Homo sapiens is the only species known to have developed language. Many other animals have the ability to communicate, especially through vocalization but also through visual displays, pheromones, etc. Human language is thought to have originated from more basic vocalizations. However, no animal aside from humans uses anything quite like written language. Like most technology, writing is a very recent invention for humans. The earliest evidence of proto-writing dates back less than 10,000 years to the Neolithic period– the end of the Stone Age and the beginning of the Agricultural Revolution. This early evidence appears in the Fertile Crescent region (Mesopotamia). By this time, Homo sapiens had already spread out across a large part of the world, so humans in different places developed or acquired writing at different times.

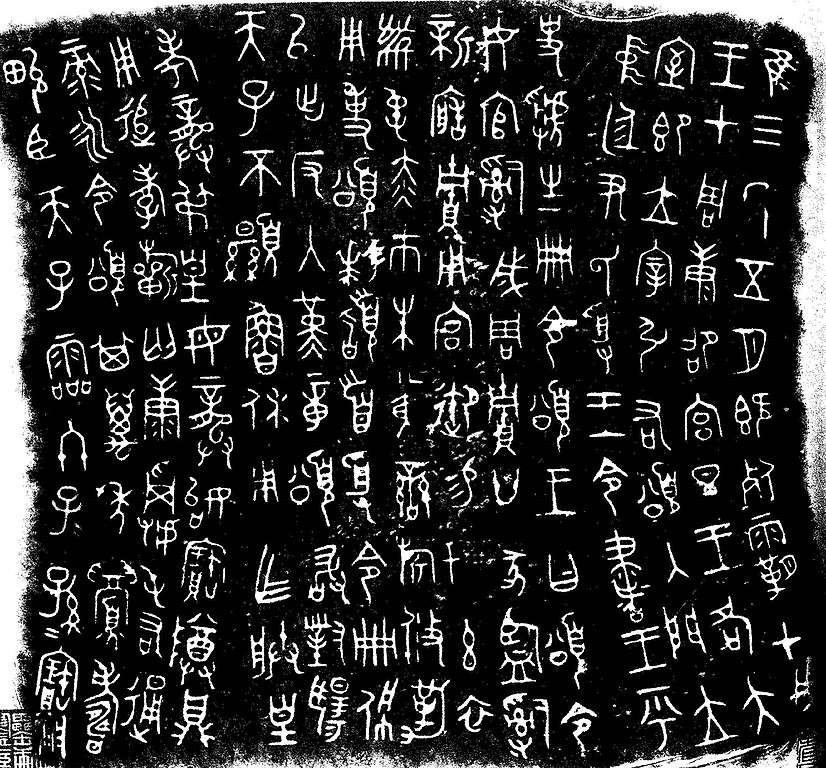

The available evidence shows that writing arose autochthonously in three places of the world: in Mesopotamia about 3200 BCE, in China about 1250 BCE, and in Mesoamerica around 650 BCE.

Schmandt-Besserat and Erard, 2007, p. 8

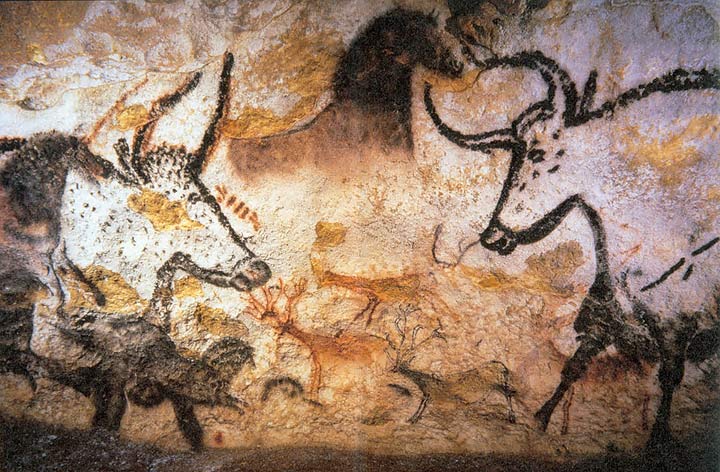

The origin of writing is generally thought to be associated with the origin and development of art. The earliest geometric designs that might be considered proto-art precede known Homo sapiens remains by hundreds of thousands of years. A major turning point was the development of representational art, depictions of people, animals, places, and events. The extent to which any of these depictions was symbolic beyond simply representing an object visually is unknown. Some of the paintings of animals could have been directions to good hunting grounds or some way of venerating animal spirits, but there is little evidence available outside the paintings themselves. Due to this lack of evidence, it’s unclear how early in our evolution humans started using drawings or figures to communicate ideas.

One way to illustrate long time scales and the relative recency of the development of writing is by compressing time scales to something that is easier to think about. A common definition of “human” is any member of genus Homo, with the term “anatomically modern human” referring to Homo sapiens exclusively. Genus Homo originated around 2.5 million years ago (MYA). If we imagine 2.5 MYA to be 12 AM on January 1st of a calendar year, with the present day being midnight on December 31st of the same year, we can place events at their relative dates on the calendar.

Regarding the development of oral language, there is no direct evidence available and indirect evidence is sparse. There is disagreement among scholars about when true language first arose. Genetics, fossils, and artifacts suggest that early Homo possessed sophisticated animal communication at minimum, and possibly already proto-language. Our most recent non-Homo sapiens relatives likely had a form of communication that resembled modern language in many ways. (Hillert, 2015). For context, stone toolmaking originated with the earliest members of Homo.

Asynchronous communication, long distance communication, and memory

When we observe animal communication, one common feature always seems to be present. Namely, the sender and recipient of a message are in close proximity in space and time. As humans developed more complex social and economic structures, there came a greater need to keep track of information over longer periods of time and to carry information over longer distances. Prior to writing, oral traditions relied on memorization. Couriers could memorize messages and relay them across long distances. However, memory is fundamentally error-prone and limited, and this was an issue recognized by ancient humans.

His speech was substantial, and its contents extensive. The messenger, whose mouth was heavy, was not able to repeat it. Because the messenger, whose mouth was tired, was not able to repeat it, the lord of Kulaba patted some clay and wrote the message as if on a tablet. Formerly, the writing of messages on clay was not established. Now, under that sun and on that day, it was indeed so. The lord of Kulaba inscribed the message like a tablet.

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, Sumerian epic poem, c. 2000 BCE from The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

The Sumerian mythical account of the invention of writing is not too far off from how it actually happened. However, the development was gradual, and there were intermediate stages before an entire message could be inscribed and read.

