound rejection of scientific evidence that it opens the door to essentially any belief that is unsupported by evidence, such as antivax theories. While American folk science typically entails some degree of ignorance or misunderstanding of mainstream science, it ascribes a general reliability to scientific discoveries. The religious creationist view rejects science totally. I say this because, in order to deny evolution, one must deny the reliability of commonly used scientific tools and methods including radiometric dating and and genetic sequencing. This is despite the fact that these are now indispensable to industries such as mining and agriculture.

That said, I don’t personally consider evolution denial to be the American folk science perspective. It is concerning, however, that these two groups have a quite similar understanding of what evolution means. The typical folk scientist does not understand evolution but does trust the scientific consensus that evolution is accurate.

Folk theories of perception

As I mentioned, American folk science takes a naïve realist stance towards most things. This is particularly important when considering the mechanisms of human perception, since naïve realism posits that sensory perception gives a kind of direct access to reality. The folk theory of perception is based on Aristotle’s five senses. There are a few ways in which this picture is inaccurate or incomplete.

First, let’s discuss errors of perception, which I will broadly call illusions. Most people understand the idea of an optical illusion or a magic trick, types of illusions that are familiar in everyday life. Without necessarily understanding exactly how it works, they are aware that their perception is being misled. People are also familiar with simple misperception, for example occasionally mishearing a word when distracted. In other words, the naïve realist does not generally believe their perception to be infallible, and they understand some specific ways in which it can fail. Rather, the naïve realist distinguishes illusions (which are special cases) from “ordinary perception,” and posits that ordinary perception still works to provide an overall accurate depiction of reality.

Let’s consider one of the five senses: sight. The folk scientist understands this phenomenon to be quite complex. They are likely aware of color blindness, binocular depth perception, pupils adjusting to light or dark, peripheral vision, focus and conditions that affect focus requiring corrective lenses, certain types of optical illusions, and so on. They may additionally be aware of more details about the mechanisms of eyesight, such as the existence of rods and cones and their relationship to color vision, the fact that the image projected onto the inside of the eye is upside down and must be flipped by the brain, the small blind spot caused by the optic nerve, and so on.

In my estimation, the folk scientist is most likely to miss the importance of visual processing in the brain. Processed visual information is complex and not at all like streaming video (which is how some think of it). This is due to a few factors. Generally speaking, these factors are adaptations to use visual information as efficiently as possible. One example is filtering incoming information through attention. This causes what is known as inattentional blindness. Even though the eyes are capturing visual information and transmitting that information through the optic nerve, the brain simply discards information it deems unimportant. Certain objects within the visual field are not present within visual perception. The brain also processes different aspects of vision separately so that it’s possible to make sense of what we’re seeing, for example detecting faces or detecting movement.

Other senses

Some consideration reveals that the classical five senses are not comprehensive in describing sense perception. For example, humans have a sense of balance that is constructed from information from multiple sources. This includes fluid in the inner ear, visual information, and pressure (forces) of various parts of the body. When these sources of information disagree, or when information is missing, it can cause dizziness, vertigo, disorientation, and nausea. Humans also have a somewhat related sense called proprioception, which is the sense of limb position and body movement. This information also comes from multiple sources, including pressure and visual clues.

I can imagine an argument that these are “complex” senses, while the classical five sense are the basic sources of information. This is an inaccurate characterization of the five senses, however. Let’s consider what the basic sources of information actually are: the different types of sensory neurons in the body. These are called receptors. There are chemoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, nociceptors, photoreceptors, proprioceptors, and thermoreceptors. Vision is the one sense that can be defined solely by the type of receptor cell involved: photoreceptors appear only in our eyes and vision does not rely significantly on any other type of receptor. Otherwise, different types of receptors appear throughout the body, and the information from them is interpreted differently in the brain. Both taste and smell use chemoreceptors, but they are classically considered distinct due to being detected by different organs. Mechanoreceptors and thermoreceptors in different parts of the body can either produce tactile sensations (touch) or visceral sensations (hunger, indigestion, the need to urinate or defecate, and so on).