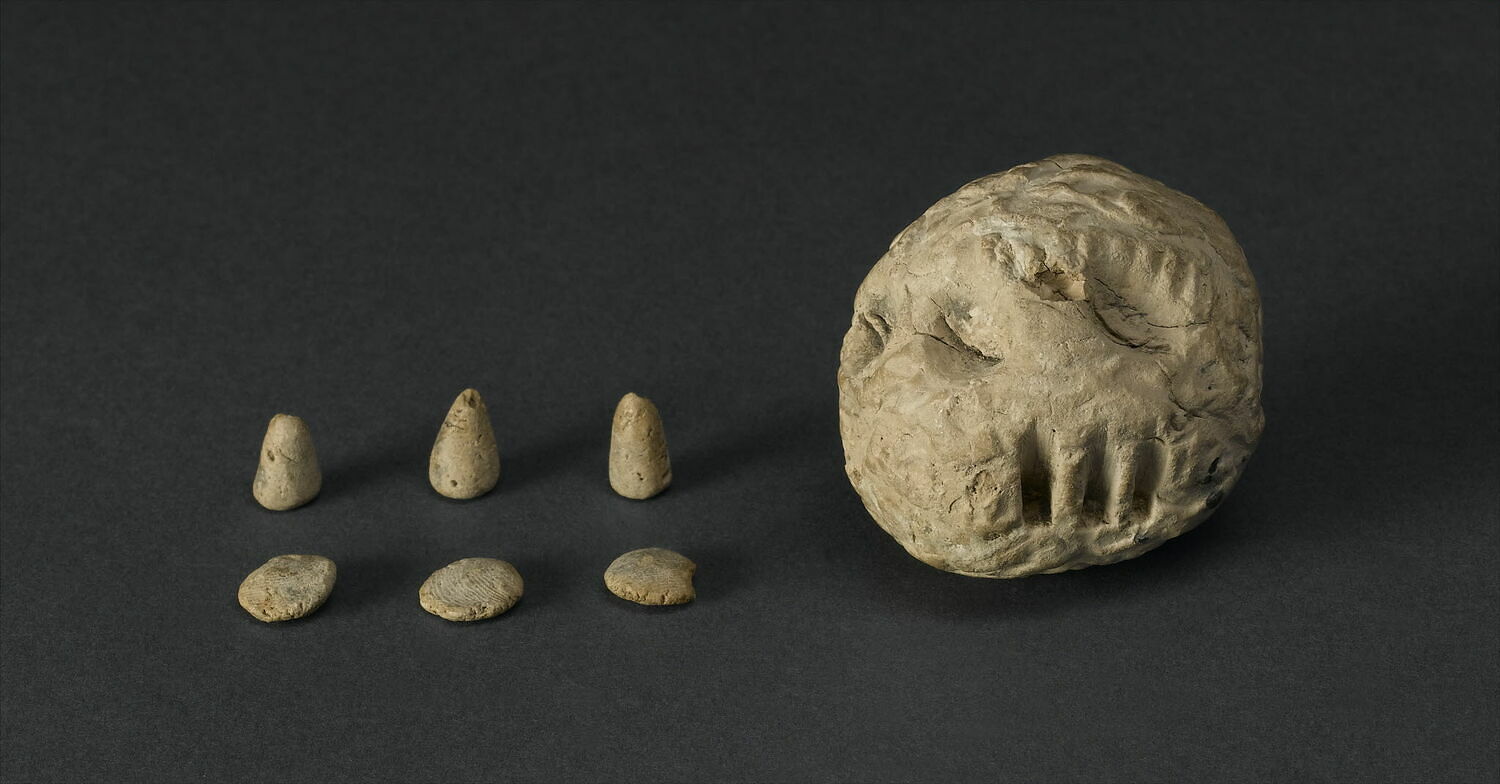

Early evidence of proto-writing in Mesopotamia is related to trade, record keeping, and mathematics. Small clay tokens were created c. 7000 BCE to represent standard quantities of goods that might need to be traded, stored, or distributed. This included cereals, jars of oil, and animals. These tokens appear to be abstract symbols; that is, they do not physically resemble the thing they represent. This is the first known use of representational symbols for a utilitarian purpose. Tokens like these continued to be used in Mesopotamia for around 4000 years. (Schmandt-Besserat and Erard, 2007.)

After tokens came into use, the next development was clay “envelopes” or bullae which prevented tampering with the quantity of tokens. The envelopes could also have tokens pressed into them to make impressions indicating their contents.

Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités orientales, SB 1940 – https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010175973 – https://collections.louvre.fr/CGU

In other cultures, there were some similar and some different ways of recording information. Ancient China used analogues of the Mesopotamian tokens. Andean cultures of South America are well know for their use of quipu (or khipu), or collections of knotted strings, to record and communicate information prior to their use of written language (the tradition continued after that point as well). Ancient Chinese and Pacific Islander cultures are thought to have independently developed a similar system of tying knots to record information.

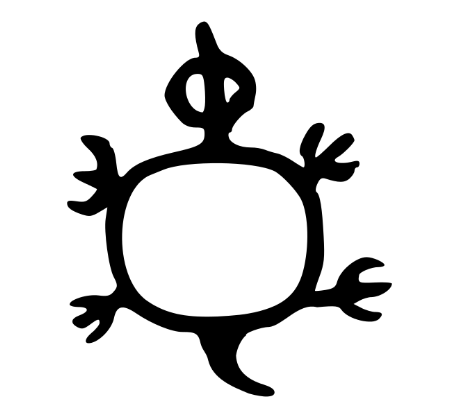

Pictograms

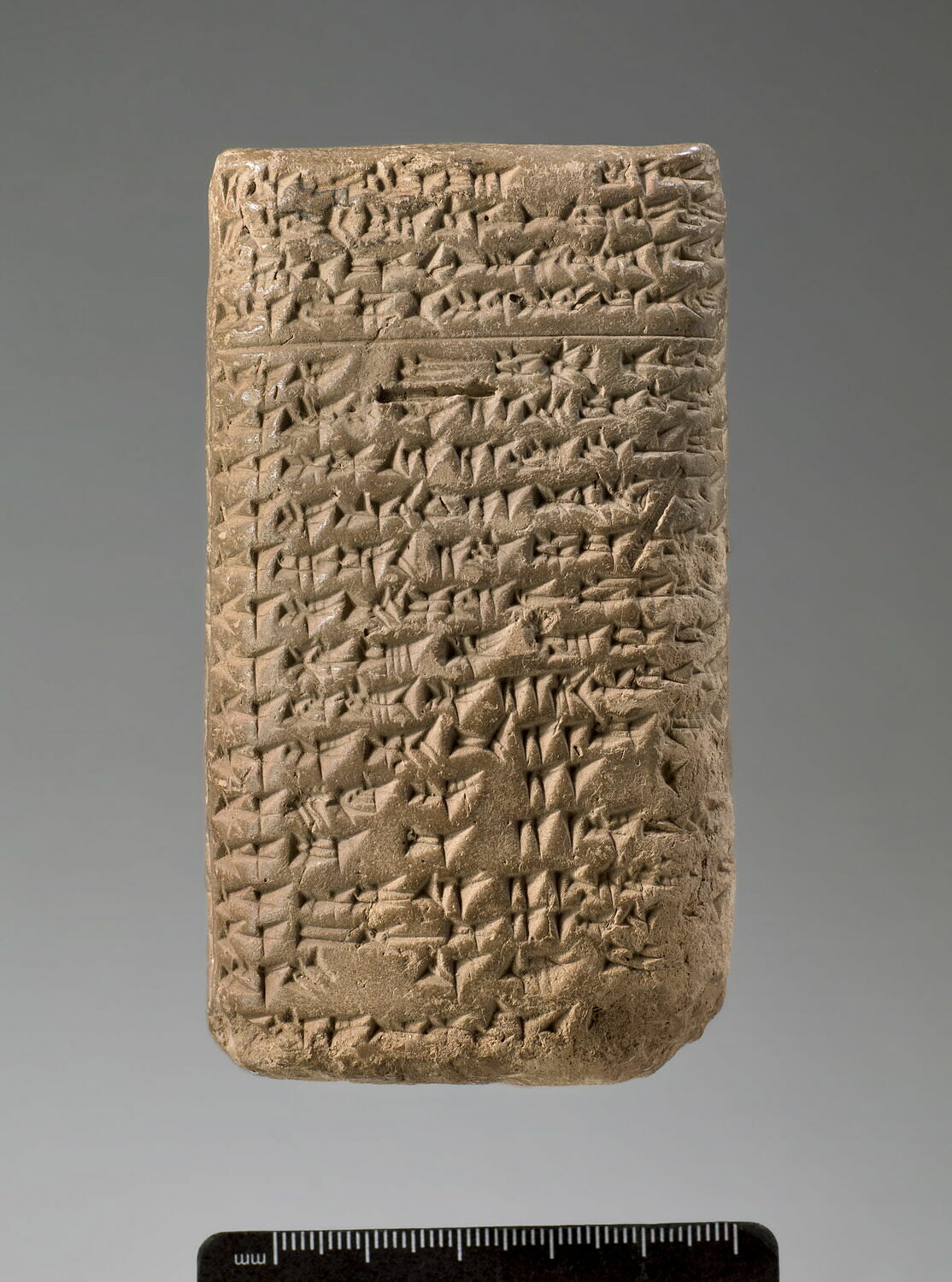

Dealing with large quantities of tokens is impractical, and people of ancient Mesopotamia had a need to record other types of information. For example, one of the earliest types of non-economic records describes the accomplishments of kings. For these purposes, making impressions on a clay tablet with a stylus was the solution. In proto-linguistic cultures, information was frequently recorded using pictograms: symbols that visually resemble the things they represent. Pictograms are still used in many applications today to communicate information quickly or in a way that is not language-specific.

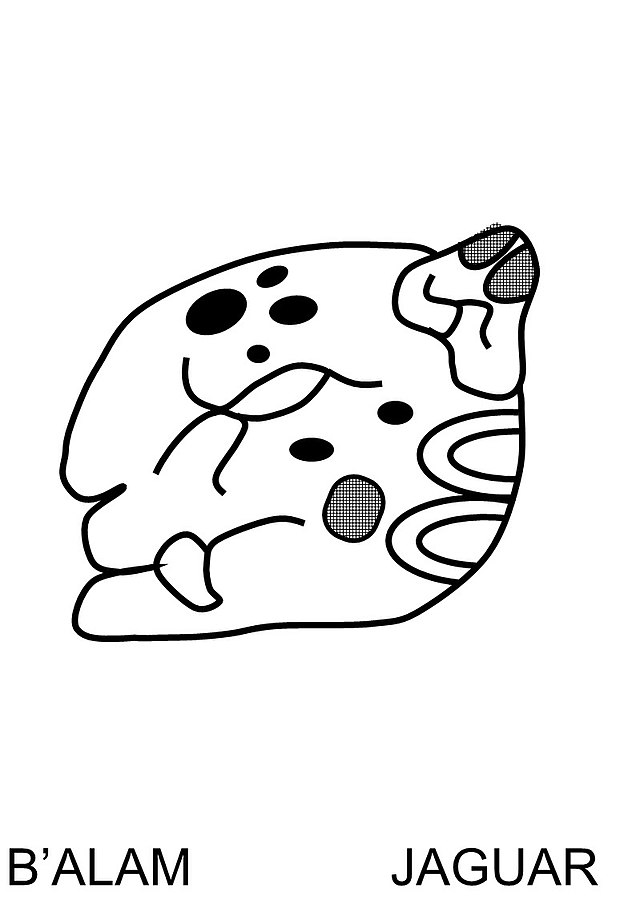

An important distinction between a pictogram and a truly linguistic symbol (such as a written word) is that a pictogram means something, but it does not say something. It would not make sense to “read a pictogram out loud,” but you could verbally explain the meaning of the pictogram.