Again, the result is that the folk science is inconsistent (not well defined). If “a sense” is a high-level mode of perception with complex features, then it must include things like proprioception. On the other hand, if “a sense” corresponds to a particular type of sensory receptor, then taste and smell should both be subsumed under the sense of chemoreception. It seems clear to me that the former makes more sense based on our intuitive understanding of different kinds of sensations. Aristotle simply didn’t consider or wasn’t aware of the full variety of sensory data our bodies provide to our brains.

Why senses matter

There are many physical conditions which can impede the functioning of human sensory perception. This includes damage to the central nervous system and damage to sensory organs. Two major types of disability, blindness and deafness/hardness of hearing, are understood within folk science as a lack or major impairment of the sense of sight or hearing, respectively. This is partially accurate, as blindness is an impairment of sight and deafness/hardness of hearing is an impairment of hearing. However, the folk science perspective is (of course) overly naïve. To the folk scientist, the term “blind” usually means totally without sight, as in for example someone who is missing the optic nerve connection, and similarly for deafness.

In reality, this kind of total blindness or total deafness is rare. These conditions are not black and white, but rather each is a (multidimensional) spectrum of physical capability. There are different ways in which a person can be blind, such that two people might have very different sight but it would be impossible to say one is able to see better or worse than the other. Moreover, even two individuals with the exact same physiological circumstances will have vastly different experiences in their lives. As the saying goes, “If you know a ______ person, then you know one ______ person” (insert any category whatsoever).

By failing to understand the complexity of their own experience, the folk scientist precludes themselves from understanding the true diversity of experience that exists within humankind. That in turn prevents properly showing empathy to all people. It is an ableist and chauvinistic perspective.

What folk biology says about sex and gender

At its most naïve, the view is that sex and gender are the same thing and an immutable binary. This is often used as a cudgel against transgender people. I addressed this in detail in my post An analysis of biological arguments against transgenderism. However, there are some more specific reasons why the naïve view is flawed. As with senses, it comes down to “biological sex” not being well-defined as characterized. There are several things people point to in defining sex, including genitalia, chromosomes, and so on. The problem is that these several ways of defining sex don’t agree in all cases, revealing that sex is defined in reality by a cluster of properties. This means that our understanding of biological sex admits vagueness, ambiguity, and exceptions. Fundamentally, biological sex is a construct as much as as gender is, though they are different phenomena and serve different purposes. The traditional sex binary is a simplification that is useful in describing broad patterns in morphology and reproductive behavior. It is not a universal. Modern medicine and physiology has a more sophisticated understanding of the normal variation in human reproductive systems, hormones, and so on.

The sex-gender distinction itself is, as I see it, a misleadingly semantic issue. It doesn’t ultimately matter what these concepts are called, so the mere argument that these words mean the same thing is moot. The issue underlying the refusal to accept this distinction is a denial that a person’s sex and gender could possibly be “mismatched” according to their paradigm. This has the unfortunate side effect of preventing such people from understanding gender in other cultures, which can in turn be incorporated into xenophobia and nationalism.

Folk linguistics

I attribute American folk theories of language to the way English has traditionally been taught. This in turn originated from grammar education in England. The basic theory is this:

- A language consists of words and grammatical rules.

- A word consists of a spelling, a pronunciation, a definition (meaning) and part of speech.

- Grammatical rules describe how parts of speech can be combined to form sentences.

Once again, we see that the folk theory is vaguely accurate but missing a lot of detail and nuance. For one, the idea of “grammatical rules” glosses over the complexity of English usage. It is not possible to list all the grammatical rules, in part because grammar is so extremely flexible and context-dependent. Contrary to folk linguistics, a comprehensible sentence is not generally ungrammatical. “Ungrammatical” refers to a misuse of language that produces something unintelligible, like *turn really never goose green went ate run. Those are all meaningful words, but those words put together in that order fails to create a sentence (note that an asterisk preceding a word or sentence is traditionally used to indicate an ungrammatical example.)