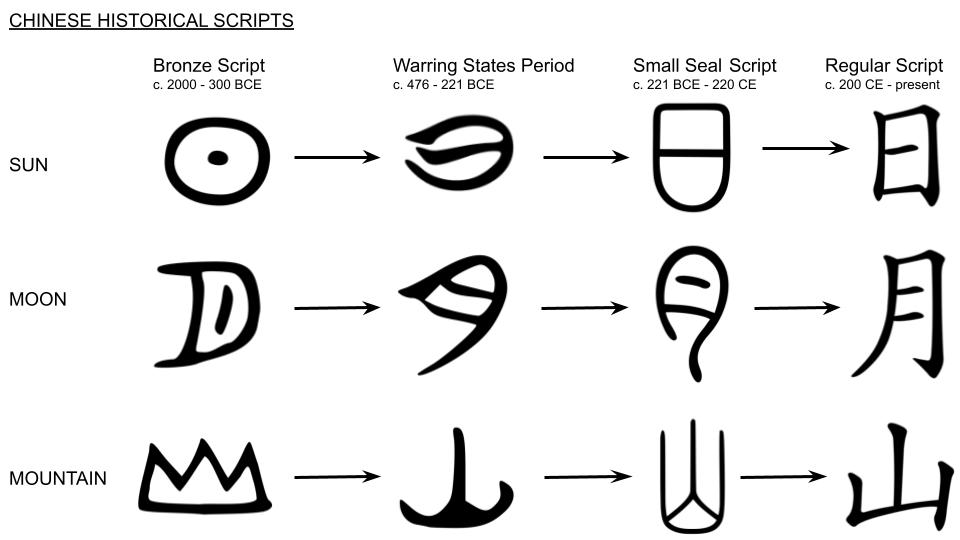

In the cultures that are known to have developed writing independently, pictograms appear to always be one of the first steps towards written language. As a result, glyphs of the subsequent written language tend to originate from pictograms.

The first recorded human speech

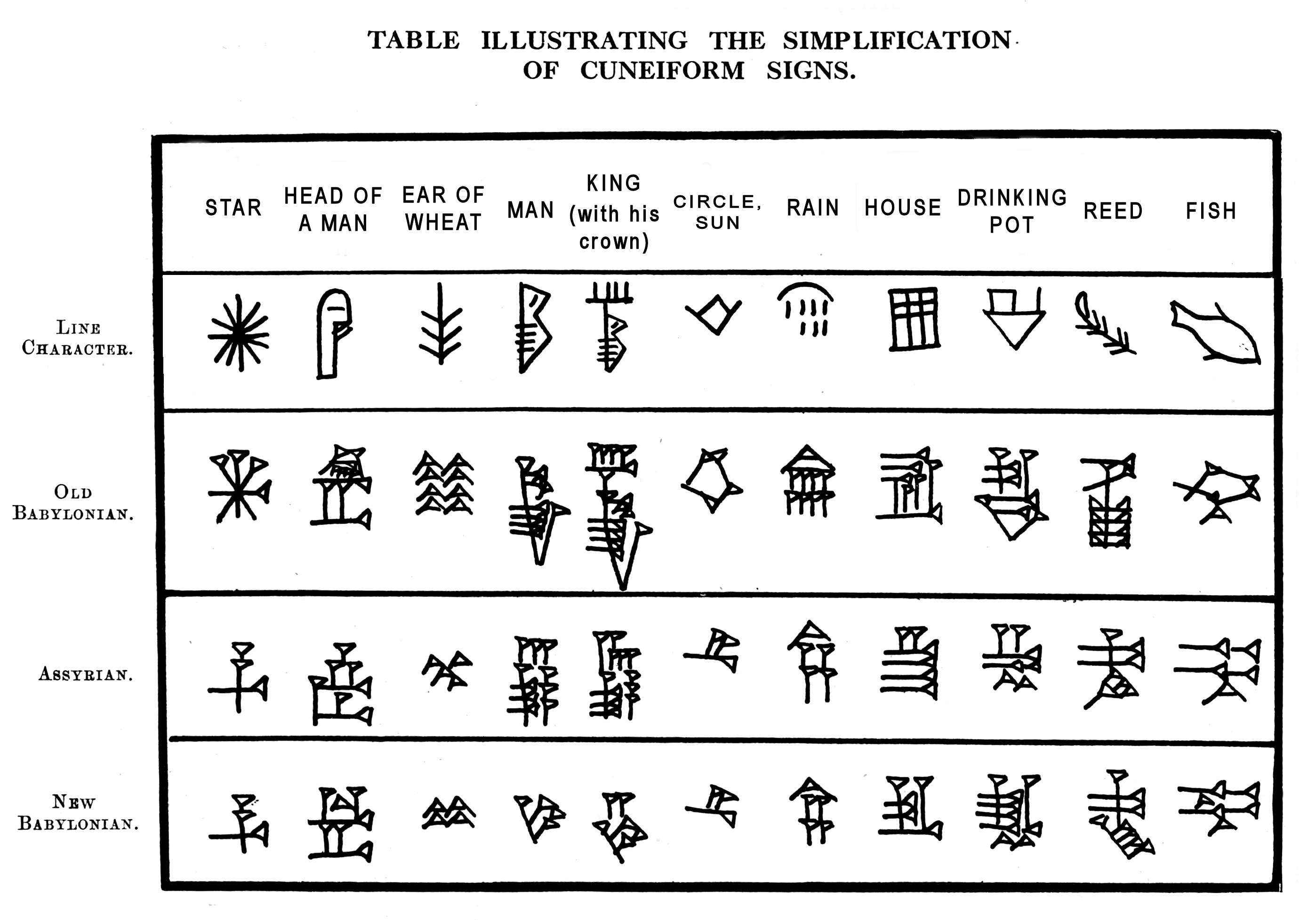

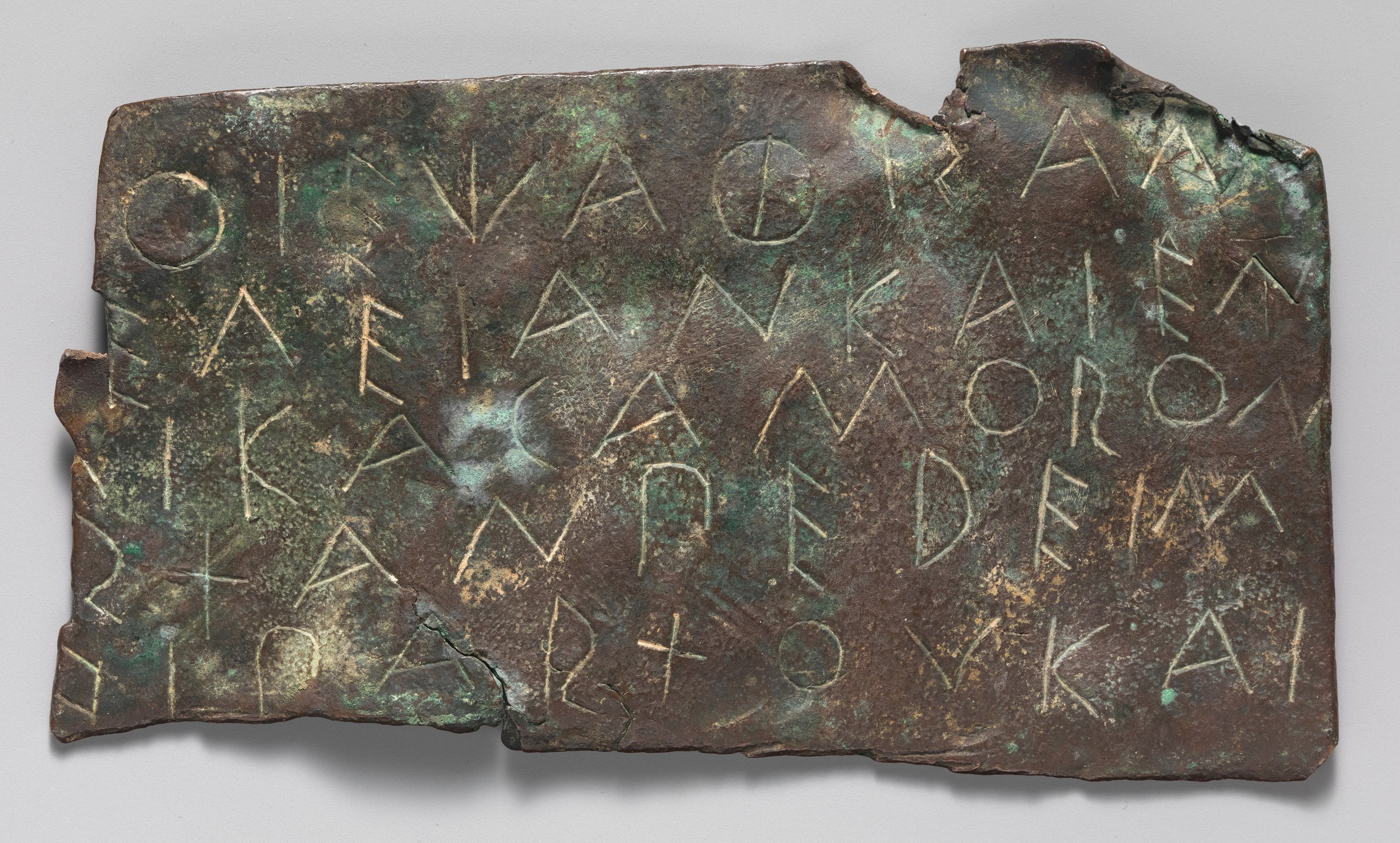

A major turning point in this story is the transition from mere pictograms to ideograms (representing abstract ideas), logograms (representing words), and phonograms (representing sounds). As this transition happened, it became less important for the glyphs themselves to resemble something specific. Instead, ease of writing and ease of reading arose as priorities, which resulted in a gradual change in symbol shape over time. In Mesopotamia, a significant change came with the adoption of a pointed stylus used to make wedge-shaped (cunei-form) impressions in clay tablets. The typical writing medium has a great effect on how a writing system develops: whether it be impressed upon clay, carved in stone, or painted with a brush.

Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités orientales, AO 2221 – https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010123702 – https://collections.louvre.fr/CGU

See Postgate, Wang & Wilkinson (1995), Schmandt-Besserat and Erard (2007), and Woods (2020).

Language is what happens when people make do with the linguistic assets they have available (and the consequences of this principle)

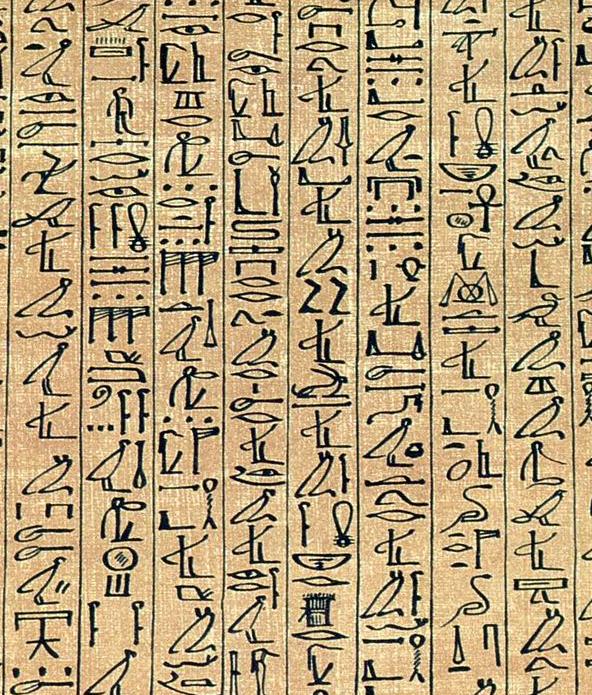

Egyptian is an illustrative example. Writing is thought to have emerged in Egypt independently and around the same time as Mesopotamia, although there may have been some early contact between these cultures. Like other cultures, Egyptians used pictograms early on. As they developed a full blown writing system, the ancient Egyptians placed increasingly complex symbolic demands on their glyphs.

Consider the ancient Egyptian word for vulture, usually transliterated “a.” This word is written with a single hieroglyph, a pictogram of a vulture. The noun “vulture” is a homophone for the verb “to tread” in ancient Egyptian, so they get written with the same hieroglyph. This is called the rebus principle. An example of a rebus in English is IOU, since we get the meaning from how it’s spoken aloud and not from how it’s written. In order to distinguish between the two words “vulture” and “to tread,” the latter is spelled with an additional hieroglyph called a determinative. This hieroglyph does not affect pronunciation, but indicates what the word is related to or what category it falls under. The vulture hieroglyph also gets used as a pure phonogram for the “a” sound in other words. When combined with a hieroglyph of a papyrus plant which acts as a phonogram, we can spell multiple words pronounced “ha.” Without a determinative this is the preposition “behind,” with a determinative for head it is the noun “back of the head,” and with a determinative for activities involving ideas, it’s the particle “if only.”

A hieroglyph could be “used for its phonetic value, for the image it portrays, or for a combination of both functions … The hieroglyphic writing system could be highly efficient … blurring the line between phonetic writing and picture writing” (Johnson, 2010, p. 152).

A single hieroglyph could represent a single consonant, two consonants, or three consonants (most vowels had to be inferred). Aside from determinatives, some hieroglyphs had grammatical uses, such as a suffix to indicate possession. With this highly sophisticated system, it can be surprising in retrospect that it was once uncertain whether hieroglyphics constituted a true writing system at all.