There is a similar contradiction in saying that something is “not a word.” Any word that is successfully being used to convey a meaning is a real word, regardless of its provenance. Compare that to, for example, *hjjfjkhjkfh, which actually is not a word. Part of the reason for this confusion comes from a misunderstanding about what “a language” is.

A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.

Max Weinreich

Just like with organisms, and for similar reasons, languages exist in nested hierarchies. Regional dialects are well known, but any community of speakers has its own patterns, and every individual has their own idiolect, which is fluid and changes over time and depending on context. Most people are members of multiple communities and use language differently in each. What folk scientists would consider “correct” English is more properly called “standard” English. It is a particular version of the language that has been privileged through its inclusion in education, law, and so on. However, despite this privileged status, it is not more logical, structured, sophisticated, or advanced than any other dialect of English. If it has a useful purpose, it is merely to create a standardized mode of communication to facilitate understanding of legal processes etc.

So in general, a sentence being ungrammatical or a word not being a word are usually in relation to “standard” English. There is a sense among many folk scientists that deviation from this particular dialect represents a kind of degeneration into verbal chaos. This is, as I think of it, the ideology of a 20th century high school English teacher. It is not so much a misunderstanding as it is people accurately understanding an inaccurate thing they were taught. Full-blown realism regarding the correctness of “standard” English specifically as it exists today is the extreme of this view.

It is important as a general rule in communication to consider your audience. A concern with using “nonstandard” English is that people outside your community may not understand it, but that may or may not be desirable in any given case. I see no other non-chauvinistic justification for enforcing “correct” grammar. Depending on the situation, the dismissal of another dialect as ungrammatical may be motivated at least in part by racism, classism, and nationalism.

The flexibility of language is underappreciated in my opinion. Communities of speakers can form distinct speaking styles rapidly, especially when navigating a novel challenge. New words naturally arise as needed and grammar can be adapted to express more nuanced meaning. It’s also important to note that speaking to someone in person is more complex than written language, incorporating both words, prosodic features like tone and emphasis, facial expression and body language, etc. Because words can be augmented in this way, words have much more flexibility. For example, it is widely known that sarcasm is difficult to convey over text. That meaning is essentially restricted to verbal communication (there is an imperfect solution using /s, but the point stands).

Final thoughts

Summary

In general, what I call America folk science consists of theories that are partially accurate but oversimplifying. The immediate sources of these theories is mainstream education, religion, and culture. Problems rarely come from an outright denial of scientific consensus (except in special cases), but rather they come from naïve mis- or outdated understanding. American folk science is characterized by black-and-white thinking, an uncritical realism about categories in scientific theories, and an overall confidence in the scientific process.

Is the folk scientist a strawman?

The prototypical American folk scientist I describe in this post is not meant to represent an individual person. It is a convenient way of referring to a collection of ideas that some people believe. No one necessarily believes all these things, or believes them in precisely the way I describe. I make no claims as to the statistical prevalence of any of these ideas, except where specifically stated and sourced. This post is meant to address the ideas themselves.

A comment on the term “American”

I am aware that there are many outside the United States who consider themselves American. There are also Native people within the United States who identify with the label. The ideas discussed are not limited to the US, but are characteristic of colonizer cultures. I choose to use the term American, derived from an Italian surname, to represent colonizer cultures. Individual Native cultures have their own traditional sciences, which are diverse and should not be grouped together as “Native American.”

Is science the only way?

Ways of knowing are not universal. Folk science exists within all communities and is a valuable part of culture. Depending on cultural beliefs, the philosophical interpretation of folk science will differ. My criticism in this post is not meant to suggest that what I call American folk science should be done away with entirely. Instead, my goal is to point out specific ways in which it is limiting and can even be indirectly harmful. The mainstream scientific perspective, too, is limiting in certain ways and can certainly cause harm. I personally advocate for a pluralistic view of epistemology. The abstract concept of truth may not even be coherent, but in any case we need not concern ourselves with it from a practical perspective. If scientific realism is true, then there is no way to tell. What we observe, and what scientific practice actually does, is a consistency with our experience of reality. Many things beyond science are consistent with our experience of reality.