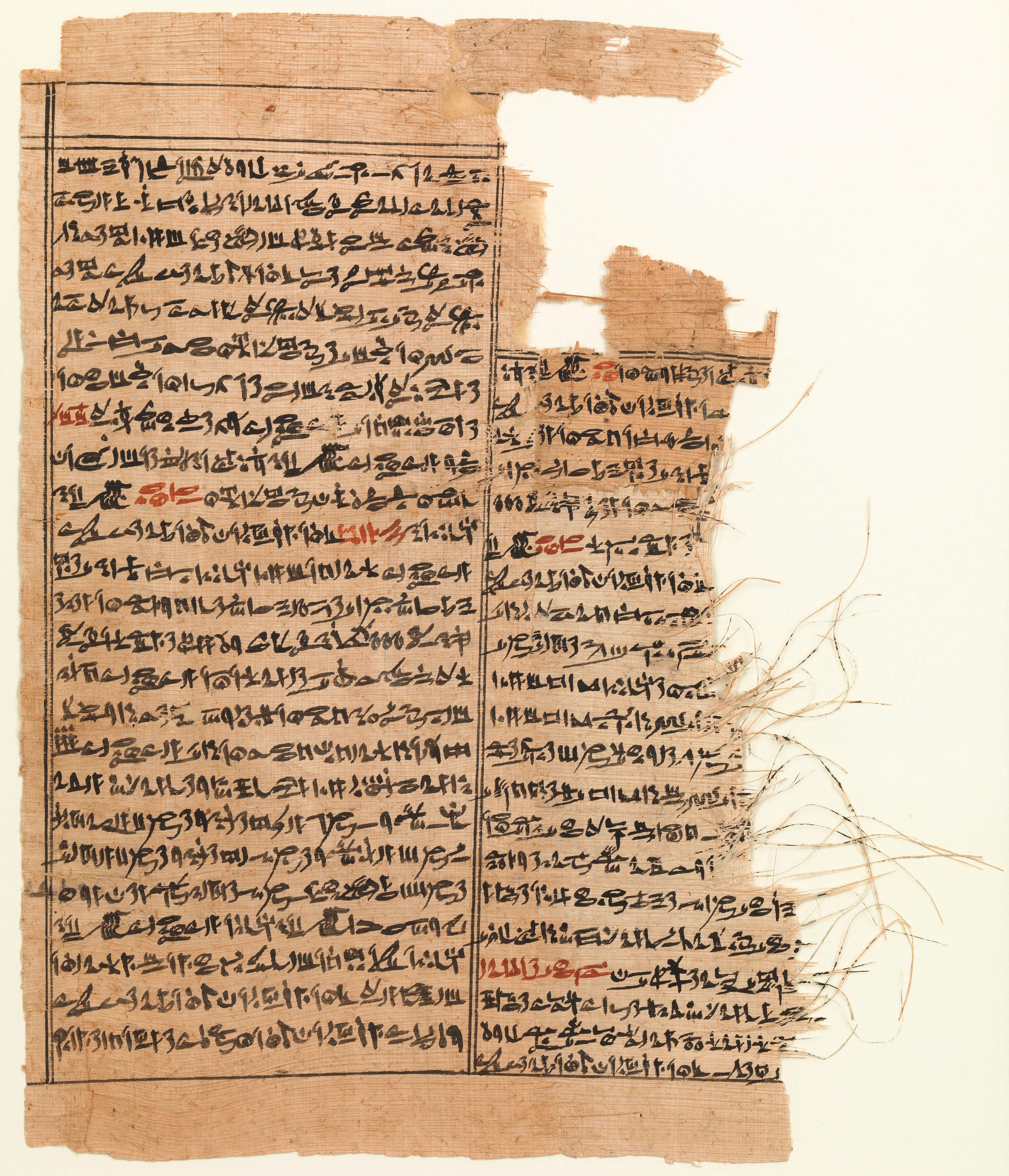

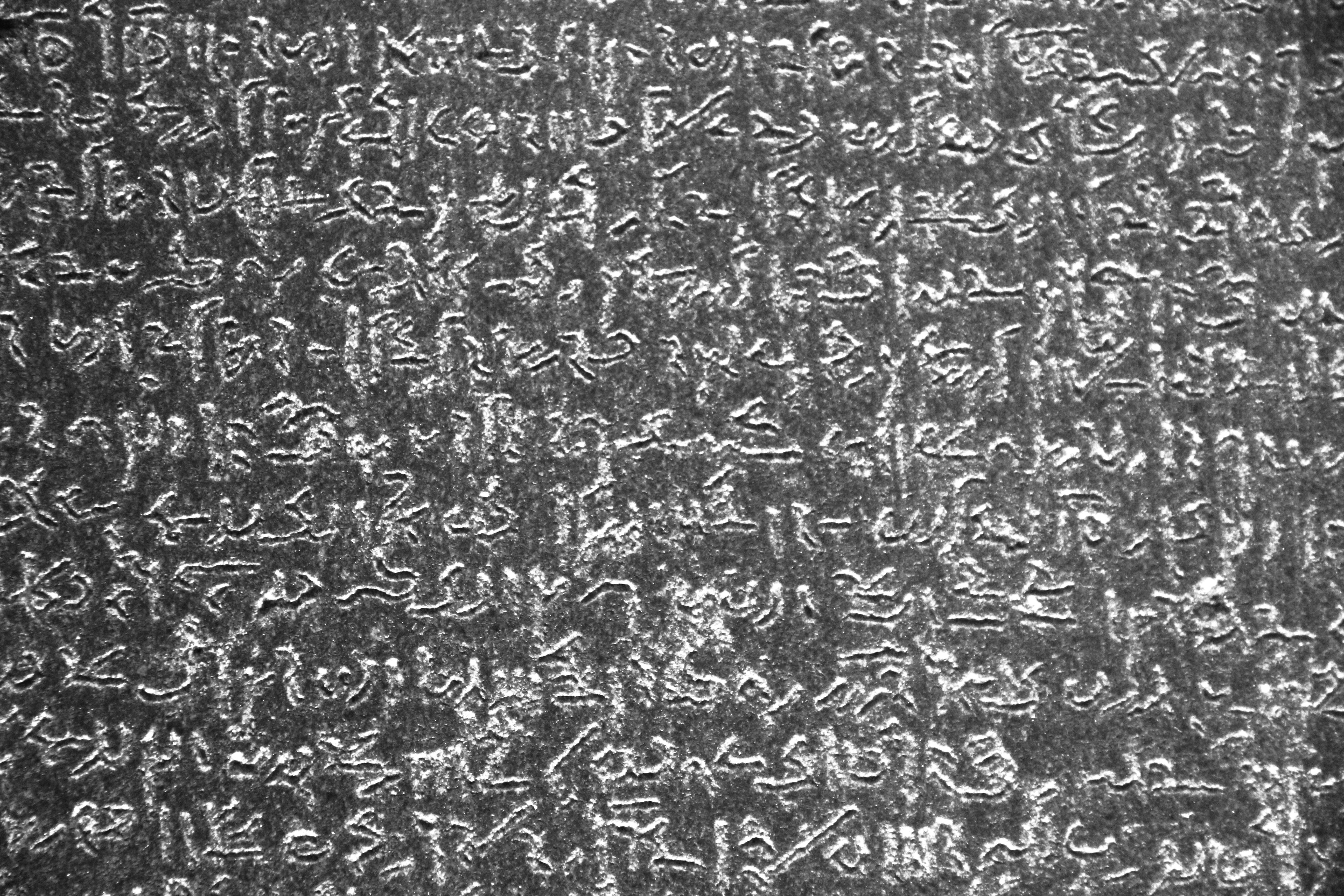

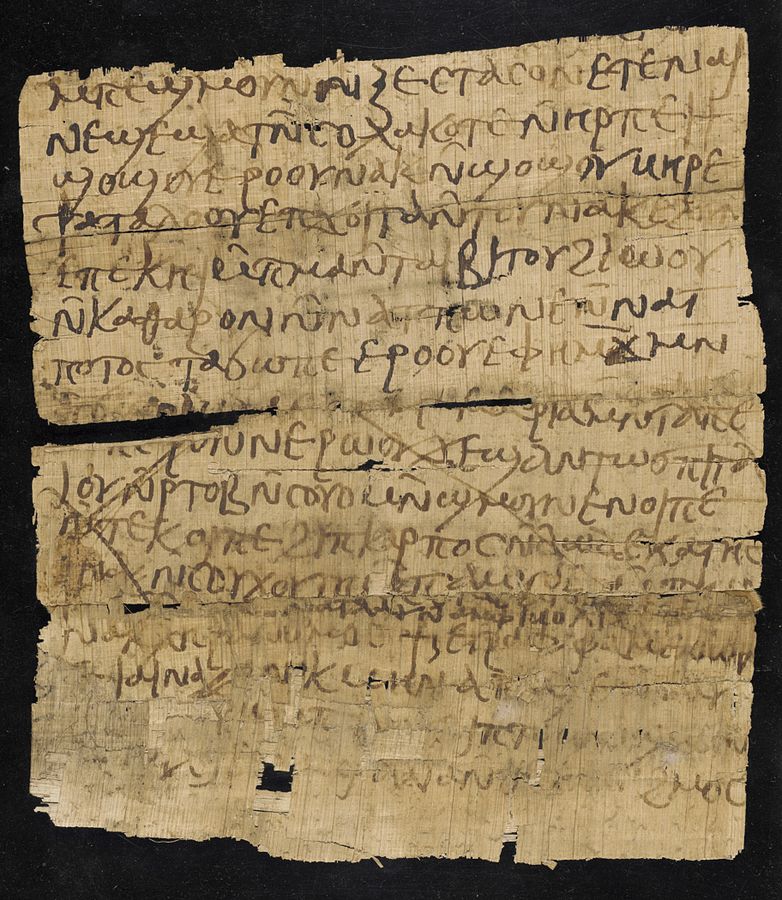

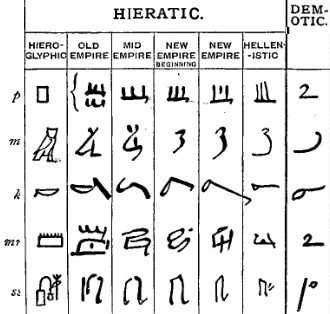

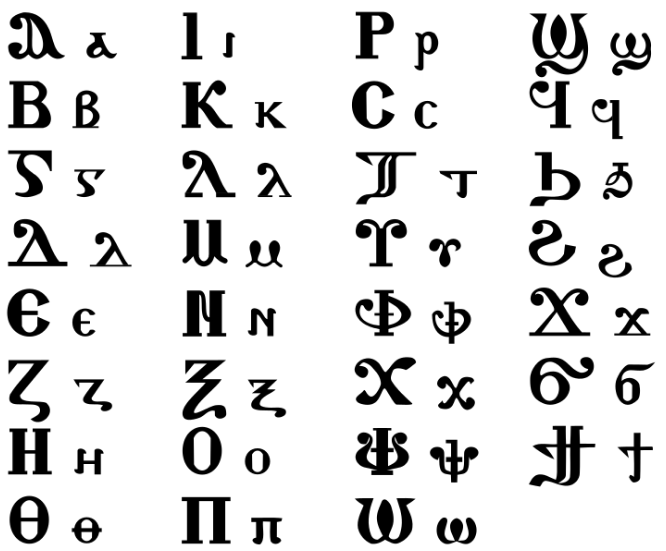

Hieroglyphics were used in ceremonial contexts for thousands of years, especially in stone inscriptions. However, ancient Egyptian scribes recognized a need for faster, easier writing systems for everyday use. This led to the development of hieratic script, a cursive script based loosely on hieroglyphics. (A second type of handwritten script that was sometimes used, simply called cursive hieroglyphics, more closely resembles the original pictograms.) Hieratic evolved over time into another script called demotic. So in 196 BCE, when the Rosetta Stone was created, the ancient Egyptians inscribed it with both hieroglyphics and demotic, since both systems were still being used. As a result, the Rosetta Stone did not just have ancient Egyptian and ancient Greek on it, but rather it had the ancient Egyptian on it twice. The same spoken language had two different writing systems, representing the same words and sounds in different ways. It was this, along with the Greek translation, that was the key to deciphering the ancient Egyptian language. If the Rosetta Stone had contained only hieroglyphics and Greek, it might never have been deciphered. Another source of information scholars used to reconstruct ancient Egyptian is Coptic. After Egypt was conquered by Rome, it became more culturally connected to the Mediterranean. Egyptians began writing their language in a modified version of the Greek alphabet (spelling out the words phonetically, adding letters for sounds that didn’t exist in Greek). The ancient Egyptian language, written in this script, came to be known as Coptic. Coptic was the primary language used in Egypt until it was supplanted by Arabic. Today, there are no native speakers of Coptic, but it is still used in Coptic Christian churches.

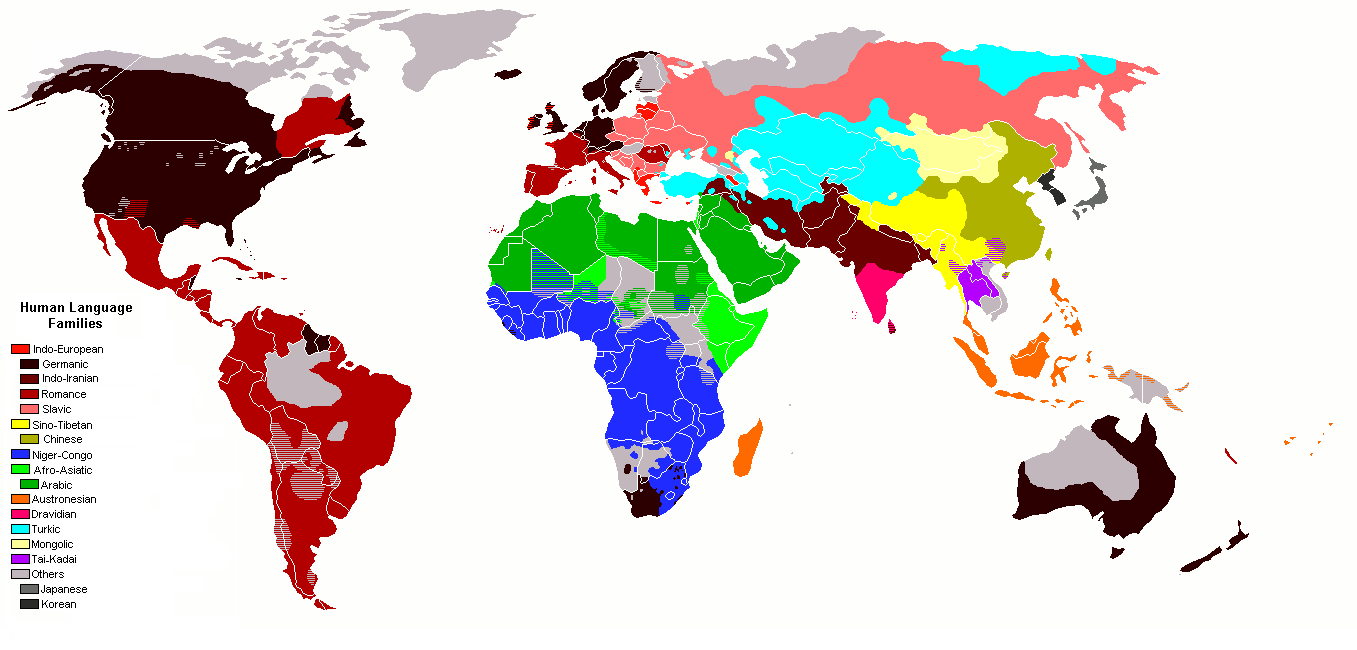

The story of the Egyptian language is one that involves natural change over time (such as the transition from Old Egyptian to Late Egyptian hieroglyphs) but also intentional decisions on the part of ancient Egyptian scribes to use specific writing systems in specific contexts, and later to use Greek letters to form the Coptic alphabet. At any given point in history, they used what was available to them to accomplish what they needed language to accomplish, be it record keeping, ceremonial, etc. More generally, this is what all language users do. However, cultures differ in what resources they have, what needs they have, how exactly they use their resources to satisfy their needs, and how interactions with different cultures affect them, resulting in the linguistic diversity that we see in the world today.

The ancient Mesopotamian cultural exchange and beyond

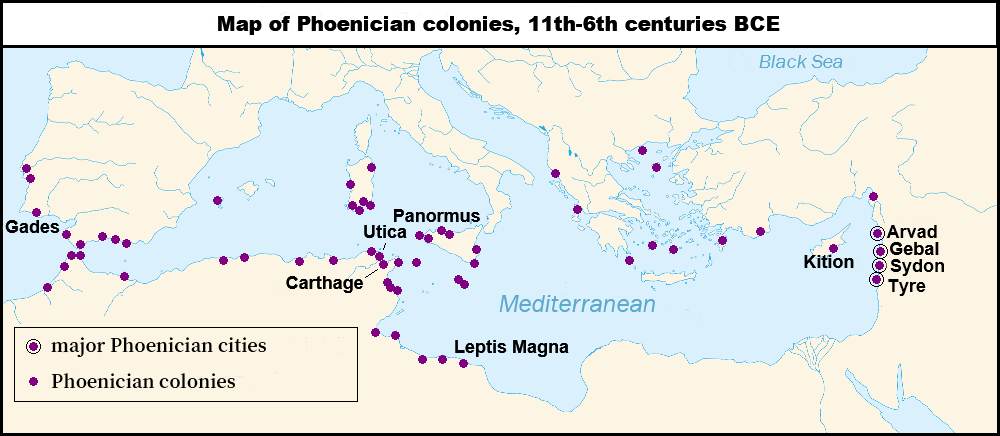

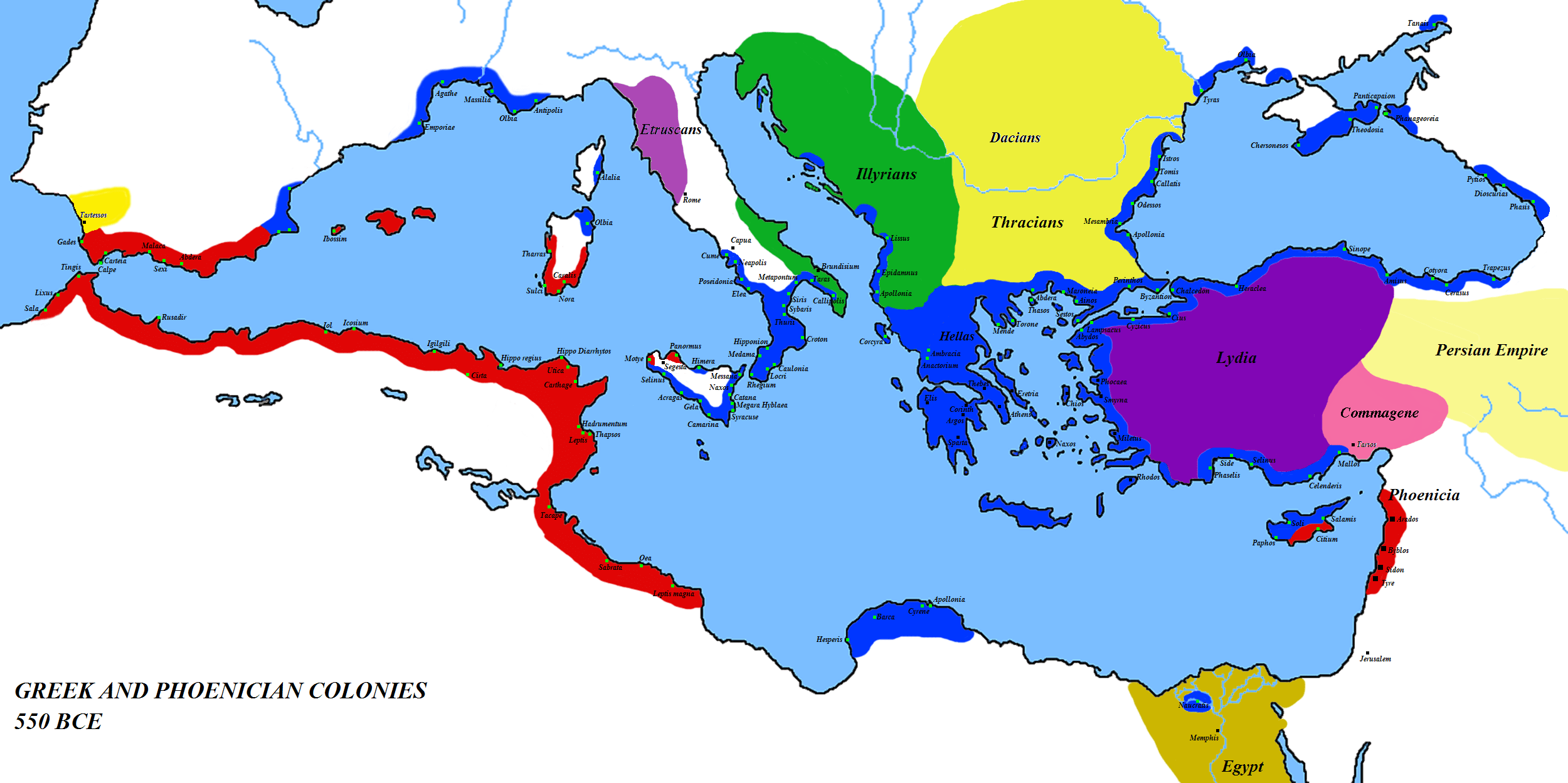

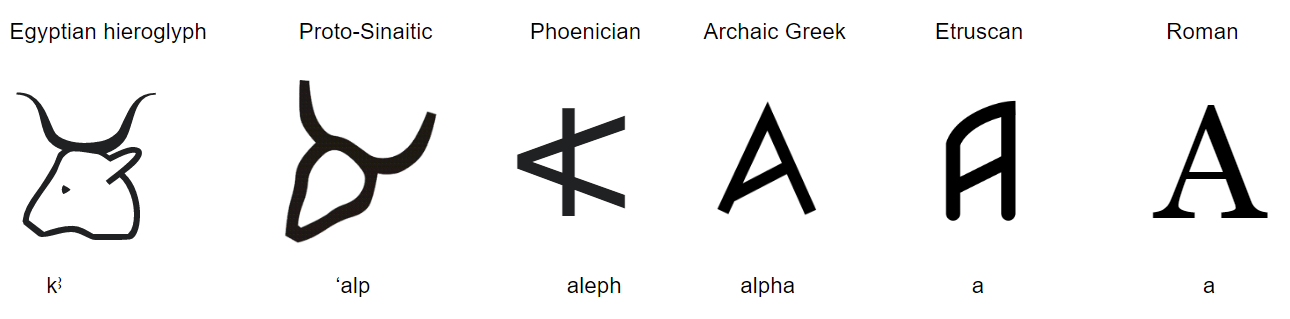

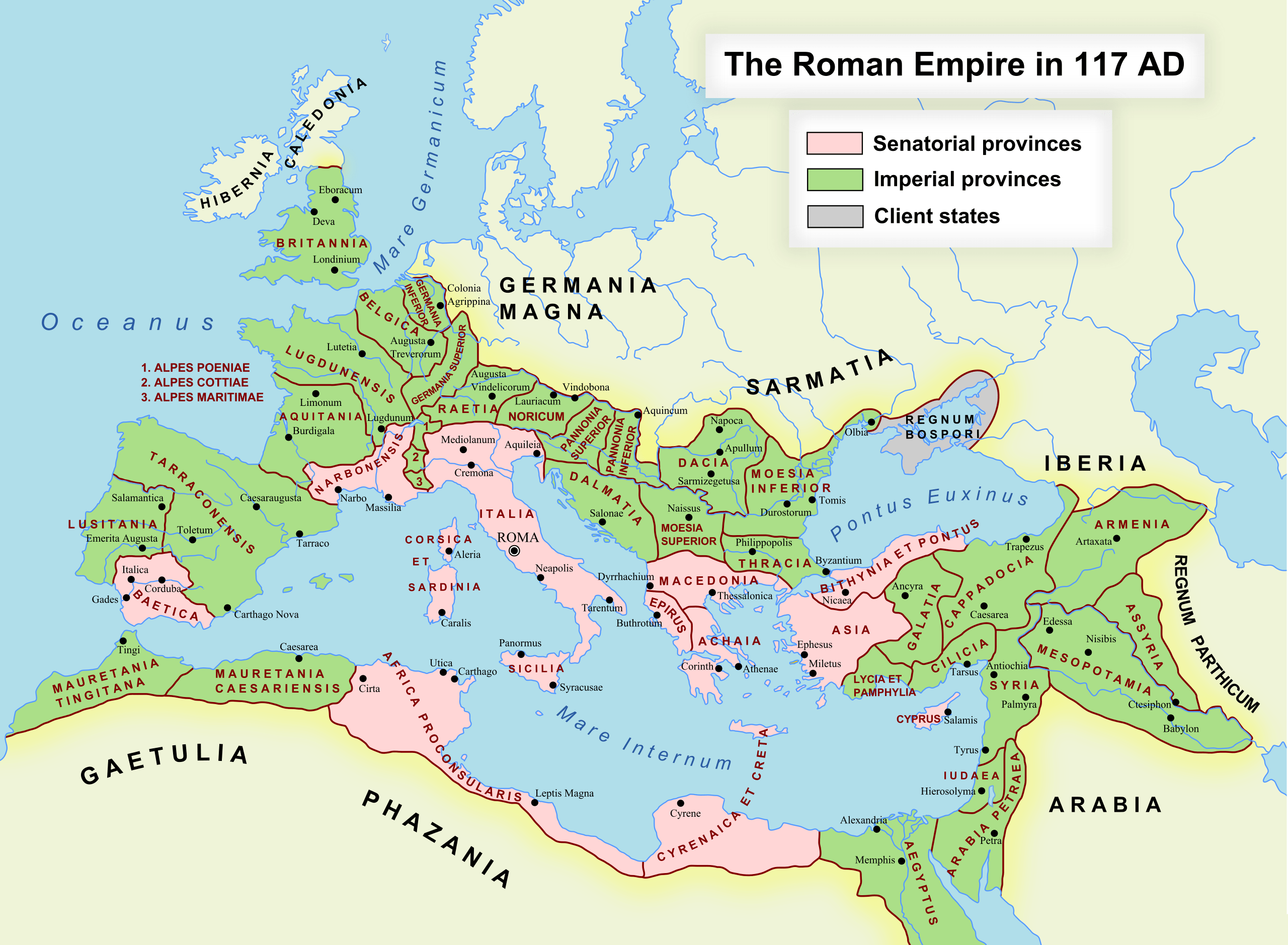

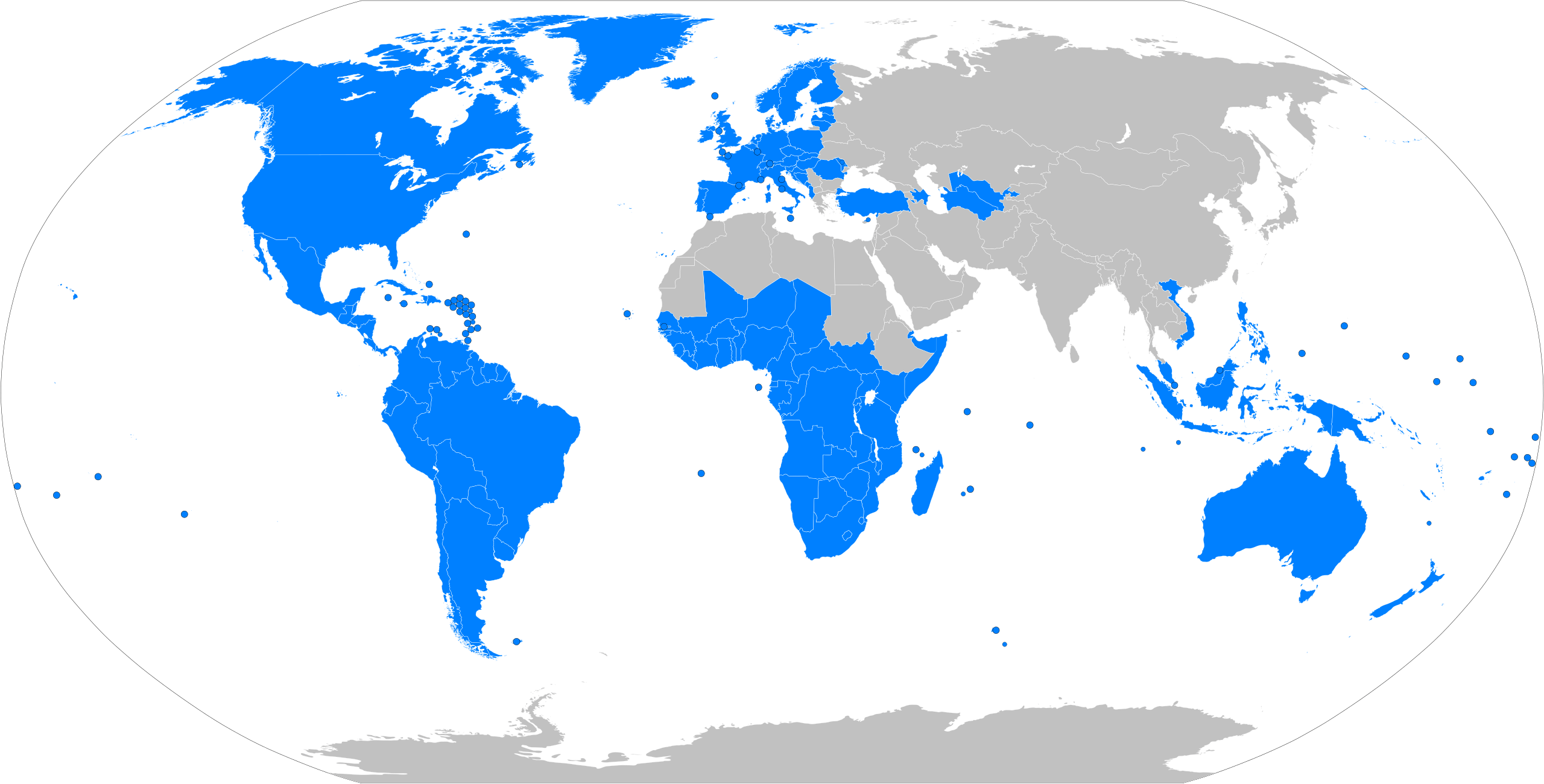

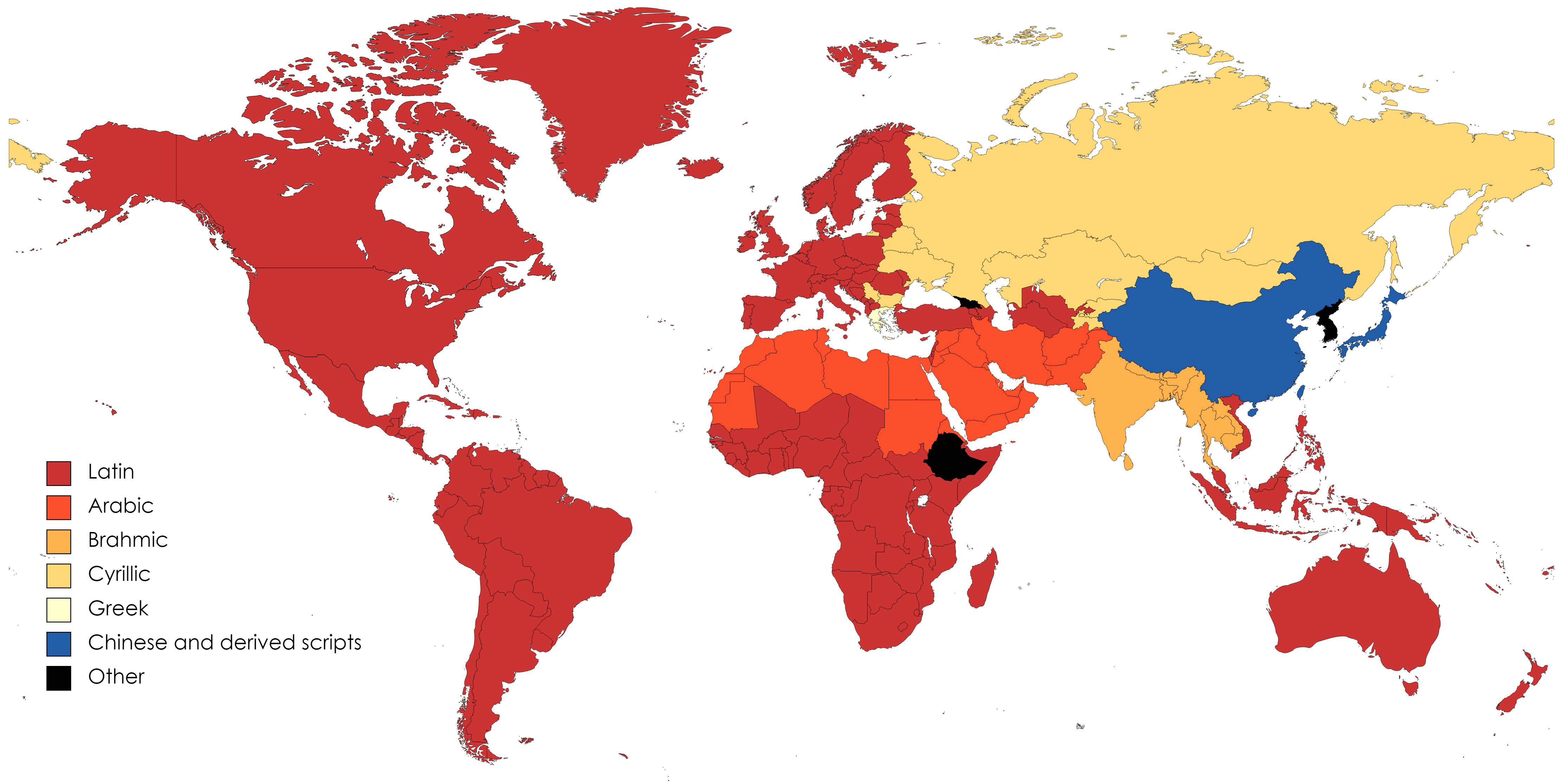

The ancient people of the Levant (or eastern Mediterranean region) are thought to have been influenced by Egypt. This group of people spoke an early Semitic language, and are believed to have adopted Egyptian hieroglyphs to represent sounds in their language. For example, the Western Semitic word for ox is ‘alp, so the hieroglyph of an ox head was adopted as the phonogram for the initial sound of this word. This proposed Proto-Sinaitic script developed into the Phoenician alphabet. The Phoenicians engaged in trade with people to the east and south, and sailed extensively throughout the eastern and southern Mediterranean. The Phoenician alphabet influenced the writing systems of Hebrew, Arabic, and Greek. Greek colonies on the Italian peninsula are thought to have brought the alphabet to the Etruscan civilization, which in turn resulted in the development of the roman alphabet. The roman alphabet, of course, became widespread in Europe because of the Roman Empire. It was spread further throughout the world by European colonial powers over the last 500 years. Now, even such languages as Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia) use the roman alphabet.

See Lam (2010).

The Phoenician alphabet also spread east across land, developing through Aramaic into the alphabets of Hebrew, Arabic, and Sanskrit (and later, through Greek, into the Cyrillic alphabet). These scripts diversified and spread across North Africa and Asia. Now, the vast majority of literate people use one of two writing systems: a more-or-less phonetic alphabet derived originally from Phoenician, or a system based on Chinese logographic characters. There are a few notable exceptions.

One thing that I find remarkable is that the diversity of spoken languages doesn’t line up completely with the diversity of written languages. In particular, there seem to be many examples of languages that are not closely related using the same or closely related scripts. This may be related to the fact that, historically, literacy has been associated with government and religion. Colonization and proselytization tend to spread written language in a top-down way, while spoken language tends to spread through migration and cultural exchange in a more grassroots fashion.

What about the exceptions?

There are many writing systems that are unrelated to both Phoenician and Chinese (or no direct connection is known). Most of these are used by small language communities, however there are a few cases in which such a script is the official or dominant writing system within a country. Three examples of this are Georgia, Korea, and Ethiopia.

![Sign in Ethiopian Ge'ez and English that reads, "Welcome," and "Kibran st. Gabrael [sic] Unity of Monastery."](https://hawesthoughts.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/et_amhara_asv2018-02_img099_lake_tana_at_bahir_dar.jpg?w=1172)

Georgia

The country of Georgia is linguistically isolated. The Georgian language is a member of the Kartvelian language family, meaning it is not closely related to any languages outside the southern Caucasus mountains. The writing system for Georgian consists of three different scripts, called Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. These are three alphabets that have essentially the same letters but are written differently. Mkhedruli is the standard script for Georgian and other (considerably smaller) Kartvelian languages, while the other two scripts are mostly used by the Georgian Orthodox Church. The origins of this writing system are unknown, but the earliest examples of it appear in the 5th century CE.

Korea

The Korean language is isolated as well, being the only major language in the Koreanic language family. Korean is not closely related to Chinese nor Japanese. The earliest writing system for Korean was Hanja, Chinese characters adapted for use in Korean. The Korean phonetic alphabetic, Hangul, was invented in 1443 CE by King Sejong the Great to promote literacy. While Chinese characters may have inspired certain aspects of Hangul, its symbols were not derived directly from Chinese characters.

Ethiopia

Like many African countries, Ethiopia is highly linguistically diverse. Major languages spoken in Ethiopia include Oromo, Amharic, Somali, Tigrinya, Afar, and Sidamo. These are mostly regional indigenous languages. Due to influence from Europe and the Middle East, Ethiopia also has some English speakers and Arabic speakers. As a result, some Ethiopian languages are written using the roman or Arabic alphabets. However, the primary script for native Ethiopian languages is Ge’ez, which is an abugida (an alphabet-like system in which only consonants are written). Ge’ez was originally the writing system for the Ge’ez language, and like English and Arabic, the script was originally derived from Egyptian hieroglyphics. However, Ge’ez did not develop from Phoenician, making it very different from the roman and Arabic alphabets.

Timeline of writing developments

BCE 8500 Simple tokens in the Middle East 3500 Complex tokens and clay envelopes 3300-3200 Earliest writing in Mesopotamia and Egypt 3200-3000 Egyptian hieratic script 2500 Adaptation of cuneiform to write Semitic languages in Mesopotamia and Syria 1850 Proto-Sinaitic alphabetic texts 1650 Hittite cuneiform 1600 Earliest Proto-Canaanite alphabetic inscription 1200 Oracle-bone inscriptions, China 1200-600 Development of Olmec writing 1000 Phoenician alphabet 900-600 Old Aramaic inscriptions 800 First Greek inscriptions 800 South Arabian script 700 Earliest Latin script 650 Egyptian Demotic script 600-200 Zapotec writing 500 Persian Achaemenid Empire at its greatest extent 400-200 Earliest Maya writing 400 The Tao Te Ching written by Laozi 250 Jewish square script, used for Hebrew and Aramaic 250 Maurya Empire of India at its greatest extent 100 Spread of Maya writing CE 2 Han Empire of China at its greatest extent 75 Last dated Assyro-Babylonian cuneiform text 105 Traditional date for the invention of paper in China (probably invented one to two centuries earlier) 117 Roman Empire at its greatest extent 200 Chinese regular script in virtually modern form 200-300 Coptic script appears 394 Last dated hieroglyphic inscription 452 Last dated Egyptian Demotic graffito 600-800 Late Classic Maya writing 800-1258 Islamic Golden Age, translation of ancient texts into Arabic, spread of literacy 1300 Greatest extent of the Mongol Empire 1440 Gutenberg movable-type printing press invented in Germany 1492 Beginning of European colonization of the Americas Adapted from Woods, 2010, p. 13. All dates are approximate.

References

Hillert, D. G. (2015). On the Evolving Biology of Language. Frontiers in Psychology, 6.

Johnson, J. H. (2010). Egyptian Hieroglyphic Writing. In Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. C. Woods, Ed., pp. 149-152. Oriental Institute Museum Publications No. 32. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Joordens, J. C. A. et al. (2014). Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving. Nature, 518(7538), pp. 228–231.

Lam, J. (2010). Invention and Development of the Alphabet. In Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. C. Woods, Ed., pp. 189-196. Oriental Institute Museum Publications No. 32. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Postgate, N., T. Wang & T. Wilkinson. (1995). The evidence for early writing: utilitarian or ceremonial? Antiquity, 69, pp. 459-480.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. and M. Erard. (2007). Origins and Forms of Writing. In Handbook of Research on Writing. C. Bazerman, Ed., pp 7-22. Routledge.

Woods, C., Ed. (2010). Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. Oriental Institute Museum Publications No. 32. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Woods, C. (2020). The Emergence of Cuneiform Writing. In A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages, R. Hasselbach-Andee, Ed., pp. 27–46. Wiley.